By Carleigh Davis

Abstract

Purpose: The goal of this article is to understand how and why content relating to a popular nutrition program, the Whole30, is taken up or discarded when shifting between producer- and participant-controlled media.

Method: This article utilizes memetic rhetorical analysis to identify interface- and content-specific memes and to explore the connections between those memes that create environments to which some adapt successfully while other are lost.

Results: My analysis shows that the interface memes that characterize the Whole30 Facebook Community page create a communicative situation in which personal experience is more likely to be persuasive than scientific research or institutionally conferred credentials.

Conclusion: Technical communicators need to craft technical and scientific content to allow for transmediated community interaction that draws on the affordances of social media sites to maintain the integrity of information.

Keywords: memetics, social media, Facebook, nutrition, transmedia

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Examines the ways a social media site affects user interaction with and interpretation of scientific content

- Interrogates the efficacy of relying on the established credibility of expert researchers when communicating with audiences across a variety of participatory media

- Argues that the affordances of media interfaces determine the ability of scientific content to successfully spread in transmediated communities

- Articulates a need for technical and scientific sources of information to consider the transmediation of content produced for public audiences

Introduction

The Internet is home to an abundance of complex information that can be difficult for many casual users to navigate. For at least the last decade, technical communication scholars have noted that a great deal of the rhetorical work often done by paid technical communicators is being taken up by private users online as a means of social interaction. Chong (2018) studied this phenomenon relating to beauty tutorials on YouTube; van Ittersum (2014) applied this understanding to DIY instructions posted online by and for amateur hobbyists; Ding (2009) took it up regarding the use of a variety of on- and offline media to facilitate risk communication in the SARS epidemic of 2002, and other examples abound. With such vast proliferation of technical communication practices online, Kimball (2017) characterized our present era as “the golden age of technical communication” (p. 341).

Such practices are also the locus of concerns with the spread of mis/disinformation, now that mass-consumed content is not controlled exclusively by experts, and “click bait” (content that quickly attracts the attention of potential readers, often at the expense of accuracy or factual rigor, to drive traffic to the producing website) by means of social media is a viable means of content distribution. This concern can be particularly evident when readers’ health is at stake, should they take the proffered advice. Waszak, Kasprzycka-Waszak, and Kubanek (2018) explored the prevalence of this phenomenon in their study of the spread of medical fake news on social media, finding that a single source of inaccurate information can quickly dominate a social network, particularly when that content refers to health topics about which public opinions run strong (their examples refer to vaccines and HIV/AIDS). Dixon, McKeever, Holton, Clarke, & Eosco (2015) and Bode and Vraga (2015) likewise noted the difficulty that researchers and practitioners alike have with correcting misinformation once it has spread online. As such, one of the foremost challenges facing technical communicators today is the fraught task of helping online readers to identify scientifically valid and best-practice oriented content among the chaff.

From product reviews to instructions, and from testimonials to evaluative reports, social media is saturated with content representing a variety of perspectives and experiences. This is the strength of these media: The participatory work put in by community members to build knowledge on a subject of common interest affords participants with new opportunities to engage with content that matters to them. It also acts as a publicly oriented system of checks and balances to the typically privileged access required to participate in scientific discourse that is controlled by research- and product-producers.

In producer-controlled media, content is inherently controlled by entities with the means to access content distribution on a scale necessary to reach the producers’ intended audience(s), whatever these might be. Such content is more likely to be backed by well-funded studies conducted by experts in the field. Conversely, social media acts as a more democratic and interactive medium and tends to value content that is privileged by the algorithms of various social media sites (e.g., Kite, Foley, Grunseit, & Freeman, 2016). The rapid convergence of on- and offline experiences means most discourse communities that frequent Internet users belong to are transmediated—that is, defined by interaction across more than one communicative medium—by default. This confluence allows for participatory “world-making” (Jenkins, 2006, p. 294) in technical and scientific discourse through user interaction, potentially benefiting access to quality scientific content online. However, this confluence also carries the associated risk of content being contaminated by inaccurate and even harmful information that is not supported by traditional research.

Such is the case with the ever-growing body of nutrition and weight-loss communities online. Transmedia world-building of health and nutrition programs and information is extremely common as online users work to share resources in the name of health, fitness, or aesthetic. For example, loosely structured diet and nutrition groups, like those surrounding Paleo, Ketogenic/ Low-carb, and alkaline diets, as well as the Whole30, which this article will discuss in depth, appear across many websites and social media platforms. These groups are characterized not only by the ways that individual members use the unique affordances of each media platform to support and motivate one another but also by the import/export of information related to the dietary program among various online sites as well as offline media, including textual resources (like references to texts and cookbooks) and personal, lived experiences.

