Abstract

Purpose: To empirically examine and document knowledge sharing patterns that practitioners employ in blog conversations about research and work experiences.

Method: We conducted an empirical analysis of 235 blog posts from June 2014 to March 2016. We analyzed and coded each post for 14 unique variables including article type, topic, and citation style. We then analyzed the data using both descriptive and inferential statistics in order to reveal patterns in the data.

Results: An overwhelming majority of the blog posts were written by practitioners for practitioners. Of the 235 blog posts, the most common topics were technology, professionalization, and communication strategies. Of the technology posts written, DITA was by far the most common technology topic. The most common article types were argumentative, process, and how-to articles. While practitioners rarely blog about research, when they do, they spend most of their time writing about results and discussion as opposed to introductions or methodology. Finally, our analysis revealed that bloggers made intentional visual design choices when sharing knowledge via blogs.

Conclusion: Practitioners use distinct knowledge dissemination patterns in blog conversations that shape how research is presented to the technical communication community. Understanding these patterns is an important first step toward developing a shared language that will help bridge the gap in understanding between the academic and practitioner communities. Ultimately, blogs are a useful forum for studying practitioner conversations and developing broader understanding about what they value in their work and research.

Keywords: research, blogs, academy-industry relationships, shared language, quantitative analysis

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Extends previous studies of practitioners communicating on blogs.

- Provides practitioners descriptive accounts about how they share knowledge on blogs.

- Offers up-to-date understanding of topics that practitioners discuss on blogs.

- Provides valuable data for helping practitioners and academics develop a broader shared understanding about their work as a basis for facilitating communication between their communities.

Introduction

In technical communication, there is a documented disconnect between practitioners and academics (Boettger, Friess, & Carliner, 2015; Bridgeford & St.Amant, 2015; Rainey, 2005; Thrush & Hooper, 2006). This disconnect has led to poor communication between the communities including the delivery of research findings that this special issue is designed to address (Albers, 2015). Boettger, Friess, and Carliner (2014) describe the disconnect between academics and practitioners when they argue that the differences they found in practitioner and academic publications point to “differences in conversations of professionals and academics” (Boettger, Friess, & Carliner, 2014, p. 4). Their use of the word “conversation” is apt in that it implies a back and forth dialogue. Even more telling, however, is their argument that practitioners and academics seem to be having two distinct conversations, which points back to the divide that exists and the purpose for this special issue. In an ideal world, then, academics and practitioners would be having the same conversation—with both parties contributing and pushing forward the field together.

We argue that one way to begin the hard work of bridging the gap between these conversations is to draw from the concept of shared language described in interdisciplinary team research scholarship. Previous literature defines shared language as common vocabulary, jargon, codes, and linguistic styles (Austin, Park, & Goble, 2008; Chiu, Hsu, & Wang, 2006; Hannah & Saidy, 2014; Mamykina, Candy, & Edmonds, 2002; Milligan et al., 1999). However, the concept goes beyond language itself and addresses factors like the “subtleties and underlying assumptions that are the staples of day-to-day interaction” (Lesser & Storck, 2001, p. 836). This scholarship asserts that interdisciplinary teams made up of diverse individuals work more effectively when they develop a shared language. The first step in that process, however, is for individuals to develop a deep understanding of their counterparts by learning the “language” and conversational style of their counterparts.

Therefore, we believe that a necessary step for bridging the divide between academics and practitioners is examining practitioners’ current conversation. In order to study the conversation occurring among practitioners, we decided to examine blog posts of practicing technical communicators. We examine blogs because of their ubiquity and popularity as a knowledge-sharing forum (Cleary, 2012; Yang, 2009). In fact, research has argued that one of the primary motivations of blog authors is knowledge sharing (Chai, Das, & Rao, 2011) and community identification (Hsu & Lin, 2008). In addition, since blogs democratize the publication process (i.e., anyone can publish a blog with little barrier to entry), blogs provide an “unfiltered” look at the issues practitioners talk about in their research conversation as well how they talk about those issues. Within the technical communication community, blogs have been identified as a forum for holding conversations about issues surrounding professionalization in the field as well as to think strategically about the future by sharing information, networking, discussing events, explaining procedures, and engaging in conversations with their readers (Cleary, 2012). Beyond the field of technical communication, other professional communities of practice such as medicine (Hillan, 2003; Lagu, et al., 2008; Maag, 2005; Watson, 2012), sociolinguistics (Hinrichs & White-Sustaíta, 2011; Mynard, 2008), and education (Brescia & Miller, 2006; Makri & Kynigos, 2007; Yang & Chang, 2012) have examined conversations on blogs to understand how communities of practice develop the kinds of shared understanding that is necessary for communicating well with members within a diverse community of practice.

Based on this broad professional interest in and use of blogs, we studied how practitioners present and share knowledge on blogs because it provides an opportunity for academics to study practitioner conversation as a necessary first step toward developing a shared language that will create conditions for fostering communication with practitioner communities.

Toward that end, we begin the article with an overview of the relevant technical communication literature regarding the ways academics have attempted to bridge the gap of understanding with practitioners by reviewing previous research that has sought to learn about work practices, job skills, and literacies. Next, we offer a detailed outline of research questions that drive our study and then describe and justify our method for a study of 235 practitioner blogs and present the results of our research questions. We then provide a discussion of key findings and note their implications for bridging conversations about research between the academic and practitioner communities. Finally, we note the limitations of this study and suggest directions for future research.

How Academics Have Sought to Understand Practitioners

Academic research aimed at developing knowledge and understanding about practitioners’ work practices and professional interests has primarily focused on the following:

- Studying practitioners using primary research including surveys (Blythe, Lauer, & Curran, 2014; Carliner et al., 2009; Rainey, Turner, & Dayton, 2005) and interviews (Cooke & Mings, 2005; Whiteside, 2003).

- Examining technical communication job postings (Brumberger & Lauer, 2015; Lanier, 2009).

- Analyzing formal publications (Boettger, Friess, & Carliner, 2014; Boettger, Friess, & Carliner, 2015).

- Analyzing the content of technical communication blogs (Cleary, 2012).

Each of these lines of scholarship offers academics a different kind of insight about practitioners and the ways they work and communicate.

Understanding practitioners through surveys and interviews

Through surveys and interviews, academics have sought to learn about the realities of day-to-day industry practices. Practitioners have been studied as managers (Rainey, Turner, & Dayton, 2005; Whiteside, 2003), as graduates of technical communication programs (Blythe, Lauer, & Curran, 2014; Coon & Scanlon, 1997; Whiteside; 2003), and as industry specialists (Cooke & Mings, 2005). Though different in their approach, each of these studies shares in a general desire to bridge the gap between academic preparation and actual workplace practice by determining what skills, content knowledge, and writing and technology literacies are needed in the workplace (Henschel & Meloncon, 2014; Spilka, 2009). Overall, the knowledge shared by practitioners as primary research participants is valuable for its timeliness and responsiveness to contemporary work place demands; however, such information reflects only the perceptions of the small sample of individuals studied and therefore may not be adequately representative of the larger practitioner conversation in the field.

