Abstract

Purpose: Technical communication research should link the academy to industry and sustain both with a foundation for solving problems and identifying new areas of inquiry. However, the publication needs and motivations of academics and practitioners have resulted in content alignment issues so divergent that it oftentimes appears that both parties are from different planets.

Method: We empirically analyzed the content within 1,048 published articles over a 20-year period within core professional and academic forums. We coded the articles for variables related to topic and audience. Data were analyzed through descriptive statistics and correspondence analysis.

Results: Our field’s core content forums have evolved little over the last 27 years. Results also indicated distinct differences in article topics and audience that reflect the varying interests of academics and practitioners. Intercom and Technical Communication Quarterly emerged as the most defined forums.

Conclusion: The incongruity within professional and academic articles further suggests that we are a fragmented discipline. We recommend that our current content forums adopt structured abstracts and implications statements to unify our research and that researchers seek alternative audiences for their scholarship. We also call on practitioners to strengthen their involvement in research, either by contributing to scholarship or by volunteering their organizations as research sites.

Keywords: academy-industry relationship, content analysis, correspondence analysis, research, technical communication

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Professional forums align with scholarly forums on content topics, such as genre, communication strategies, collaboration, intercultural communication, and usability and user experience.

- Professional forums also differ from scholarly forums. Intercom frequently produces process- and profession-oriented content as well as content on professionalization, technology, and editing and style, which benefit a variety of audiences, including writer/content developers, generalists, senior writers, and managers.

- Practitioners need to invest more in the field’s research. We call on practitioners to contribute more to scholarship or volunteer their organizations as research sites. Solid practitioner-focused research answers compelling questions that can have a strong indirect value in preserving jobs and increasing salaries.

Ideally, academics should feed off of information provided by practitioners, and practitioners should thrive based on the research published by academics. The two groups can mutually benefit each other. In reality, however, practitioners and academics often live on two different planets, with little interaction or contact between the worlds. (Tom Johnson, “I’d Rather Be Writing,” August 5, 2015)

A continuing conversation in technical communication is the relationship between the academy and industry. For over 30 years, one specific conversation involves the palpable academy-industry divide when it comes to the research of the field (Boettger, Friess, & Carliner, 2014; Bridgeford & St.Amant, 2015; Carliner, 1994; Goubil-Gambrell, 1998; Kimball, 2015; Pinelli & Barclay, 1992; F. R. Smith, 1985, 1992; St.Amant & Meloncon, 2016). Our study extends this conversation with an empirical content analysis of 1,048 technical communication articles published over a 20-year period. Understanding the content alignment (or lack thereof) among academics and practitioners inventories our past and facilitates our future.

Research links the academy to industry and sustains both with a foundation for solving problems and identifying new areas of inquiry (Goubil-Gambrell, 1998). Smith’s (2000a, 2000b) analyses of technical communication forums between 1988 and 1996 provided an important perspective on the strength and diversity of the journals and serials that published our field’s conversations. Smith concluded both her pieces with optimism; by 1988, a handful of journals offered the necessary and diverse forums to advance technical communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication (JBTC) and Technical Communication Quarterly (TCQ) were identified as significant forums for academic conversations and tenure and promotion purposes. In particular, TCQ’s evolution from Technical Writing Teacher (TWT) reflected the overall scholarly maturity of technical communication. Conversely, Technical Communication (TC) and IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication (TPC) were publishing research and theoretical discussions from the vantage of practitioners. The professional publication Intercom extended this diversity, evolving from a newsletter to a magazine that could respond to current practitioner issues with efficiency and accessibility.

Yet, when technical communication transitioned into the 21st century, some of the optimism related to the applicability and impact of this research appeared to fade. Kynell and Tebeaux (2009) questioned whether our research was truly having its intended impact with industry and outside disciplines and not instead just fulfilling tenure and promotion purposes. They directed readers to answer a series of questions, including, “Are we [academics] talking only to and among ourselves? . . . Are we writing to gain tenure and promotion, as well as legitimacy in academe, or do we want to make a difference in the practice of technical communication? Whom are we trying to reach? Who are our audiences?” (p. 139).