Although these groups provide widespread access to the key concepts behind their respective dietary programs, they often dilute those concepts with unhealthy extremes or even information that is plainly false. Much research (e.g., Ghaznavi & Taylor, 2015; Tiggemann, Churches, Mitchell, & Brown, 2018; Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2015; Deighton-Smith & Bell, 2018) has explored the harms and benefits of social media communities surrounding “thinspiration” and “fitspiration,” which Tiggemann et al. (2018) define as “contemporary online trends designed to inspire viewers towards the thin ideal or towards health and fitness respectively” (p. 133). These studies demonstrate the ways in which the “social” aspect of social media works to reinforce existing mentalities relating to the desire for a certain body type, as well as strategies for achieving that body type. They also demonstrate the unhealthy extremes that these communities can harbor. Conversely, Goodyear, Armour, and Wood (2018) and Napolitano et al. (2017) argued that, when used appropriately, social media can serve as a valuable resource for educating young people about health-related information, including nutrition. This is only a small sampling of interdisciplinary work that demonstrates the role of online communities in crafting and sharing discourse regarding weight loss and nutrition.

This study examines one such community: the Whole30 Community Facebook page. Through a memetic rhetorical analysis, this study demonstrates that the transmediational nature of this content and community re-constructs the way participants on this page understand the credibility of information relating to their nutritional needs. For technical communicators who routinely craft scientific information, like nutritional information, for public audiences, this re-construction is highly illustrative; it demonstrates the need for a thorough understanding of the affordances and rhetorical construction of the various media on and through which a community is built prior to crafting content for that community. Without such an understanding, researched and well-written content can be disregarded, or can become a source of misinformation itself, when it moves across media and into different contexts.

Background

Weight loss regimens and fad diets are among the most common and easily accessible examples of conflict among public audiences and scientific practitioners. Even a casual observation of public weight loss discourse shows contradictory ideas (Is animal fat helpful or harmful for weight loss? Do we need to eat carbs if we aren’t endurance athletes?) and leaves many dieters frustrated and skeptical of nutritional science. The Whole30 is one such nutritional program; it provides guidelines for a particular style of eating and challenges participants to commit to this eating program for a 30-day time period without lapses. This program originated in 2009 through a series of blog posts authored by its creators, Melissa and Dallas Hartwig. Since that time, the program has expanded to include several books, a thriving online community spanning the program website and several social media channels, and participants around the world. The focus of this program is on spending 30 days practicing what the Hartwigs call “Eating Good Food” or, to put it a different way, not eating all of the following:

- Added sugar, whether natural or artificial

- Alcohol

- Grains of any kind, including corn, rice, oats, and wheat as well as quinoa and amaranth

- All forms of beans, including soy products and their derivatives

- Dairy of all varieties

- Any food with MSG or sulfites

- Any food that is made from compliant ingredients but visually or psychologically mimics “bad foods” (Hartwig & Hartwig, 2014)

The theory behind these restrictions is that they prevent participants from consuming foods that might trigger personal sensitivities, like hidden allergic reactions, and they deny participants the possibility of eating for emotional reasons. The intensive restrictions also encourage conscious eating habits, such as reading nutrition labels on packaged foods, and are characteristic of a nutritional “reset” that the program creators claim re-orients the body biologically to have a healthier relationship with food (Hartwig & Hartwig, 2014).

The Whole30 books (which form the exigency for the Facebook community page) contain explicit conversations about building the credibility of the program. There is a significant amount of seemingly valid nutritional science that is built into the Whole30 program. Melissa Hartwig herself is a certified sports nutritionist, and the use of elimination diets to gauge the effects of certain food groups on an individual’s medical condition is not uncommon. In fact, much of the “scienc-y stuff” (to use the official Whole30 terminology) that the Whole30 literature references appears to come from peer-reviewed medical, nutritional, and psychological journals, and credible nutritional organizations. As such, it is here that we see the first shift is medium for content that was presumably written by scientists and technical communicators; it is moving out of the realm of academic discourse and into a genre most akin to a self-help book.

Within the context of the Whole30 books, the connection between academic/scientific research and the information provided is deliberately de-emphasized. In the texts, the Hartwigs discuss the credibility of the program (the fact that it “works” for dieters in various ways) as being separate from its connections with established scientific methods. Specifically, they say the credentials they as authors hold, and the peer-reviewed research built into the program, are (and should be) insufficient to convince people that the program works. This characterization of the relationship among peer-reviewed research, observation, and personal experience indicates a certain degree of mistrust in relying solely on established scientific methods; they are characterized as impersonal and often inaccessible, through the contrast between phrases like “academic evidence” and “boots-on-the-ground experience.” In this way, the rhetorical communication of the Whole30 program deliberately challenges conventional wisdom that claims that academically and professionally certified doctors and nutritionists are the best and most reliable sources of information about health and nutrition.