Understanding practitioners through technical communication job postings

Technical communication job postings provide insight about bridging the gap between academics and practitioners because they provide a clear, written record of skills and experiences desired for technical communication jobs. For instance, Lanier (2009) examined 327 job postings on Monster.com and found communication skills as the most sought-after skill by employers. Similarly, Brumberger and Lauer (2015) examined nearly 1,000 job postings from Monster.com and found that the postings exhibited a wide variety in job titles as well as diversity in the kinds of technology skills, competencies, and information products required for the different job types. Ultimately, these studies provide valuable insights about skills and competencies that employers value in applicants; however, because job postings are framed through a human resources perspective, there are inherent limitations to understanding practitioners and their work lives via job postings. In particular, the human resources frame elides facts or elements from practitioner conversations that illustrate the day-to-day realities of practitioners’ work.

Understanding practitioners through formal publications

Another avenue for bridging the gap between academics and practitioners has focused on examining the trade publication, Intercom. Boettger, Friess, and Carliner (2014, 2015) investigated alignment between academic, peer-reviewed journals and industry trade-publications and found that differences exist between the two types of publications. Specifically, the authors note that industry trade publications publish process and professional-oriented articles that focus on professionalization, technology, and editing and style, whereas academic publications tend to publish product and education-oriented articles that focus on assessment, research design, and comprehension. Together, these studies offer useful insights about the types and range of topics that practitioners write about. Our research differs and extends this line of research in that our work examines blog conversations to understand how practitioners share knowledge, which is different than knowledge sharing in Intercom in that the editorial process for blogs is significantly less rigorous than Intercom. Therefore, our study provides a broader look at practitioner conversations in the technical communication community.

Understanding practitioners via blogs

Unlike the prior three areas for developing practitioner understanding, blogs offer practitioners an unconstrained environment for conducting a conversation about their profession. As such, blogs represent a unique, up-close opportunity for academics to develop understanding of practitioners. Previously, Cleary (2012) studied ten practitioner blogs to examine how blogs reflect practitioner views of professionalization. Her findings revealed that practitioners were concerned with gaining respect for the field, understanding and standardizing routes to the field, and examining and understanding threats to the field. Cleary also identified a lack of engagement by academics on practitioner blogs, which is relevant to our study for her recognition of blogs as an opportunity for academics to engage in the practitioner conversation. As mentioned in the introduction of this article, other professional communities of practice like medicine (Hillan, 2003; Lagu, et al., 2008; Maag, 2005; Watson, 2012), sociolinguistics (Hinrichs & White-Sustaíta, 2011; Mynard, 2008), and education (Brescia & Miller, 2006; Makri & Kynigos, 2007; Yang & Chang, 2012) have used blogs to both develop and deepen shared understanding between its members. For example, in medical contexts, blogs provide a forum for physicians and nurses to share their narratives (Lagu et al., 2008), help create a sense of belonging and allow users to connect on their own terms (Hillan, 2003), and serve as a platform for nurses to learn from others (Watson, 2012). Of particular relevance to our study, medical blogs are being quoted or referenced in presentations, articles, and grant proposals (Watson, 2012). It seems, then, that academics in the field of medicine are using blogs to bridge a divide and enter into conversation with patients whom their work impacts. In a similar manner, this study seeks to examine how blogs might play a similar role in bridging the academic/practitioner divide.

Together, the above scholarship on blogs in professional communities of practice demonstrates the relevance of examining how blogs can help bring communities of practice together. Our study of technical communication practitioner blogs will add to this scholarship by looking at the dissemination patterns practitioners employ when sharing knowledge. We concede that some academic researchers may have little desire to engage in such a conversation and that there are even contexts in which such a conversation is not appropriate. However, we believe that understanding and engaging audience, in this case, a practitioner audience, is vital to the role of a technical communicator.

Research Questions

Based on the previous literature, we devised three sets of research questions. The first set of questions seeks to describe practitioner blog posts in an effort to better understand how practitioners disseminate knowledge. Second, we were interested in examining a sub-set of blog posts that centered on research-based blog posts in an effort to understand how and when practitioners conduct, reference, or apply research. Finally, the third set of research questions examines which types of blog posts generated the most engagement in an effort to determine what topics and types of articles practitioners are most drawn to. Below, we outline the specific research questions.

Describing practitioner blog posts

- Who writes technical communication blogs and who are the blogs written for?

- When practitioners disseminate knowledge via blogs, what topics do they publish about? What types of articles do they publish? Are they primarily publishing about the past, present, or future?

- How do practitioners design their blog posts? Are there shared visual design markers used by practitioners?

Analyzing research-based blog posts

- How often do practitioners write about or report on their own research?

- When bloggers cite other work, do they primarily cite academic research or other practitioner work?

- How do practitioners package and organize the delivery of research findings? Specifically, what percentages of their posts are dedicated to introduction, methods, results, and/or discussion?

Examining engagement in practitioner blog posts

- What topics generated the most engagement? (as measured by comments, retweets, and likes)

- What article types generated the most engagement?

Methodology

In the methods section, we describe our data collection, coding, and analysis in detail.

Samples and data collection

We analyzed a total of 235 blog posts written between June, 2014 and March, 2016. To obtain our sample, we started with Twitter to archive tweets marked with the hashtag #techcomm using Martin Hawksey’s Twitter Archiving Google Sheet (TAGS). This method of data collection was described in our previous article (Lam & Hannah, 2016a). Using TAGS, we collected 31,063 unique tweets. From those tweets, we filtered only tweets that included the word blog or postin them—1,517 tweets. We chose to filter tweets using the words blog and post because we assumed these words would likely appear in a tweet that was announcing a blog post on Twitter. Finally, from those 1,517 tweets, we removed duplicate tweets and ended up with a final number of 235 tweets that linked to unique blog posts.

We realize that this may not be exhaustive of every possible blog post written between the time period of June, 2014 and March, 2016; however, we made this methodological choice for two major reasons. First, following the hashtag #techcomm provided us with a contemporary and relevant collection of tweets about the field of technical communication because of the nature of the existing technical communication community on Twitter (see Lam, Hannah, & Friess, 2016). That is, an active community of technical communicators uses this hashtag for a variety of content related to the field. Second, the methodological alternative to using Twitter for locating blog posts involved a much less rigorous selection process (e.g., using a search engine and randomly selecting blog posts to analyze or analyzing posts from well-known bloggers). Our method allowed for an analysis of a wide variety of blog post authors and, thus, a wider vision of the field.