Some of these questions have been explored. Recently, St.Amant and Meloncon (2016) wrote that discussions to bridge the academy and industry primarily occur within our existing forums and, thus, mainly among academics. This creates what they labeled an “incommensurability” problem that fragments rather than unifies technical communication. Further, it has been observed that practicing technical communicators recognize the need for research but do not always find much of what the academy produces as valuable (Goubil-Gambrell, 1998). Tom Johnson (2015, August 5 ), a technical writer and creator of the blog “I’d Rather Be Writing,” wrote that “practitioners and academics often live on two different planets, with little interaction or contact between the worlds” (para. 6). Blogger Danielle M. Villegas (2015, July 20) offered a similar notion, observing that practitioners and academics share a common goal in evolving the field and training the best communicators. “How can we go wrong with a goal like that?” (para. 11) she questioned.

These types of conversations are paramount to disciplines that speak to both academics and professionals. For example, fields like education and management have empirically explored the extent to which research from the academy moves into practice. Studies in these areas found that although practicing professionals have an interest in research, few regularly read research articles (Carliner et al., 2009; Lysenko, 2010). Similarly, management researchers found that managers were only familiar with about two-thirds of research-validated practices in their field (Rynes, Colbert, & Brown, 2002).

Additionally, other researchers across disciplines have sought to understand the extent of alignment between researchers and professionals. Deadrick and Gibson (2007) analyzed leading academic journals and profession magazines within a sub-discipline of human resources management to generate their conclusions. They found that the two publication types focused on different topics and concluded that researchers and practicing professionals had different interests.

Although many studies have explored opinions about the alignment between technical communication academics and practitioners, few studies have attempted to empirically assess this alignment. In this paper, we report the results of a content analysis on the leading technical communication content forums. Our study was designed around the following research questions:

RQ1. How is content broadly classified across these articles?

RQ2. What are the primary content areas covered in these articles?

RQ3. Who are the primary audiences that would benefit most from this content?

The paper has the following structure. The methods section describes how the study was conducted, beginning with identifying the sample and followed by describing the measures used to explore the sample. The results section reports the content characteristics we identified in five technical communication content forums (four journals and one profession magazine). We examine how our results contribute to the field’s body of knowledge and conclude with a series of calls to action for both academics and practitioners.

Methods

To address our research questions, we conducted a content analysis in the vein of the study of human resources management articles by Deadrick and Gibson (2007). Content analyses assess words, phrases, or relationships in texts. We define the method as “a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (and other meaningful matter) in the contexts of their use” (Krippendorff, 2012). Similarly, we apply content analysis quantitatively, which includes identifying meaning through valid measurement rules and making relational inferences with statistical methods (Boettger & Palmer, 2010). The general framework for quantitative content analysis includes identifying the sample, developing a coding scheme, norming raters, and analyzing data.

Our sample included 1,048 articles published within five forums over a 20-year period (1996–2015). This sample was randomly selected from a population of 3,605 articles. Therefore, we coded almost 30% of the population, providing a 95% confidence level (±3).

We inventoried and numbered the population in an Excel worksheet and then identified the sample with the software’s random number generator. The population included every peer-reviewed article in the four leading technical communication journals and every feature article and column in the profession magazine Intercom. Our forum selections included JBTC, TC, TCQ, and TPC, which were previously identified as the leading scholarly forums in the field (Carliner, Coppola, Grady, & Hayhoe, 2011; Lowry, Humpherys, Malwitz, & Nix, 2007; E. O. Smith, 2000b). We selected Intercom, the longest published magazine in the field, to contrast the scholarly articles. Intercom began as a newsletter in 1953 with the founding of the predecessor organization to its publisher, the Society for Technical Communication. The organization began publishing it as a magazine in January 1996. Therefore, we began our analysis timeframe in 1996, when all five forums were producing content. We concluded the timeframe in 2015, which, at the time of coding, provided the latest complete volume of each journal. Intercom published 53% of the content in the sample (n = 522 articles) and the four journals published 47% of the content (JBTC = 102, TC = 115, TCQ= 127, and TPC = 150).