This article uses memetic rhetorical theory (MRT, coined in Davis, 2018) to analyze the consistency of content between the Whole30 books and the Whole30 Facebook community page. By determining what content changes and what content remains the same as the communicative scenario moves through and across different media, this analysis demonstrates it is possible to retain key content points when those content points are well-suited to the various media in which they will appear.

Methods

In this process, I began by using inductive coding to identify key elements, or memes, that characterize the collection of Whole30 books authored by Melissa and Dallas Hartwig, taking into account memes relating to both interface and content. I then followed the same process of inductive coding to identify the key memes that characterize the Whole30 Community Facebook page. Based on a thorough comparison of the content memes that appear consistently in both media, as opposed to those that are relegated to only one, I argue that the interface memes that characterize these media exert significant influence over the ability of content and ideas to transfer across media in a transmediated community.

Memetic Rhetorical Theory as Methodology

Based in the study of memetics, MRT offers a framework for understanding how memes; which can be information, media, technologies, cultural tropes, and rhetorical practices, among other things; adapt to gain persuasive power in communicative situations. In the development of MRT, I focus on the ways in which combinations of technological, material, social, and rhetorical factors collaboratively determine the construction of ethos in a given environment. This model relies on an understanding of content as subject to change over time and through transition but also characterizes that change as environmentally responsive, rather than solely the result of conscious changes made by composers.1

A meme in memetics and MRT is both a theoretical concept and an agent that functions as a unit of communication. As such, in the formation of MRT, I rely heavily on Dawkins’s (1989) original definition of a meme (also used by Blackmore, 1999, and others) as any feature of communicative interaction that replicates (that is, is used or appears more than once in a communicative scenario). However, I distinguish my definition from that of both Dawkins and Blackmore with the addition of non-human actors as agents of communication, meaning that memes do not need to be transmitted by humans alone but can also be transmitted by technologies or physical conditions. As such, I define any unit of communicative action as a meme, provided that it meets the following criteria:

- It must be repeated (replicated) at least once in addition to its original appearance in a given space;

- It must fulfill a rhetorical purpose by facilitating communication; and

- It must derive meaning for that purpose from contextual relationships with other memes in the same communicative situation.

According to this definition, examples of memes include those previously referenced but also include interface features, environmental factors, sounds, images, features of images, and any other discrete element related to communication that may or may not rely solely on human beings for transmission.

In strict adherence to these criteria, there are thousands of memes present in any communicative situation. In order for MRT to be a productive analytical tool, it must not only identify memes but also distinguish between memes that are merely present and memes that shape the interaction or system of interactions in which they appear to a greater or lesser degree. This distinction is possible by identifying disparities in the frequency with which these memes appear; the more often a meme appears, the more integral to the communicative situation it is. For example, consider the following situation: Heather is an engineer at an adhesives manufacturing company. When describing a new product to her team, she says, “It can be removed from any surface and then re-stuck easily, like an industrial grade Post-It note.” The comparison to a Post-It is picked up by the team’s technical writer and appears in the product overview. In this way, the conceptual link between this new product and the popular office supply replicates, it fulfills a rhetorical purpose by making the qualities of the new product easy to understand, and it derives meaning that helps it achieve that purpose from the contextual truth that all the readers of the product overview are aware of what Post-Its are and how they are used. This conceptual link between the new adhesive and Post-Its is a meme.

However, from this point, one of two things can happen: This meme can spread, appearing in other product-related media and discussions of the product among team members, or it can die off, appearing in just those two original instances, or only rarely thereafter. Which of these possibilities occurs depends on the other memes that characterize the communicative situation surrounding this particular product. It is in this sense that the adaptive nature of MRT becomes relevant. Because memes rely on each other to build meaning, memes appear more frequently when they correspond well to other memes that exist in the communicative situation.

If corporate culture at the adhesives manufacturing company mandates strictly technical jargon, the Post-It analogy is likely to seem unprofessional and will appear rarely, if at all. In this case, it would exert little influence over the communicative situation, because it would have so little exposure. If, however, comparisons to common products are used often in our adhesives manufacturing company, or if a conversational tone is typical in product communications, the Post-It meme is likely to spread. The more often a meme appears, then, the more influence it has over which other memes appear in that communicative situation, so the presence of the Post-It meme could even create increased likelihood of success for similar memes in the future.

This mutually constructive element of memes necessitates an understanding of how memes fit and work together; a productive study of memes should never consider them in isolation. Blackmore (1999) draws on Speel (1995) in her use of the term “memeplexes” as a shorthand for the more cumbersome “co-adapted meme complexes” (p. 19). These are groups of memes that evolve together over time, building on one another’s successes and creating frames of reference that determine the survival rate of new memes that emerge near them. As such, memeplexes are characterized by the internal compatibility of the memes they contain; they complement one another but are not identical. In the above example, the prevalence of comparisons to common products would qualify as a memeplex, while individual memes within that memeplex might involve the Post-It meme, a company-wide habit of discussing products face-to-face where such colloquial analogies are likely to come out, a recent likening of a label cutter to a light saber, and a similar analogy linking two-dimensional bar codes to floppy discs, among others.