Variables

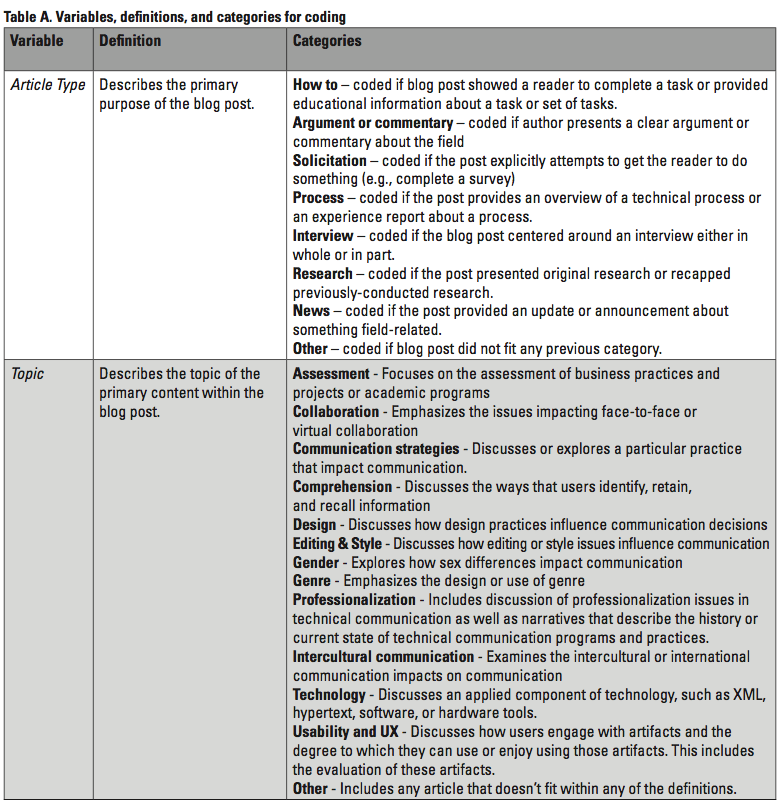

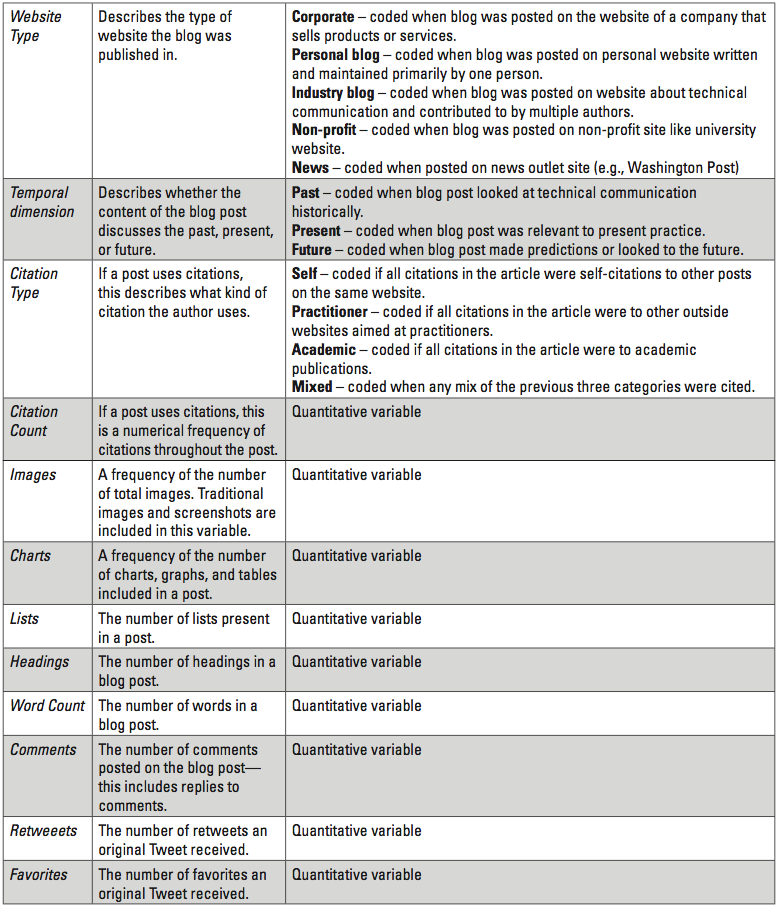

We collaboratively created a codebook that defined fourteen unique variables of interest based on our research questions. We came up with a set of mutually exclusive categories for the variables that can be found in Appendix, Table A. For one of the fourteen variables, topic, we adopted Boettger, Friess, and Carliner’s (2014) coding scheme that they used to code technical communication journal articles.

Coding procedure and interrater reliability

The first step in the coding procedure involved copying the URL that was captured in the original tweet and pasting it into a Web browser in order to view the blog post in its entirety. We then coded each blog post for the fourteen variables, recording the data in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. To record the number of retweets and favorites that the original tweet received, we copied and pasted the text of the original tweet into the search box of the Twitter website, which returned the original tweet. From the original tweet, we recorded the number of retweets and favorites.

While most of the variables did not require coder judgment (i.e., most variables involved simply recording quantitative variables), three variables required subjective coder judgment: topic, article type, and temporal dimension. To ensure interrater reliability, the authors independently coded the same 51 (22%) blog posts within the sample. Boettger & Palmer (2010) suggest collectively coding 10% of the sample to establish interrater reliability. Therefore, we were conservative in our choice to collectively code 22%. We achieved high interrater reliability for all three variables: topic (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.76), article type (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.78), and temporal dimension (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.81). While there is no universal threshold when interpreting Cohen’s Kappa, most research suggests that any value over 0.7 is acceptable, and some research even suggests that any value over 0.6 is acceptable (Landis & Koch, 1977). Once we established interrater reliability, each researcher coded half of the remaining 184 tweets.