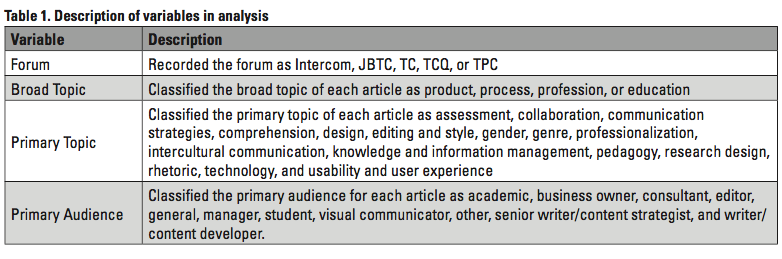

Once we captured the sample, we coded the 1,048 articles for four content variables: forum, broad topic, primary topic, and primary audience. Table I provides a description of each variable and its levels. Few instruments exist for categorizing technical communication content. To create the codebook, we first identified variables used in previous, similar studies (Boettger & Lam, 2013; Carliner et al., 2011). Over six norming sessions, three raters used an independent sample of articles to test and refine the coding categories.

For mutual exclusivity purposes, we coded each variable for its primary focus. For example, the primary topic of an article on a collaborative model for teaching international engineering students about the language and culture of a foreign research environment could be classified as collaboration, pedagogy, or intercultural communication. However, the article’s primary focus is pedagogy, so it was coded as such. Similarly, primary audience was coded based on who would most benefit from reading the content rather than who was most likely to read it. This approach assisted in the norming of raters and inter-rater reliability. The codebook went through 10 drafts before it was applied to the actual sample. Contact the researchers for a copy of the codebook used for this study.

Over 10 coding sessions, three raters coded the sample reported in the present study; 20% of the sample was re-coded for reliability purposes. After each session, the raters would discuss any between-rater discrepancies to better inform the next coding session. (See [Boettger et al., 2014] for a description of the preliminary codebooks and initial norming sessions.) Inter-rater reliability was calculated with Krippendorff’s alpha coefficient. We calculated variables independently rather than collectively—forum (100% agreement), broad topic (80.2%), primary topic (82%), primary audience (76%)—which were all in the recommend range (Watt & van den Burg, 1995).

We analyzed the data through descriptive statistics and correspondence analysis. Correspondence analysis (CA) is a geometric technique used to analyze two-way and multi-way tables containing some measure of correspondence between the rows and columns (Greenacre, 2007). The approach provides results that are comparable to Principal Components Analysis or Factor Analysis but is designed for non-numeric data. The application of CA has grown in technical communication scholarship in recent years (Boettger & Lam, 2013; Lam, 2014). Due to its exploratory approach, CA is not a method used to test hypotheses. Instead, it reveals patterns in complex data and provides output that can help researchers interpret these patterns. The most useful component of CA is its ability to visually organize the data in the categories into central and peripheral instances. The increasing distance of any representative of either category from the origin corresponds to a higher degree of differentiation as compared with the other members with respect to their co-occurrences with the data in the other category.

Results

This section organizes the results around the three research questions.

RQ1. How is content broadly classified across these articles?

Over 36% of the sample were articles classified as process-oriented and 33% were classified as product-oriented. Process articles focused on a part or all of the tasks involved in producing and delivering a product. Intercom published more of these publication types than the journals (n = 215, 167). Product articles focused on a characteristic of some or all of a service or a deliverable. The journals collectively published more of these article types than Intercom (n = 193, 156).