It is this compatibility function that allows memeplexes to act as both gatekeeping mechanisms and mutually constructive forces for emerging memes. The co-adaptive nature of memes and memeplexes in a communicative situation creates environments that are conducive to the spread of some content and communicative actions but detrimental to others. It is, therefore, through successful adaptation to a communicative situation—the combination of technological, material, social, and rhetorical factors in an environment—that new content is able to spread successfully, thereby gaining persuasive power.

In these communicative situations, memeplexes are made up of memes that serve a variety of communicative functions. Some of these functions have to do with the formation and definition of content, while others have to do with the media and interfaces through which the content is communicated; I will call these content memes and interface memes, respectively. Because content memes and interface memes co-adapt to create the memeplexes that define communicative situations, technical communicators who work in transmediated communicative situations, like that of the Whole30 community that will be discussed in the following sections, must make use of interface memes that are afforded by the various media available to them in order to avoid unwanted shifts in content memes across media. Such unwanted shifts in content memes can drastically alter both brand voice and message, and can even contribute to the spread of misinformation.

In the case of the Whole30, the interface memes that characterize the Whole30 Facebook community page do not detract from all the content memes present in the Hartwigs’ original books but rather intensify some of them. In the following sections, I postulate that this is because the interface memes of the books and the interface memes of the Facebook community page, while different, serve similar rhetorical functions: They all de-emphasize the necessity for expert research. Therefore, the content memes that align with this disregard for expert research maintain their integrity when they move across media.

Data Collection

I began my memetic rhetorical analysis by using inductive coding to identify the controlling memes at play in the books that form the foundation of the Whole30 program. These books serve as comprehensive reference guides for Whole30 dieters. Their titles are as follows:

- Food Freedom Forever: Letting Go of Bad Habits, Guilt, and Anxiety Around Food

- Whole30 Cookbook

- The Whole30: The 30-Day Guide to Total Health and Food Freedom

- It Starts with Food

I considered this set of books as a single, complex memeplex (each book alone is, of course, also a memeplex). Within this memeplex, I followed a process of inductive coding to identify memes that appear in each book. Next, I compared the lists of memes that appeared in each individual book to identify memes that were consistent between books. Next, it was necessary to determine how often these commonly appearing memes materialize in the collection, so as to gauge their relative influence within the memeplex. The Whole30 Cookbook and The Whole30: The 30-Day Guide to Total Health and Food Freedom are segmented using units within major headings, while It Starts with Food and Food Freedom Forever use chapters. As such, I determined the frequency with which each meme appeared by calculating the percentage of segmented units (the term I will use as a consistent referent to both chapters and units within major headings) in which that meme appeared. I identified specific memes as influential based on the relative frequency with which they appeared throughout the books when compared with the average frequency of other memes that fulfill similar roles. This method allowed me to determine the controlling memes in this memeplex.

To understand if and how the memes from the books transfer across media in this transmediated community, I followed the same process of inductive coding to analyze the officially sanctioned content on the Whole30 Facebook page as well as community posts between January 1, 2018, and March 1, 2018. These dates are significant, because activity on the page increased dramatically during the early months of the year, affording an analysis with adequate data to characterize community trends. I chose to extend the analysis over two months because of the 30-day nature of the program. I noticed that many community members posting on the Facebook page were beginning their Whole30 Challenge early in January (as is not unusual with diet changes) and felt that it was important to allow enough time in my study for the original posters to finish their program and for other, new participants to begin. This helped to ensure that I was not unnecessarily limiting the scope of the communicative situation by focusing specifically on one cohort of Whole30 participants. It also provided me with a picture of the communicative situation that spans all the stages of the program, rather than appearing artificially focused on the early days.

Results

Influential Memes in Whole30 Books

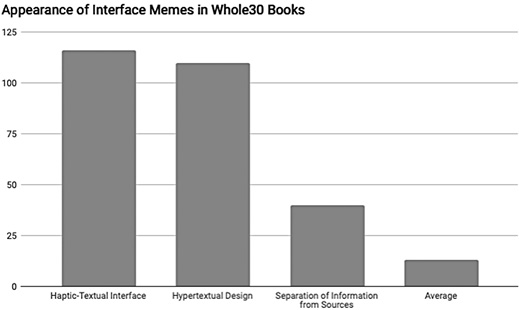

The following paragraphs identify the most prevalent and, therefore, the most influential, memes in the Whole30 books. Comparison of the frequency of appearance of interface memes in the Whole30 books indicated three interface memes that have a markedly higher relative frequency of appearance (see Figure 1) when compared to the average frequency of appearance of other interface memes in the books. These three memes can therefore be understood as key to the delivery of the information in all four books.