Data analysis

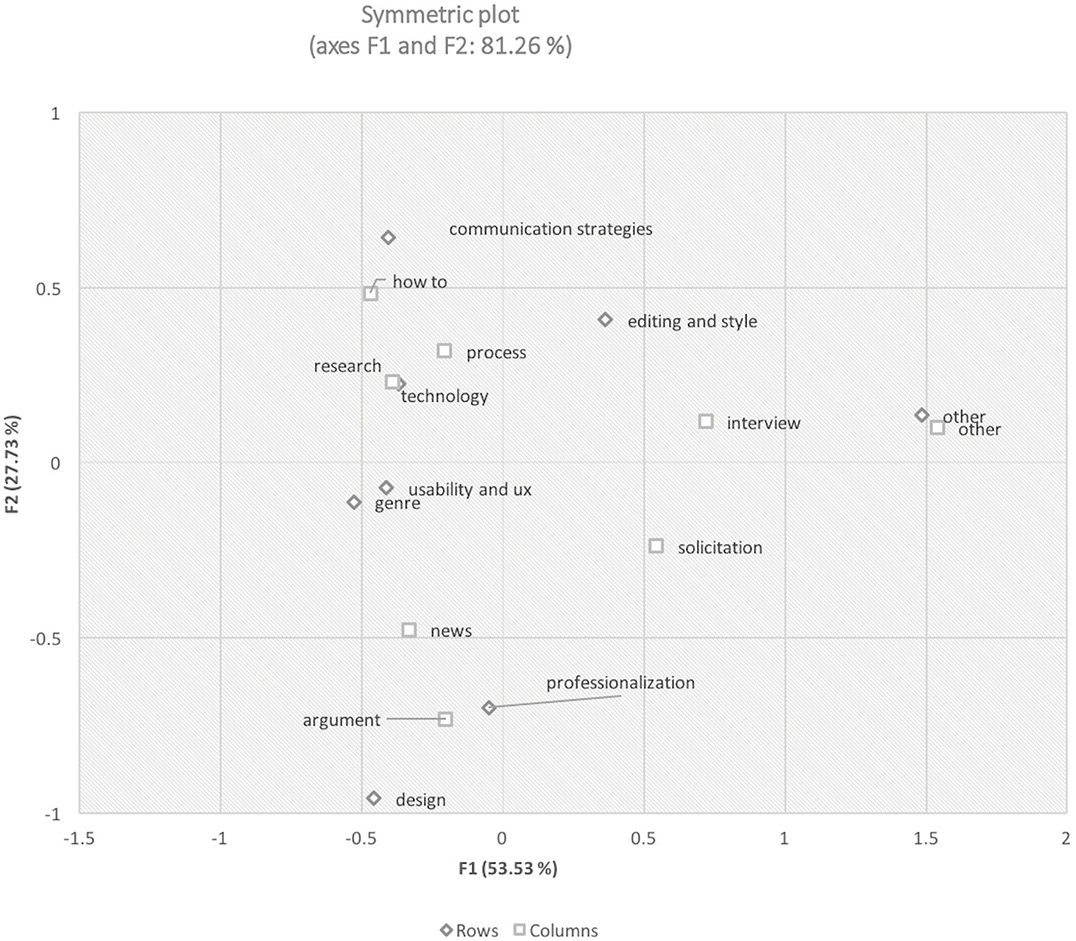

We used a variety of statistical tests to analyze our data including descriptive statistics (ratios, frequencies, and means). To analyze more complex relationships between categorical variables, we used correspondence analysis (CA)—a method that is relatively new to technical communication but utilized in several recent studies (Boettger & Lam, 2013; Lam & Hannah, 2016b). Simple CA is a geometric technique used to analyze two-way tables containing some measure of correspondence between the rows and columns. The central analytical tool in CA is its visualization of row points and column points onto a multi-dimensional graphical map called a biplot. Rows with comparable patterns, also known as profiles, appear in close proximity on the biplot. Similarly, columns with comparable profiles appear in close proximity on the biplot. When plotted together, the visualization allows a researcher to examine associations among row and column points (see Lam, 2016 for a full tutorial on how to implement CA into technical communication research).

Finally, to answer our final set of research questions, which involved both categorical and interval-level variables, we utilized the Kruskal-Wallis test as an omnibus test of topics and article types on engagement. The Kruskal-Wallis is a non-parametric alternative to the ANOVA. We chose to use the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test instead of the parametric ANOVA test because our data violated one major assumption of ANOVA: normality. Choosing the parametric test instead of the non-parametric counterpart increases the chances of a false positive, or type 1 error. When we found significance in the Kruskal-Wallis test, we conducted follow-up pairwise comparisons using the Dunn-Bonferroni method. This method uses Dunn’s test along with a Bonferroni adjustment to the significance value of pairwise comparisons in order to reduce type 1 error. Dunn’s test was used because it is an appropriate non-parametric post-hoc procedure that is used after a significant Kruskal-Wallis test (Dunn, 1964).

Before describing the results, we must also point out that when we describe relationships between variables, we are referring to a relationship among the derived coded variables from our coding scheme. That is, although our coding protocol produced adequate reliability, the codes themselves represent relationships among coded variables and may not represent relationships between actual empirical observations. This is an inherent limitation of the content strategy method that we want to explicitly acknowledge.

Results

In the results section, we will answer each set of research questions separately. We also provide some exploratory results that complement the research questions.

Describing practitioner blog posts

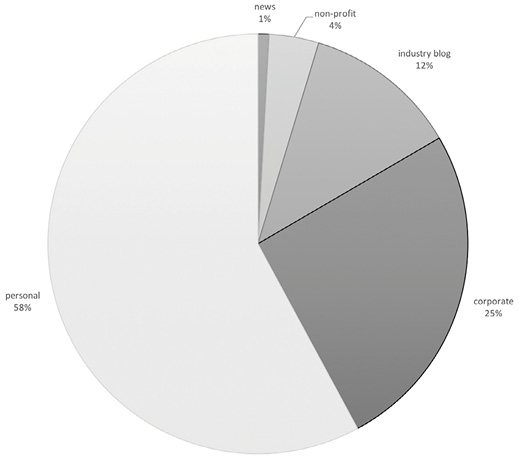

In our sample of blog posts written between June, 2014 and March, 2016, 98.29% of blog posts were written by practitioners and for practitioners (n = 231). The remaining blog posts were written by academics (n = 4). There were a total of 91 unique authors throughout the sample. Additionally, we examined the types of websites that the blog posts were published in. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the website types. As can be seen, the majority of the blog posts were written by individuals who write for their own personal blogs (n = 136). However, one-fourth of the blog posts were posted on a corporation-affiliated website (n = 60).