The remaining articles were either profession-oriented (18%), characterizing some aspect of the identity of a technical communicator, or education-oriented (13%), focusing on education and training for technical communicators. Intercom published more process-oriented articles than the journals (n = 159, n = 25), and the journals published more education-orientation articles (n = 112, n = 22).

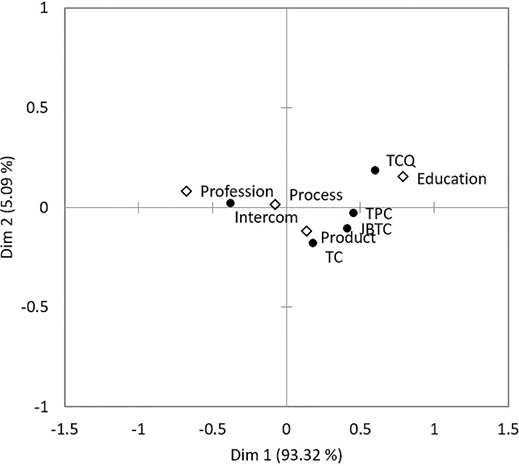

To further examine the relationship between forum and broad topic, we conducted a correspondence analysis (CA). CA is not an inferential measure and therefore does not determine statistical significance. The statistical output provides a chi-square value, but this value relates to the overall interaction between the rows and columns; it is up to the researcher to consult other statistical output to properly interpret the results. Throughout this section, we report only CAs that had a significant chi-square value of ≤ 0.05, but we reviewed other output to determine between-variable relationships. Additional output included the eigenvalue for each correspondence, which determines how accurately the two-dimensional visualization explains the variation, as well as the quality score and inertia of the data.

There was a significant relationship between forum and broad topic (χ2 = 188.587 p < 0.0001). Based on the statistical output, three associations were revealed (see Figure 1).

The strongest association was found between Intercom and articles broadly classified as profession. These types of articles focused on how technical communicators perceived their role in the field, including how the role and skillsets of technical communications have evolved as well as efforts to earn respect from third parties. This broad topic represented 28.80% of the broad topics coded for Intercom. The author in one of the earliest articles in the sample problematized the question, “what is professionalism?,” and called on technical communicators to be responsible for their work in order to gain recognition from third parties (DuBay, 1996). The evolution of technical communicators is suggested with one of the more recent pieces in the sample, where the author describes how she transferred her technical communication skillset to a marketing position (Ronning-Hall, 2012).

The next association was found between TCQ and education. These types of articles addressed how academics prepared the next generation of technical communicators. This broad topic represented 34.65% of the topics coded for TCQ. An early example from the sample included an analysis of how an academic veterinary scientist engaged with professional writing and how those experiences related to technical writing pedagogy (Lott & Barrett-O’Leary, 1996). One recent piece in the sample encouraged academic technical communication programs to deploy rhetorical performance portfolios and memory inventories to enable students to express their value in the workplace (Brady & Schreiber, 2013).

The final association was found between TC and product. These types of articles addressed what technical communicators produce, including some or all of a service or a deliverable (any finished product). This broad topic represented 41.74% of the topics coded for TC. An early example from the sample included concept mapping as a job performance aid for writers of technical documents (Crandell, Kleid, & Soderston, 1996). One recent example describes a bottom-up method for designing effective materials for international audiences using a mobile application (Lauren, 2015).

RQ2. What are the primary content areas covered in these articles?

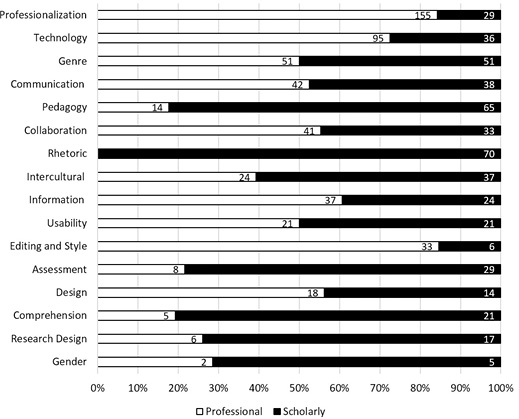

Our codebook included 16 primary topics. Almost 40% of the sample consisted of articles on professionalization, technology, or genre (18%, 13%, and 10%, respectively). As illustrated by Figure 2, professionalization and technology content were found most often in Intercom; however, genre content was equally distributed within Intercom and the four journals. Content on pedagogy, rhetoric, assessment, comprehension, and design were published in the four journals with more frequency than Intercom. Rhetoric was the only topic exclusive between forums and identified only in the scholarly journals.