Figure 1. This chart shows the comparative frequency with which memes fulfilling a mediational function appear in the Whole30 books. The average appearance of memes fulfilling this function is roughly 13 appearances in 116 total segmented units (just over 10%). Haptic-Textual Interface memes appear in 100% of segmented units, Hypertextual design memes in 94.8%, and Separation of Information from Source memes in 34%.

Identifiable but minimally influential interface memes (i.e., photographs, charts and diagrams) appeared in just over 10% of segments, on average. The most influential interface memes—haptic-textual interface, hypertextual design, and the physical separation of information from sources—appear much more frequently. Figure 1 demonstrates this contrast. These influential memes are defined as follows:

- Haptic-Textual Interface: The qualities of touchable, text-based interaction that requires intersecting combinations of literacies, economic access, and embodied accessibility, and mobility of the book (i.e., page-turning) to access and understand the information it contains. It is worth noting that this meme is characteristic of all printed books.

- Hypertextual Design: The writing and formatting not only allow for but also actively encourage non-linear reading. This meme appears in several instantiations, including textual indicators to “skip” or focus on upcoming sections to achieve specific goals or cater to specific interests, calls forward or backward to other chapters (including references to other recipes as ingredients in recipe sections), call-out or definition boxes that allow readers to skim or refer back to content to grasp important ideas, and even chapter titles that facilitate selective reading.

- Separation of Information from Sources: This involves physical distance—in this case, often several pages or the entire contents of the book, between the location on a page where information from a reference source is given and the citation where that source is named using any readily identifiable information. This is in contrast to more common ways of referencing external sources in print media, wherein a parenthetical or sentence-form citation appears in close proximity to the material that has been drawn from the source in question.

Together, these memes govern the ways that information is presented in the Whole30 book series. Notice that while the haptic-textual interface meme is characteristic of all printed books, hypertextual design and the separation of information from sources are not. However, if any of these three memes were missing, the other two memes would function differently in this communicative scenario. In a print book, wherein it is easy to skip a table of contents and no sources are cited directly in the text (separation-of-information-from-sources meme), the references, where they exist at the end of the chapter or book, are rhetorically de-emphasized. The reader may not even notice they are there, and, if they do, with no authors named in the text, it is nearly impossible to align content with the sources from which it originates. Likewise, the hypertextual design of the books encourages readers to follow their own direction, rhetorically assigning them agency and authority in their reading experience, which is easily achieved in a haptic-textual format.

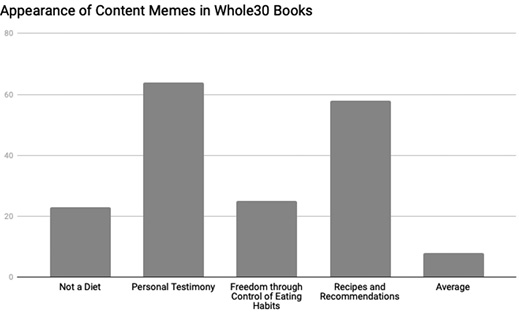

In addition to these three interface memes, I also identified four content memes that act as foundational ideas within the body of the text. These four memes had a markedly higher relative frequency of appearance (see Figure 2) when compared with the average frequency of appearance of other content memes, and can therefore be understood as characteristic of formative ideas within the body of texts. These are concepts on which the reasoning and persuasive power of the Whole30 program relies and that readers must buy into if they are to be effectively persuaded by the rest of the content. These memes are defined as follows:

Figure 2. This chart shows the comparative frequency with which foundational content memes appear in the Whole30 books. The average appearance of memes fulfilling this function is roughly 8 appearances in 116 total segmented units (just under 7%). The “Not a Diet” meme appears in 20% of segmented units, Personal Testimony in 55%, Freedom Through Control of Eating Habits in 26%, and Recipes and Recommendations in 50%.

- Not a Diet: This meme refers to the framing of weight loss as a supplemental and less-important benefit when compared with the other outcomes claimed by the program, like improved mood, better overall health including the elimination of existing diseases or reduction of symptoms. Similarly, the author(s) repeatedly note that the Whole30 is intended to permanently change the way that participants interact with food. This positioning contrasts with traditional diets, which are characterized in this meme as quick-fix, short term solutions tied primarily to a desire to lose weight.

- Personal Testimony: Personal testimonies refer to the inclusion of direct quotes or anecdotes from individuals who self-identify as having completed the Whole30 program and experienced specific benefits as a result.

- Freedom through Control of Eating Habits: This meme refers to descriptions of unhealthy relationships with food that equate these relationships with a prison sentence or a war zone. It emphasizes the anxiety that people often feel in eating situations when they feel powerless to overcome their cravings. Freedom, then, is characterized as the absence of this anxiety and the understanding that it is possible to escape from unhealthy cycles.