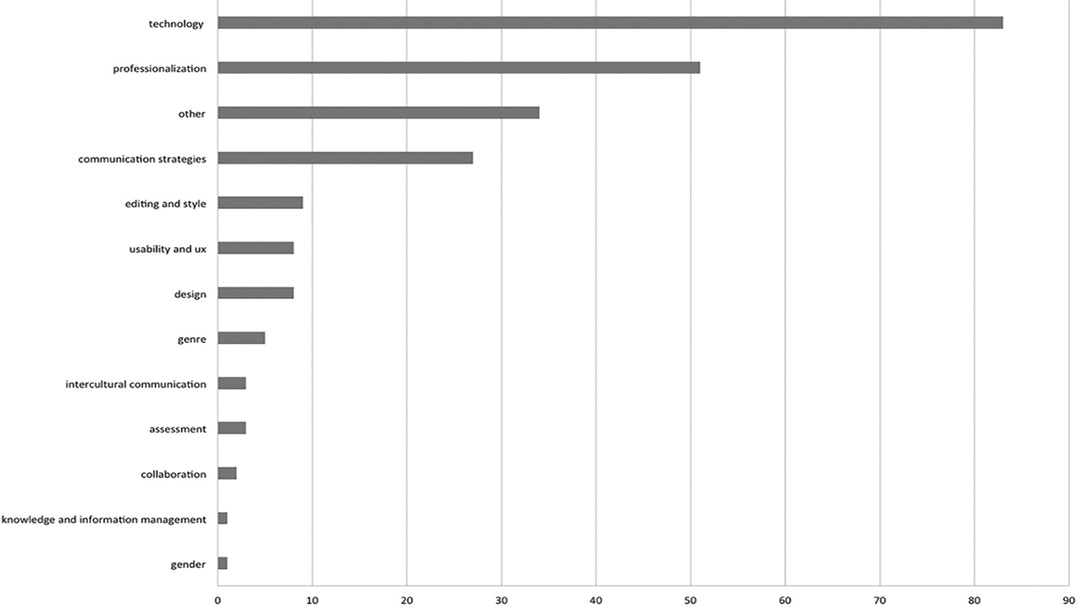

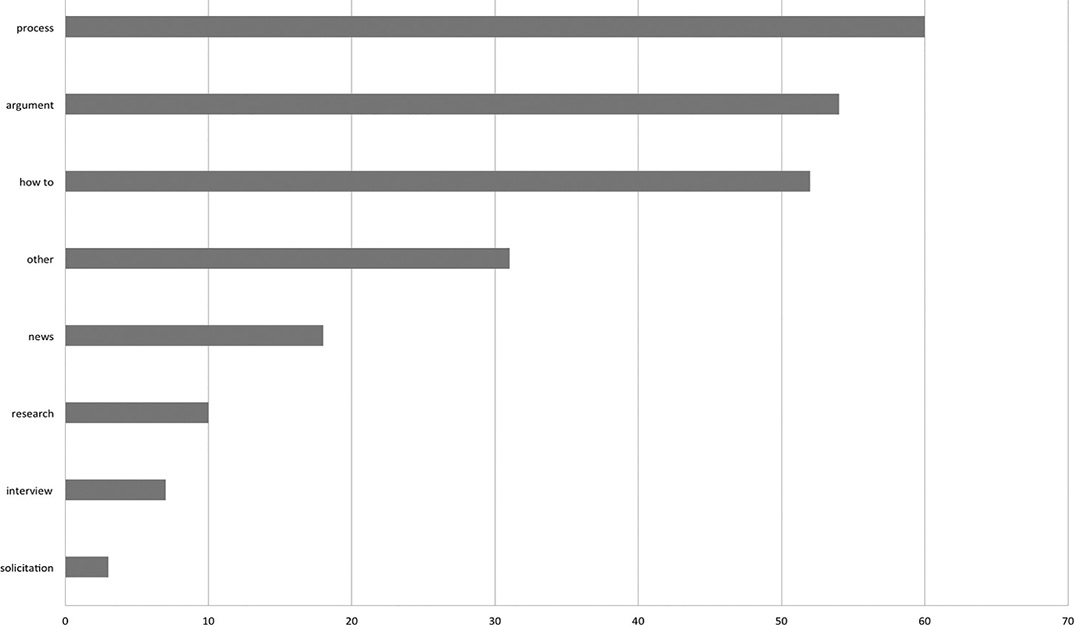

In addition to the authors, audiences, and venues for this sample of blog posts, we also coded the blog posts for topic, article type, and temporal dimension. Figure 2 shows the frequency for each topic in the sample. As can be seen, blog posts related to technology (n = 83) dominated the sample. Blog posts on professionalization (n = 51) and communication strategies (n = 27) were also prevalent. Other topics seemed to only appear sporadically throughout the sample. As can be seen in Figure 3, the three most prevalent types of articles were process articles (n = 60), argument (n = 54), and how-to (n = 52). As a reminder, Appendix, Table A provides descriptions for all of the variables and coding categories. Finally, we coded each article to determine the temporal nature of the articles to understand whether blogs were backward looking, present looking, or forward looking. We found that a majority of articles were about the present (n = 203) with a small number of articles focused on the past (n = 18) and future (n = 14).

To further explore the first set of research questions, we conducted a CA to determine if any specific topics were associated with particular article types. Based on the CA, the two coded variables were significantly associated (X2 = 180.269, p < 0.01). Follow-up analyses revealed three significant relationships. First, communication strategies was closely associated with how-to articles: 40.7% of all communication strategies articles were also how-to articles. Second, professionalization articles were closely associated with argument articles: 52.9% of all professionalization articles were also argument articles. Finally, both articles that were categorized as other in both the topic and the article type category closely corresponded. Figure 4 shows this CA visualization.

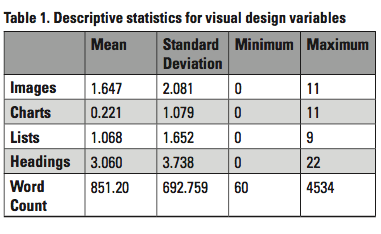

To examine the visual design choices within this sample of blog posts, we counted the number of images, charts and tables, lists, and headings that were present in each blog post. We also recorded word count for each post. Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviation of each of these variables. Also of interest is the wide range of word counts for this sample—the shortest blog post being 60 words and longest being 4,534. This suggests quite a bit of variance in length expectation for this particular genre.

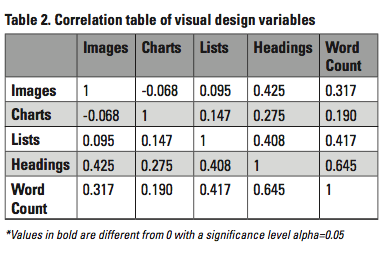

However, examining this data in context provides a more interesting view of the data. Table 2 shows correlations among the visual design variables and reveals a significant and positive correlation between word count and all of the other design elements (headings, images, charts, and lists). A closer look at the data shows a particularly strong correlation between headings and word count and between lists and word count. This seems to suggest that authors of these blog posts are perhaps strategically using visual elements to break up longer chunks of text. We will discuss this in more detail in the discussion section that follows.

However, examining this data in context provides a more interesting view of the data. Table 2 shows correlations among the visual design variables and reveals a significant and positive correlation between word count and all of the other design elements (headings, images, charts, and lists). A closer look at the data shows a particularly strong correlation between headings and word count and between lists and word count. This seems to suggest that authors of these blog posts are perhaps strategically using visual elements to break up longer chunks of text. We will discuss this in more detail in the discussion section that follows.

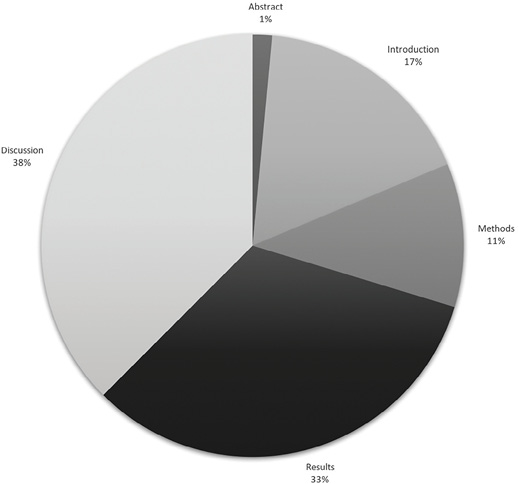

Analyzing research-based blog posts

Our second set of research questions focused on examining how research was presented in our sample of 235 blog posts. First, we wanted to know how often technical communication bloggers actually wrote research blog posts. As a brief reminder, a research blog post was coded as such if the primary content in the blog reported original research or summarized previously conducted research. Based on our analysis, we discovered that the number of research blog posts was quite low—4.25% of all blog posts. We conducted additional coding on these research posts to examine the strategies that authors used while disseminating research findings. First, we identified various sections within a blog post following the well-utilized IMRaD structure. Next, we recorded the number of words that authors used in each of these sections in order to derive a percentage dedicated to each section of the IMRaD structure. Figure 5 provides the average percentage dedicated to each section of the IMRaD structure. As can be seen, on average, the majority of an article was dedicated to the discussion (38%) and results (33%) sections. A much smaller percentage of words was dedicated to the introduction (17%) and even less to the methods (11%). Most of the research blog posts did not include an abstract, which explains the small fraction dedicated to the abstract.