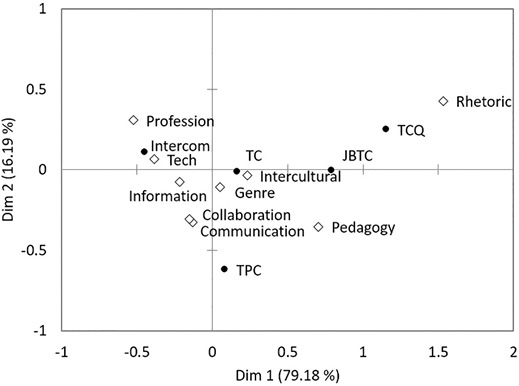

We conducted a second CA to examine the relationship between forum and primary topic. Due to sample size, we only analyzed the nine most frequent topics. There was a significant relationship between the variables (χ2 = 358.136 p < 0.0001). Based on the statistical output, three associations were revealed (see Figure 3).

The first association was between Intercom and professionalization. Texts coded as professionalization included discussions of professionalization issues in technical communication as well as narratives that describe the history or current state of technical communication programs and practices. This primary topic represented 33.77% of the topics coded for Intercom. Examples include the earlier cited articles (DuBay, 1996; Ronning-Hall, 2012) as well as the “My Job” columns in Intercom, which discussed the skillsets important to technical communicators like storytelling (Raymond, 2012) or how technical communication was used in specific careers, such as rail transportation (Beaudin-Hayes, 2008).

Next, TCQ was associated with rhetoric. Texts coded as rhetoric presented a theoretical or philosophical examination with the primary objective of pursuing theory rather than applying theory and knowledge (Goubil-Gambrell, 1998; Kynell & Tebeaux, 2009). This primary topic represented 36.63% of the topics coded for TCQ. Examples from the sample included a rhetorical analysis of stakeholders in environmental education (Coppola, 1997) as well as the use of the ironic delivery sites of rhetorics surrounding the Deepwater Horizon disaster (Frost, 2013).

Finally, TPC was associated with pedagogy. Texts coded as pedagogy discussed how specific learning strategies impact students’ communication practices. This primary topic represented 19.17% of the topics coded for TPC. Examples from the sample included the application of Systemic Functional Linguistics to introduce international engineering students into the language and culture of a research environment (McGowan, Seton, & Cargill, 1996) as well as the use of the communication model framework to teach students evidence-based writing through corporate blogs (Lee, 2013).

RQ3. Who are the primary audiences that would benefit most from this content?