- Recipes and Recommendations: This meme focuses on strategies for success within the program and, as such, describes suggested recipes, tools for meal planning, and recommendations for specific best practices while completing the program.

Influential Memes on Whole30 Community Facebook Page

The following paragraphs identify the most prevalent and, therefore, the most influential, memes that make up the Whole30 Community Facebook Page. A comparative analysis of the relative frequency with which interface memes appear on this page when compared to the average number of appearances of interface memes on this page indicated that (1) an emphasis on users in page and content design, and (2) the spatial grouping of posts and comments are standard interface features of the Facebook site. Unsurprisingly, for a social media site that does not allow substantive customization of page interfaces, these interface memes are not unique to the Whole30 page. These interface memes are standard to the page and are therefore present whenever content is uploaded, so both are present in 100% of posts analyzed. This universal presence also means that other, optional interface memes, such as the inclusion of hashtags to organize content, appeared too rarely compared to the average appearance of interface memes on this page to be significant influencers within this memeplex.

- User Emphasis: In the Facebook community page—and on Facebook, generally speaking—there is a close spatial link between the content a user posts and that user’s identifying information, including their name (as designated on their account) and profile picture. On the screen, the user’s name appears in a larger font, bold typeface, and navy-blue coloring, which emphasizes the user who contributed the content before the type of the content itself.

- Spatial Grouping of Posts: Comments, likes, etc., appear in close proximity to original content and in chronological order. These are organized on the page chronologically by contribution, meaning that the position of the post on the page depends on when it was uploaded and not on who uploaded it. As such, the narrative that a reader experiences is the narrative of the page as a whole, as a set of isolated content interactions, not the comprehensive narrative of a single user’s experience, or a set of recognizable individual users’ experiences.

The combination of these two memes creates an interface memeplex that privileges perception of the user as an abstract concept rather than an individual. Due to the spatial separation of individual posts by the same user from one another, and the fact that the community page, rather than the profiles of individual users, is the primary locus for interaction, users on this particular page are never able to develop complex personae.

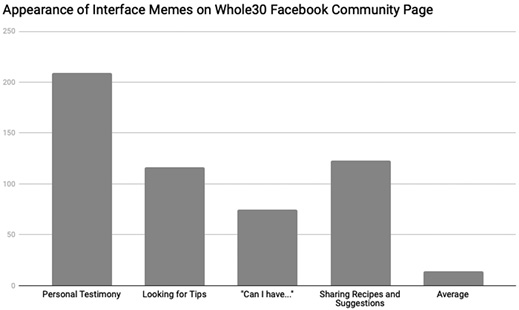

Figure 3. This chart shows the comparative frequency with which foundational content memes appear in posts on the Whole30 Community Facebook page. The average appearance of memes fulfilling this function is roughly 14 appearances in 426 total posts (about 3%). The Personal Testimony meme appears in 49% of posts, Looking for Tips in 27% of posts, “Can I have…” in 18% of posts, and Sharing Recipes and Suggestions in 29%.

Likewise, I identified four content memes that appear most frequently on the page. These memes were, again, indicated through analysis of the frequency with which they appear on the page as compared to the average frequency of appearances of other content memes. Figure 3 illustrates this comparison. This frequency was analyzed through inductive coding of all 426 posts that appeared on the page in the specified timeframe, with some posts containing multiple memes. These content memes are defined as follows:

- Personal Testimony: Community members use the forum space to report on their personal progress, intentions, or results. This often takes the form of a simple summary of where the user is in the program (abbreviations such as R2D16, for “Round 2, Day 16” are common) and/or a brief discussion of how the program is going for them. Users will occasionally point out problems they are encountering or benefits they are observing. This meme also manifests as individuals indicating the start (or plans to start) or end of their Whole30 program.

- Looking for Tips: Community members use the forum space to ask others for advice on solving specific problems related to the Whole30. These often have to do with incorporating existing habits into the Whole30 lifestyle (i.e., a user might indicate that they are used to taking protein supplements after a workout and ask if anyone knows how to get the same level of protein intake in a compliant way) but might also include requests for advice about cooking or shopping techniques, or general, “I’m new to this, does anyone have any tips?” style posts.

- “Can I have…”: Users often post inquiries about foods or specific ingredients, asking others if these are allowable on the program. In many cases, the user will include a picture of the food (especially the ingredients list) along with their post. This meme is distinct from “Looking for Tips,” because the users are seeking “yes” or “no” answers regarding a specific food or product rather than advice more broadly.