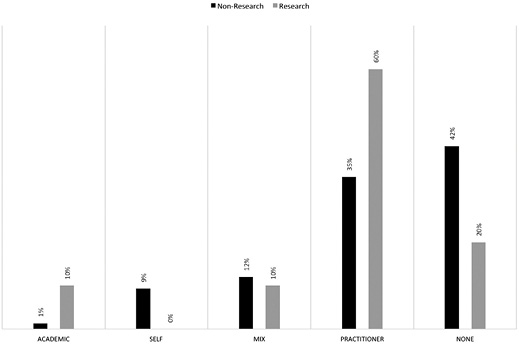

We were also interested in examining the citation practices of technical communication blog authors. As a point of comparison, we analyzed our citation type code for both non-research and research-based blog posts. Figure 6 below shows the relative distribution of citation types comparing non-research and research-based articles. One interesting difference in distributions to note is between academic citations and self-citations. That is, non-research articles tended to rely more heavily on self-citations than did research based articles. On the other hand, research-based blog posts tended to rely more heavily on academic citations than did non-research based blog posts. While these findings are not necessarily surprising, they do indicate some overlap between practitioners and academics in the expectation of the research genre. We will fully discuss the implications of these findings later in the article. In regards to quantity of citation, both non-research (M = 1.594, SD = 2.294) and research-based articles (M = 1.90, SD = 1.792) had a relatively small number of citations. It is important to note, however, that the sample of research posts was small, so we are careful when we draw out implications from these findings.

Finally, we were also interested in how research-based posts might differ from other article types in regards to visual design. To examine these differences, we conducted the Mann Whitney U test to determine whether research articles had more charts than other types of blog posts. We examined charts because we assumed research articles would use charts to display data. We discovered that research articles had significantly more charts than other article types (Mann Whitney U = 2925, p < 0.001). Again, however, we note that the sample size for research posts is relatively small. Therefore, the differences we report here must be hedged and are reported as exploratory results (as opposed to testing a previously held hypothesis).

Examining engagement in practitioner blog posts

Our final set of research questions examined the relative engagement of topics and article types. To examine how a topic influenced engagement, we conducted the Kruskal-Wallis test on topic and three quantitative measures: comments, retweets, and favorites. As a brief reminder, comments were recorded on the blog post itself while retweets and favorites were recorded on the original tweet that shared or announced the blog post. According to the Kruskal-Wallis test, topic significantly influenced comments (X2 (11, n = 235) = 19.80, p = 0.048). However, follow-up pairwise tests using the Dunn-Bonferroni method revealed no significant differences between pairs of topics. The Kruskal-Wallis test also revealed that topic did not significantly influence retweets (p = 0.063). Finally, topic significantly influenced the number of likes that a post received (X2 (11, n = 235) = 25.59, p = 0.007). Since there was significance in the high-level Kruskal-Wallis test, we examined pairwise comparisons using the Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc method, which revealed that communication strategies received significantly more likes than articles on editing and style (adjusted p = 0.043).

We also examined how article type influenced engagement. Based on the results of a Kruskal-Wallis test, article types significantly influenced comments (X2 (7, n = 235) = 23.78, p = 0.001). Follow-up pairwise comparisons using the Dunn-Bonferroni method revealed that argument articles generated the most discussion and produced significantly more comments than news articles (adjusted p = 0.001). How-to articles also produced significantly more comments than did new articles (adjusted p = 0.004). Article type, however, did not significantly influence the number of retweets (p = .34) or likes (p = .07).

Discussion

In the discussion section, we draw out the implications of the results in four major sections. We also specifically discuss how academics might use these results to begin thinking about how to build a shared language for creating conditions that facilitate communication with practitioners.

Academics can connect with practitioners by considering relevant topics

The first step to effectively start a dialogic conversation with practitioners is understanding what they care about, which is revealed through the topics they write about. The top three topics that practitioners wrote about in our sample were technology, professionalization, and communication strategies. Additionally, communication strategies articles were the most engaging as they received significantly more likes than articles on editing and style. This finding echoes Boettger, Friess, and Carliner’s (2014) previous study where they examined the topics and audiences of articles published in Intercom. We explored this result further to learn more specifically what practitioners were blogging about within the technology blog posts. Interestingly, we found that the word DITA was the most frequently used word (n = 27) in the tweets of articles coded as technology, which represented about one-third of all posts on technology. This is particularly interesting because it signifies that practitioners seem to be discussing specific technologies relevant to their practice (e.g., DITA) and not about general software tools (e.g., word processing software). This insight is important to academics as evidenced in a recent blog post about DITA by Tom Johnson, a popular blogger who was responsible for 30 posts in our sample. Tom was discussing an academic article about lightweight DITA published in Technical Communication by Evia and Priestley (2016). Tom expresses his surprise about the relevance and usefulness of the academic article when he writes, “Holy smokes, I never thought I would see Github Pages, Jekyll, and YAML along with my favorite bloggers mentioned in a scholarly tech comm article” (Johnson, 2016). Tom’s sentiment speaks to a divide between practitioners and academics, specifically that “scholarly tech comm” articles almost never examine high-tech (“Github Pages, Jekyll, and YAML”) topics that are relevant to many practitioners. Boettger, Friess, and Carliner’s (2014) study confirms this divide as academics seem to write about topics like rhetoric much more often than topics like technology. More telling in this example, though, is Tom’s reference to Evia and Priestley’s citing of other practitioners. These “favorite bloggers” are part of Tom’s professional community, and the credibility of Evia and Priestley’s research discussion is heightened because it represented these perspectives along with the authors’ academic colleagues. As such, the discussion of Github Pages, Jekyll, and YAML was bridged between academics and practitioners and thus more comprehensively captured the field’s expertise about these technology topics. In summary, Evia and Priestley (2016) do well to speak the language of practitioners and create conditions for facilitating communication with them by 1) writing about topics relevant to practitioners (XML and HDITA) in a practical and direct manner, and 2) citing and studying other practitioners and not just other academics. While this requires self-learning for many, the potential upside of starting a dialogic conversation between academics and practitioners is likely worth it. We do want to point out we are not suggesting that all academic writing must be catered to and/or involve practitioners within the conversation. However, for those in the academic community in technical communication who seek to maintain or bolster relevance, these findings can be helpful in entering into the conversation with practitioners.

Academics can connect with practitioners by considering relevant article types

Another interesting finding was that argumentative articles seemed to generate the liveliest discussion on a blog post, and a CA revealed that argument posts were most often about the professionalization of the field. For example, a post coded as argument and professionalization entitled “The Death of Technical Writing” written by Neal Kaplan (2014) generated by far the most discussion in the entire sample (65 comments on the blog post). Interestingly, the crux of Kaplan’s argument about the changing nature of the field is built around the need to adapt, primarily in being able to create content that is reusable. He even argues that the field has spent too much time focusing on DITA, which he calls “arcane” and “overly complex” (para. 13). Of the 65 comments, many applaud Kaplan’s view of DITA while others come to defend it. Regardless of the outcome of the discussion, practitioners continue to care deeply about the future of the field (Cleary, 2012), a discussion that academics have also been engaging in for decades. To participate in the conversation, academics should consider adding to the discussion by making arguments about the future of the field since practitioners are also interested in this topic.