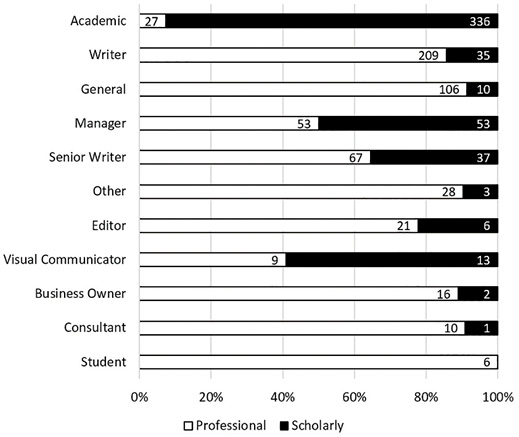

Our codebook included 11 primary audiences, and we coded this variable based on who would most benefit from reading the content rather than who was most likely to read it. Overall, our results showed that 35% of the content would most benefit academics, who were defined as instructors or researchers in accredited academic institutions. An additional 23% of the sample were classified as writer/content developers, who were defined as those who typically write and produce technical content on assignment. Perhaps not surprisingly, 67.7% of the primary audience for the journals were academics, followed next by managers (10.69%). In contrast, Intercom demonstrated more disparity; writer/content developers were the largest audience (37.86%), but generalists (19.20%), senior writer/content strategists (12.14%), and managers (9.60%) were also well represented. Students were the only audience exclusive to one forum and identified only in Intercom (see Figure 4).

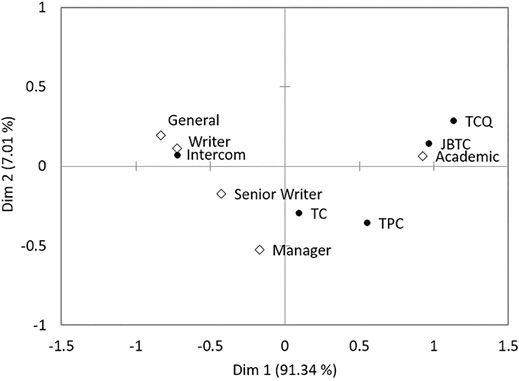

We conducted our final CA to examine the relationship between forum and primary audience. Due to sample size, we only analyzed the five most frequently identified audiences. There was a significant relationship between the variables (χ2 = 592.876 p < 0.0001). Based on the statistical output, four associations were revealed (see Figure 5).

The first association was between Intercom and the writer/content developer. This audience was defined as those who typically write and produce technical content on assignment. This primary audience represented 45.24% of the audience types coded for Intercom. Early examples from the sample included articles on Usenet newsgroups, CD-ROMS, and clipart (Kovner, 1998; Lindgren, 1996; Menz, 1997). More recent examples included articles on measuring information architecture value, content delivery through eBooks, and agile best practices for technical writers (Demback, 2015; Prentice, 2014; Trunzo & De Vries, 2012).

The next two associations were found between JBTC and the academic as well as between TCQ and the academic. This audience was defined as instructors or researchers in accredited academic institutions. This primary audience represented 86.41% of the audience types coded for JBTC and 96% for TCQ. Early examples from the sample included articles on teaching American business writing in Russia (Hagen, 1998) and on the evaluation of qualitative inquiry in technical communication (Blakeslee, Cole, & Conefrey, 1996). More recent examples included discussion of how early yellow fever maps invoked power and authority over diseased space through their visual conventions and scientific authority as statistical graphics (Welhausen, 2015) as well as investigations of the social justice implications of locations and results (Agboka, 2013).

The final association was between TC and manager. This audience was defined as someone charged with producing and delivering a body of content to the sponsor by the specified deadline, within a specified budget, and at the specified level of quality. The manager is also legally culpable for a potential liability or violation of ethics. This primary audience represented 16.33% of the audience types coded for TC. Examples included articles on how to manage the effects of organizational change, the measure of productivity and effectiveness, and how technical communicators transition into the role of manager (Bottitta, Idoura, & Pappas, 2003; Carliner, Qayyum, & Sanchez-Lozano, 2014; Scott, 1996).

Discussion

We analyzed the content alignment (or lack thereof) among leading technical communication forums. We coded 1,048 published articles from four technical communication journals and the professional magazine Intercom on four variables. In this section, we discuss those results and their relevancy to previous research.

Overall, the professional magazine Intercom produced more process- and profession-oriented articles, and the four scholarly journals collectively produced more product- and education-oriented articles. Both forums published about an equal amount of articles on genre, communication strategies, collaboration, intercultural communication, and usability and user experience, suggesting some alignment. Content differences were also identified; Intercom produced substantively more on professionalization, technology, and editing and style, but the journals produced more on pedagogy, rhetoric, assessment, comprehension, and research design. Finally, Intercom publications were found to benefit a variety of primary audiences, particularly writers and content developers. Conversely, the journals were found to primarily benefit academics.