- Sharing Recipes and Suggestions: These are unsolicited posts (i.e., they are not in response to specific requests for suggestions) that users share on the community page containing references to brands or products that are Whole30 compliant, or recipes for compliant meals. This meme, like others I have discussed, appears in a few different manifestations. Some are full recipes containing lists of ingredients, preparation instructions, and cook times, others are simply pictures of food with a brief endorsement (“yum!”), and still others are reports that the user has discovered a food that they like that is compliant with the plan. Many are combinations of one or more of these manifestations

Together, these two interface memes and four content memes combine to form the memeplexes that define the communicative situation of Whole30 Facebook community page. Notice the difference in the interface memes and the only partial overlap in the content memes between the books and the Facebook page, which the following analysis will discuss.

Analysis

The interface memes and content memes defined in the above sections are fully dependent on one another within the confines of the memeplexes that characterize the books and the Whole30 Facebook community page, respectively. Together, the interface and content memes in each space form the memeplexes that define that space. The varying dynamics between the memeplex of the books and the memeplex that shapes the Facebook page determines what memes will succeed or fail when they move from the books to the Facebook page in this transmediated communicative situation. The interface memes in particular (and the memeplexes they create) are markedly different between the Facebook Community page and the Whole30 published books, which causes other memes to shift and adapt accordingly. Yet, while these interface memes present differently across media, both sets rhetorically emphasize the experiences of users over researchers as content experts, effectively centering credibility around personal experience.

Two memes from the books appear prominently in the Whole30 Facebook community: Personal testimonies and recommendations/recipes. Both of these, however, have evolved to better suit the communicative situation of the Facebook community page.

Instead of manifesting solely as static reports as they appear in the books, personal testimonies on the Facebook page include elements of personal tracking as well. When reporting their results, users mention where they are in the program (including when or if they have finished) and specific details of their progress in time-oriented phrasing (i.e., “R1D15, my skin has cleared up and I have TONS of energy”). This evolution shows co-adaptation of the testimony meme with the user-focus meme within the Facebook interface memeplex, as it is specific to that user and tied to the user’s account, rather than being selected by authors or cite administrators and used as a frame of reference. Because of the anonymous yet personal quality of the Facebook interface memeplex, personal testimony memes are rhetorically constructed as being generalizable to the average page user. The interface memeplex helps to define credibility in this community based on personal results, so users know a testimony is credible and that they can achieve similar results specifically because another user shared this as their own experience. In this adaptation, the content meme of personal testimony stayed true to its original purpose as it appeared in the Whole30 books. However, the original scientific research that prompted the practices on which the testimonies are based have been lost.

The recipes and recommendations meme likewise evolved to suit the Facebook communicative situation. In the books, the recipes are detailed (typically, one page) and often organized by category, cookbook-style, so that finding desired recipes is facilitated by the hypertextual design. The recommendations are also detailed and often supported by what the authors call “scienc-y stuff” (read: research). On the Facebook page, however, recipes tend to either be short and non-descriptive, including only ingredient proportions and summary instructions, or simple links outward to other sites, while recommendations come in the form of simple endorsements or images of food products or brands. While links outward occur, these are framed in the context of recommendations or suggestions, again meaning that the inclusion of the content is contingent on the original poster’s personal experience with it rather than any intrinsic quality of the linked content itself. Hence, the credibility of the post relies on that recommendation meme and the content only spreads as a result of its inclusion.

The multi-user site interface also allowed the recipes and recommendations meme from the books to evolve into requests for information that users can expect to be answered. This function created the looking-for tips and “Can I have…?” memes that are present on the Facebook site. The communicative situation of the Facebook page, which utilizes interpersonal communication and includes the sharing of recipes and recommendations, allows memes that seek out this kind of information to co-exist symbiotically.

These posts rely on the credibility of the named yet anonymous user, much like the testimony memes; however, recipes and recommendations are focused on specific products and strategies rather than an anticipated outcome. The shared source of credibility means that testimony, and recipes and recommendations, are rhetorically linked within the site interface, suggesting that even though all of these are posted by different users, utilizing the recipes and recommendations from one group of users will allow page readers to achieve the same results as the users who reported their tracking and testimony.

This analysis demonstrates that the memes from the Whole30 books that carried most successfully onto the Facebook community page are those that were already well-suited to the named yet anonymous user-focused interface memeplex that defines the Facebook community page. These memes adapted slightly, but they maintained their original message as well as the rhetorical effect utilized by the Hartwigs in their books.

Conclusion

The combination of these interface and content memeplexes means that the Facebook community page is a communicative situation that not only emphasizes but is built on personal testimony and anecdotal results. These are used as community resources as well as support mechanisms, meaning that they are among the most common and integral memeplexes in this communicative situation. Credibility in this communicative situation is derived from the relationship between information and individuals, not from scientific methodology or personal credentials. As such, attempts to intervene in potentially unhealthy habits, or to spread new and beneficial research-based content in this forum, are unlikely to be successful, unless they make intentional use of this focus on individual experience.