Additionally, how-to articles were prevalent in the sample, signaling that practitioner audiences value practical information. Our CA revealed a significant relationship between how-to articles and communication strategies, which is particularly interesting because the phrase “how-to” typically connotes rote, task-driven articles about a tool or technology. Our sample, however, revealed that many of our blog authors were writing how-to articles about strategic communication and not about technology. For instance, one article in our sample walks readers through a step-by-step process for implementing a social media strategy into a small business. This finding should encourage academics because it shows that practitioners are not simply interested in articles that help them accomplish simple tasks. Rather, practitioners seem more interested in strategic, yet practical content that they can implement into their work contexts. As such, academics should consider incorporating how-to type articles for practitioner audiences when appropriate. For instance, IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication publishes peer-reviewed tutorial articles that are focused on issues related to high-level, strategic communication. Killoran (2013), for instance, published a tutorial article about search engine optimization, which was clearly directed at practitioner audiences. Similarly, Baehr (2012) published a tutorial on how to apply theoretical models, such as media richness, to e-learning modules. These articles are unique in that they retain academic rigor while still being relevant to practitioner audiences. Besides writing full-blown tutorial articles, academics can also consider incorporating aspects of how-to articles into their existing academic research agendas by explicitly describing how their work contributes to both theory and practice, much like is done in the practitioner takeaway section in articles published in the journal Technical Communication.

Academics can connect with practitioners by modeling their research reporting and citation style

When research was reported, practitioners seemed to emphasize results and discussion over detailed descriptions of what motivated their research (e.g. the introduction and their methods). As such, practitioners are directing little attention to fleshing out the research space or justifying the method they followed to generate findings. Generally speaking, academics need to flesh out research space to defend against criticism and establish the exigency of a study. It seems, though, that practitioners are not constrained in the way academics are in regards to reporting research. Therefore, an immediate implication of practitioners’ research dissemination is the need for academics to be aware of the publishing environment in which practitioners share knowledge. To join the conversation with practitioners, academics could allow themselves to model this dissemination pattern in their own reporting of research. We are not suggesting that academics should stop reporting their methods or writing literature reviews, but we are suggesting that academics consider foregrounding findings and practical implications whenever possible. Specifically, academics could write and share brief summaries of results from larger research projects that are accessible and practical for practitioners disseminated on personal blogs, university websites, and other non-traditional venues that are accessible to practitioners and do not require access to an academic journal database.

Another interesting characteristic of practitioner research blog posts was their citation patterns. For non-research blog posts, practitioners most often cited other practitioners and themselves. In research-based blog posts, they most often cited other practitioners and academics but never cited themselves. These patterns of citation make us consider two interesting points. First, practitioners seem to know the work of their colleagues and value creating a network of knowledge sharing in their blogosphere. In that sense, their citation is not very different than academics at all. Second, practitioners seemed to change their citation patterns when reporting research—most notably in the lack of self-citation. Perhaps practitioners are establishing credibility by linking to and citing external sources in their desire to make the research they discuss more credible. The shift in citation style is telling in how it signals practitioners’ efforts to align their citation practices to academics’ citation practices in research articles. To reciprocate this effort, academics might consider, when appropriate, adapting their citation practices to align with practitioners’ citation practices in both research and non-research articles. For instance, academics who write about technology, professionalization, or communication strategies could consider citing practitioners to begin a dialogic conversation. That is, practitioners are on the ground experiencing angst related to professionalization, implementing new communication strategies, and using new technology, and therefore have much to say regarding these topics. Furthermore, citing practitioners in academic work can and should be mutually beneficial. First, it gives a voice to and validates practitioners, which of course benefits practitioners. Second, it can make academic work more visible in the practitioner community, which benefits academics by providing opportunities to apply and test academic theories and ideas in a real-world context. This symbiotic citation style is a way to establish an ongoing conversation among practitioners and academics.

Academics can connect with practitioners by blogging

Finally, we want to end the article by picking up on Davis’ (2013) call and encourage academics to engage and collaborate with practitioners by participating in the practitioner blogosphere. While we realize there are many good reasons not to blog (time constraints, tenure considerations, not wanting to give away results before they are published), academics must consider that one reason for the academic/practitioner divide could be that we are simply not having the conversation in the right way, in the right place, at the right time. Engaging with practitioners in the genre they are most familiar with is a significant and obvious way to encourage conversations among academics and practitioners. Our study revealed several strategies that academics might consider when blogging. For example, since practitioners tended to use more visuals (graphs, charts, and tables) as word count increased, academics should consider strategically using visual elements to accommodate blog readers’ expectations. Additionally, our study found that the average length of blog posts was about 850 words. So, to accommodate practitioners’ expectations, academics should be concise and report the most actionable and practical information. In both of these examples, we are encouraging academics to employ shared language or the dissemination patterns that are used and valued by practitioners. One author of this study has, perhaps unsuccessfully, begun blogging and sharing research results. While the conversation has not initiated any paradigm shifts in the field, it is a start that we hope continues.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There were two primary limitations of the study. First, the sample size of research posts was small and therefore restricted the statistical analysis we conducted. While we had no control over the number of research posts within the sample, a future study could search more explicitly for research-based practitioner blog posts. Additionally, a follow-up study could dive deeper into research blog posts using a qualitative method like discourse or genre analysis. A second limitation of the study was the way in which we coded for engagement. We counted the number of comments each post received, which provides a quantitative engagement metric. However, a future study could examine these comment threads qualitatively to get a sense of the types of conversations that certain blog posts generate.

Ultimately, we hope this study sheds light on practitioner knowledge sharing practices and provides practical pathways for academics to work toward developing shared language with practitioners, when appropriate, and thus be in a position to engage in more dialogic conversation with our industry counterparts. We also hope that this study will be helpful for academics to begin considering the relevancy of our research questions to practitioners and the subsequent communication of research results to practitioners. As a way to begin assessing the relevancy of our research questions to practitioners, academics can begin using blogs to guide the development of our research questions using language from practitioner conversations.

References

Albers, M. (2015). Call for Submissions for Special Issue of Technical Communication: “Communication of Research Between Academic and Practicing Professionals.”

Austin, W., Park, C., & Goble, E. (2008). From interdisciplinary to transdisciplinary research: A case study. Qualitative Health Research, 18(4), 557–564.

Baehr, C. (2012). Incorporating user appropriation, media richness, and collaborative knowledge sharing into blended e-learning training tutorial. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 55(2), 175–184.

Blythe, S., Lauer, C., & Curran, P. G. (2014). Professional and technical communication in a web 2.0 world. Technical Communication Quarterly, 23(4), 265–287.

Boettger, R. K., & Lam, C. (2013). An overview of experimental and quasi-experimental research in technical communication journals (1992–2011). IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 56(4), 272–293.

Boettger, R. K., & Palmer, L. A. (2010). Quantitative content analysis: Its use in technical communication. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 53(4), 346–357.

Boettger, R. K., Friess, E., & Carliner, S. (2015, July). Update to who says what to whom? Assessing the alignment of content and audience between scholarly and professional publications in technical communication (1996–2013). In Professional Communication Conference (IPCC), 2015 IEEE International (pp. ١–6). IEEE.

Boettger, R. K., Friess, E., & Carliner, S. (2014, October). Who says what to whom? Assessing the alignment of content and audience between scholarly and professional publications in technical communication (1996–2013). In Professional Communication Conference (IPCC), 2014 IEEE International (pp. 1–6). IEEE.