Results also identified defined differences between each publication forum, echoing findings from earlier research. Intercom and TCQ emerged as the most defined forums in technical communication. Intercom corresponded to the broad topic of profession, the primary topic of professionalization, and the primary audience of writer/content developer. TCQ corresponded to the broad topic of education, the primary topic of rhetoric, and the primary audience of academic. TC was the third most defined publication forum, corresponding to product-oriented articles and managers. Finally, TPC corresponded to the primary topic of pedagogy, and JBTC to academics. Each forum appeared to serve a specific need to technical communicators, which journal editors, prospective authors, and practitioners should note for their various purposes.

Perhaps the most compelling finding in this study, however, is that the content forums we analyzed are fulfilling the same needs they did in 1988. Smith’s (2000ab) analyses of technical communication forums concluded with optimism about the direction of research that would speak to both academics and practitioners. On one hand, the continuation of these content areas might reflect stabilization. Our research topics and approaches indicate that technical communication is at the intersection of a host of other fields (such as writing studies, psychology, human factors, and engineering), and this interdisciplinary breadth has historically been identified as one of our strengths. Technical communication has long grappled with issues of identity, professionalization, status, and legitimacy (Carliner, 1994, 2012; Selber, 1998; St.Amant & Meloncon, 2016). The fact that our general content areas and forums have remained unchanged for almost 30 years may indicate the solidification of the core attributes of the field.

On the other hand, the amount of defined differences within our forums when compared to the size of our field could be symptomatic of the field’s identified fragmentation. Instead of providing core attributes, these differences could contribute to the “incommensurability” problem that St.Amant and Meloncon (2016) described, and “with so many disparate parts and varying areas of study,” it is difficult to “come together to create a coherent, and thus, a legitimate field” (p. 3).

We should also question how the topics that correspond to our existing forums inform our future. In our study, rhetoric was the sixth most popular primary topic and the only topic exclusive to the scholarly forums. Rhetoric should inform technical communication, but rhetoric, when explored in the abstract, is not technical communication. Our research should ideally apply rhetorical strategies to offer thorough explanations of technical communication processes and provide strategies for developing related products. If we want to continue producing content that highlights rhetorical agency or postplural rhetoric of science as the objects of study rather than the facilitators of new knowledge, we should also consider if outside forums are more appropriate for these inquiries. Further, former strongholds of technical communication, such as usability and content strategy, now have robust presences outside our current forums. New forums like Communication Design Quarterly, Journal of Usability Studies, and Journal of Writing Research are being edited by and (or) well contributed by technical communicators. We might not collectively consider these journals as primary forums for our research, yet they provide the same competitive acceptance rates as our core forums in addition to interdisciplinary editorials scopes, international readership, and open-access appeal. We are even ceding the authorship within our core forums; recent authors are not likely to hold a doctoral degree in technical communication. A healthy population of authors are also housed in information systems and technology departments or management, business, and economics departments (Lam, 2014). These outside disciplines have significant influence in shaping the field, perhaps introducing another contributor to the earlier-noted incommensurability problem.

These movements come at a time when scholars are also questioning the impact of their own research. It has been suggested that some of our current forums often function as repositories for tenure and promotion materials (Goubil-Gambrell, 1998; Kynell & Tebeaux, 2009), vital to the sustainability of technical communication but perhaps not focused enough on the shared interests of the field (St.Amant & Meloncon, 2016). There is also evidence that professionals, including some who formulated the theories on which our field is based, no longer attend our conferences or participate in our professional organizations (Carliner, 1994). Additionally, the number of critical voices in technical communication have steadily increased as well as the growth in research that not only examines what we produce, but how well it is produced (Blakeslee, 2009; Boettger & Lam, 2013; Boettger & Palmer, 2010; Carliner et al., 2011; Coppola & Carliner, 2011; Lam, 2014; McNely, Spinuzzi, & Teston, 2015; St.Amant & Meloncon, 2016). Collectively, these results suggest a series of actions related to content alignment that all technical communicators should consider moving forward.