Situations like this are common on social media, where the social focus leads users to rely heavily on content from one another, and direct engagements by experts are both rare and undervalued. It is important for technical communicators who produce content for public consumption to be aware of this phenomenon. When engaging with transmediated communities, it is the content that is best suited to the communicative situation within each medium that retains its credibility in that space. As such, content that is integral to users’ well-being or productive interaction with a concept or product must be composed from the start for transmediation.

Endnotes

- For a full description of memetic rhetorical theory, see Davis (2018). This analytic model builds on Ridolfo and DeVoss’s (2009) definition of rhetorical velocity, which is a useful term for understanding information transfer among users, among other key theoretical concepts.

References

Blackmore, S. J. (1999). The meme machine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bode, L., & Vraga, E. K. (2015). In related news, that was wrong: The correction of misinformation through related stories functionality in social media. Journal of Communication, 65(4), 619–638. doi:10.1111/jcom.12166

Chong, F. (2018). YouTube beauty tutorials as technical communication. Technical Communication, 65(3), 293–308.

Davis, C. J. (July 2018). Memetic rhetorical theory in technical communication: Re-constructing ethos in the post-fact era. (Doctoral dissertation). East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina. Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/10342/6935

Dawkins, R. (1989). The selfish gene. New York, NY: Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deighton-Smith, N., & Bell, B. T. (2018). Objectifying fitness: A content and thematic analysis of #fitspiration images on social media. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 7(4), 467–483. doi:10.1037/ppm0000143

Ding, H. (2009). Rhetorics of alternative media in an emerging epidemic: SARS, censorship, and extra-institutional risk communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 18(4), 327–350. doi: 10.1080/10572250903149548

Dixon, G. N., McKeever, B. W., Holton, A. E., Clarke, C., & Eosco, G. (2015). The power of a picture: Overcoming scientific misinformation by communicating weight-of-evidence information with visual exemplars. Journal of Communication, 65(4), 639–659. doi:10.1111/jcom.12159

Ghaznavi, J., & Taylor, L. D. (2015). Bones, body parts, and sex appeal: An analysis of# thinspiration images on popular social media. Body image, 14, 54–61.

Goodyear, V. A., Armour, K. M., & Wood, H. (2018). Young people and their engagement with health-related social media: New perspectives. Sport, Education and Society, 1–16 doi: 10.1080/13573322.2017.1423464

Hartwig, M. (2016). Food freedom forever: Letting go of bad habits, guilt, and anxiety around food. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Hartwig, M. (2016). The Whole30 cookbook: 150 delicious and totally compliant recipes to help you succeed with the Whole30 and beyond. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Hartwig, D., & Hartwig, M. (2014). It starts with food: Discover the Whole30 and change your life in unexpected ways. Las Vegas, Nevada: Victory Belt.

Hartwig, M., & Hartwig, D. (2015). The Whole30: The 30-day Guide to Total Health and Food Freedom. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Kimball, M. A. (2017). The golden age of technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 47(3), 330–358. doi:10.1177/0047281616641927

Kite, J., Foley, B. C., Grunseit, A. C., & Freeman, B. (2016). Please like me: Facebook and public health communication. PLOS ONE, 11(9). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162765

Napolitano, M. A., Whiteley, J. A., Mavredes, M. N., Faro, J., DiPietro, L., Hayman, L. L., & Simmens, S. (2017). Using social media to deliver weight loss programming to young adults: Design and rationale for the healthy body healthy U (HBHU) trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 60, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2017.06.007

Ridolfo, J., & DeVoss, D. N. (2009). Composing for recomposition: Rhetorical velocity and delivery. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 13(2), n2.

Speel, H.C. (1995). Memetics: On a conceptual framework for cultural evolution. Paper presented at the symposium ‘Einstein meets Magritte,’ Free University of Brussels.

Tiggemann, M., Churches, O., Mitchell, L., & Brown, Z. (2018). Tweeting weight loss: A comparison of #thinspiration and #fitspiration communities on twitter. Body Image, 25, 133–138. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.03.002

Tiggemann, M., & Zaccardo, M. (2015). “Exercise to be fit, not skinny”: The effect of fitspiration imagery on women’s body image. Body Image, 15, 61. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.06.003

van Ittersum, D. (2014). Craft and narrative in DIY instructions. Technical Communication Quarterly, 23, 227–246, doi:10.1080/10572252.2013.798466

Waszak, P. M., Kasprzycka-Waszak, W., & Kubanek, A. (2018). The spread of medical fake news in social media – the pilot quantitative study. Health Policy and Technology, 7(2), 115–118. doi:10.1016/j.hlpt.2018.03.002

About the Author

Carleigh Davis is an Assistant Professor of Technical Communication at Missouri University of Science and Technology in Rolla, Missouri. Her research focuses on the rhetorical construction of online communities and the spread of mis/disinformation in digital spaces. She is available at daviscarl@umsystem.edu.

Manuscript received 25 May 2019, revised 2 June 2019; accepted 5 June 2019.