Bracken, L. J., & Oughton, E. A. (2006). ‘What do you mean?’ The importance of language in developing interdisciplinary research. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 31(3), 371–382.

Brescia, W. F., & Miller, M. T. (2006). What’s it worth? The perceived benefits of instructional blogging. Electronic Journal for the Integration of Technology in Education, 5(1), 44–52.

Bridgeford, T., & St.Amant, K. (2015). Academy-Industry relationships and partnerships: Perspectives for technical communicators. Amityville, NY: Baywood Publishing Company.

Brumberger, E., & Lauer, C. (2015). The evolution of technical communication: An analysis of industry job postings. Technical Communication, 62, 224–243.

Carliner, S., Legassie, R., Belding, S., MacDonald, H., Ribeiro, O., Johnston, L., & Hehn, H. (2009). How research moves into practice: a preliminary study of what training professionals read, hear, and perceive. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology/La Revue Canadienne de l’Apprentissage et de la Technologie, 35(1).

Chai, S., Das, S., and Rao, R. (2011). Factors affecting bloggers’ knowledge sharing: An investigation across gender. Journal of Management Information Systems, 28, 309–342.

Chiu, C. M., Hsu, M. H., & Wang, E. T. (2006). Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decision support systems, 42(3), 1872-1888.

Cleary, Y. (2012). Discussions about the technical communication profession: Perspectives from the blogosphere. Technical Communication, 59, 8–28.

Cooke, L., & Mings, S. (2005). Connecting usability education and research with industry needs and practices. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 48, 296–312.

Coon, A. C., & Scanlon, P. M. (1997). Does the curriculum fit the career? Some conclusions from a survey of graduates of a degree program in professional and technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 27, 391–399.

Davis, M. T. (2013, July). Finding common ground as we cross borders. In IEEE International Professional Communication 2013 Conference (pp. ١–4). IEEE.

Dunn, O. J. (1964). Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics, 6(3), 241–252.

Evia, C., Tech, V., & Priestley, M. (2016). Structured authoring without XML: Evaluating lightweight DITA for technical documentation. Technical Communication, 63, 23–37.

Hannah, M. A., & Saidy, C. (2014). Locating the terms of engagement: Shared language development in secondary to postsecondary writing transitions. College Composition and Communication, 66, 120–144.

Henschel, S., & Meloncon, L. (2014). Of horsemen and layered literacies: Assessment instruments for aligning technical and professional communication undergraduate curricula with professional expectations. Programmatic Perspectives, 6(1), 3-26.

Hillan, J. (2003). Physician use of patient–centered weblogs and online journals. Clinical Medicine & Research, 1(4), 333–335.

Hinrichs, L., & White-Sustaíta, J. (2011). Global Englishes and the sociolinguistics of spelling: A study of Jamaican blog and email writing. English World-Wide, 32(1), 46–73.

Hsu, C. L., & Lin, J. C. C. (2008). Acceptance of blog usage: The roles of technology acceptance, social influence and knowledge sharing motivation. Information & Management, 45(1), 65–74.

Johnson, T. (2016, Feb. 23). Lightweight DITA article in technical communication journal. Retrieved from http://idratherbewriting.com/2016/02/23/lightweight-dita-hdita-model/

Kaplan, N. (2014, May 3). The death of technical writing, part 1. Retrieved from https://customersandcontent.com/2014/05/03/the-death-of-technical-writing-part-1/

Killoran, J. B. (2013). How to use search engine optimization techniques to increase website visibility. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 56, 50–66.

Lagu, T., Kaufman, E. J., Asch, D. A., & Armstrong, K. (2008). Content of weblogs written by health professionals. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23, 1642–1646.

Lam, C. (2016). Correspondence analysis: A statistical technique ripe for technical and professional communication researchers. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59, 299–310.

Lam, C., & Hannah, M. A. (2016a). Flipping the audience script: An activity that integrates research and audience analysis. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 79, 28–53.

Lam, C., & Hannah, M. A. (2016b). The social help desk: Examining how Twitter is used as a technical support tool. Communication Design Quarterly Review, 4(2), 37–51.

Lam, C., Hannah, M. A., & Friess, E. (2016). Connecting programmatic research with social media: Using data from Twitter to inform programmatic decisions. Programmatic Perspectives, 8(2), 47–71.

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 159–174.

Lanier, C. R. (2009). Analysis of the skills called for by technical communication employers in recruitment postings. Technical Communication, 56, 51–61.

Lesser, E. L., & Storck, J. (2001). Communities of practice and organizational performance. IBM Systems Journal, 40(4), 831.

Maag, M. (2005). The potential use of “blogs” in nursing education. Computers Informatics Nursing, 23(1), 16–24.

Makri, K., & Kynigos, C. (2007). The role of blogs in studying the discourse and social practices of mathematics teachers. Educational Technology & Society, 10(1), 73–84.

Mamykina, L., Candy, L., & Edmonds, E. (2002). Collaborative creativity. Communications of the ACM, 45(10), 96–99.

Milligan, R. A., Gilroy, J., Katz, K. S., Rodan, M. F., & Subramanian, K. S. (1999). Developing a shared language: Interdisciplinary communication among diverse health care professionals. Holistic Nursing Practice, 13(2), 47–53.

Mynard, J. (2008). A blog as a tool for reflection for English language learners. The Philippine ESL Journal, 1, 77–89.

Rainey, K. T., Turner, R. K., & Dayton, D. (2005). Do curricula correspond to managerial expectations? Core competencies for technical communicators. Technical Communication, 52, 323–352.

Spilka, R. (2009). Practitioner research instruction a neglected curricular area in technical communication undergraduate programs. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 23, 216–237.

Thrush, E. A., & Hooper, L. (2006). Industry and the academy: How team-teaching brings two worlds together. Technical Communication, 53, 308–316.

Watson, J., M. S. N. (2012). The rise of blogs in nursing practice. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 215–217.

Whiteside, A. L. (2003). The skills that technical communicators need: An investigation of technical communication graduates, managers, and curricula. Journal of TechnicalWriting and Communication, 33, 303–318.

Yang, S. H. (2009). Using blogs to enhance critical reflection and community of practice. Educational Technology & Society, 12(2), 11–21.

Yang, C., & Chang, Y. S. (2012). Assessing the effects of interactive blogging on student attitudes towards peer interaction, learning motivation, and academic achievements. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28(2), 126–135.

About the Authors

Mark A. Hannah is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at Arizona State University. He teaches courses in professional communication, technical communication, and business communication. His research has appeared in Technical Communication Quarterly, Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, Communication Design Quarterly, Connexions International Professional Communication Journal, Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, International Journal of Business Communication, Programmatic Perspectives, College Composition and Communication, and chapters in edited collections. He is available at mark.hannah@asu.edu.

Chris Lam is an Assistant Professor of Technical Communication at the University of North Texas. He researches team communication, professionalization issues in technical communication, and applications of social media to technical and professional communication. He’s published in Journal of Business and Technical Communication, Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, International Journal of Business Communication, Communication Design Quarterly, Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, and Programmatic Perspectives. He is available at chris.lam@unt.edu.

Manuscript received 2 May 2016; revised 5 August 2016; accepted 10 August 2016.

Appendix