Calls to Action

In this final section, we present three calls to actions that address the alignment issues in technical communication: 1) unify existing forums, 2) identify new audiences, and 3) engage practitioners in research.

Unify existing forums

If technical communicators accept that our field is fragmented, solutions for unification must be proposed. Recently, several notable scholars have called for the field to unify around a collection of research questions (Rude, 2009; St.Amant & Meloncon, 2016). There are also ways that editors of our existing forums can align content.

One approach is to adopt structured abstracts across all forums. Structured abstracts summarize key findings reported in an article and the means used to collect those findings. TC and TPC employ this convention whereas TCQ and JBTC continue to use topic abstracts: short (100–150 word) descriptions that only identify themes addressed by an article. Structured abstracts apply to critical, qualitative, and quantitative research, and the self-contained organization advances research and promotes knowledge sharing. Generally, readers are more likely to recall information in structured abstracts than topic abstracts (Hartley, 2004). Specifically, technical communication abstracts do not always provide sufficient information, requiring authors to read the article in detail and impeding systematic reviews of literature (Carliner et al., 2011). Structured abstracts also promote enhanced communication between academia and industry. The organization makes our research findings more accessible to practitioners, offering the opportunity to not only consume more information but to retain and then apply this information to workplace situations.

Another way to align content across forums is to integrate an implications section in our research. Again, TC serves as a model with its “practitioner’s takeaway,” a 100–word bulleted list that summarizes the practical implications of the research. While not all content has to speak directly to practitioners—TCQ articles, for example, often speak to academics about education—all research should offer implications for advancing the field. Integrating this convention also allows researchers to consider their ideas from a different vantage. If we academics cannot articulate how our research implicates technical communication teaching and practice, perhaps we should consider the purpose of exploring certain topics and if a technical communication forum is, in fact, the best forum for that research. This perspective encourages researchers to more broadly consider the purpose of research and more narrowly consider how individual research projects contribute to the field’s body of knowledge (St.Amant & Meloncon, 2016, p. 8).

Beyond the written forums for research dissemination, conferences have long been reliable sources for learning about processes, techniques, theories, and research within the field. However, even those conferences that would most appeal to both academics and practitioners (STC and IEEE ProComm) have, due to various constraints and economic realities, been further fractured, with STC being a (mostly) practitioner conference and ProComm being a (mostly) academic conference.

Adopting this first call to action would create more alignment within technical communication. Unifying elements would increase knowledge consumption and likely increase article citations. The accessibility of standalone elements like the structured abstract are also more apt to be re-printed and discussed in blogs and other electronic forums as well as motivate expanded dissemination activities, such as participating in podcasts or as a guest blogger. This exposure should only benefit academics’ tenure and promotion cases. They would continue to publish in the same recognized forums, but a more accessible presentation of their ideas would better communicate their research to a variety of audiences. Finally, adopting unified structural elements would help prepare the next generation of technical communicators. Graduate students and tenure-system faculty could consume information more efficiently and, theoretically, produce more of their own research in response. Managers would have more accessible information to the field’s trends, and newly hired writers and content developers would have a strong body of knowledge to apply to their assignment responsibilities.

Identify new audiences

Technical communicators are trained to adapt to a variety of audiences for specialized purposes across multiple platforms. Results from our study suggest that our content forums have remained unchanged for almost 30 years. Therefore, our second call to action offers approaches for identifying new audiences.

Academics rely on existing forums for tenure and promotion purposes. Articles in professional magazines then accomplish little in achieving these academic pursuits. However, the currency and accessibility inherent to professional forums could greatly benefit faculty with the impact of their research as well as their national and international reputations. For example, academics should consider contributing a 2000-word Intercom article or a TECHWHIRL post that summarizes some of their previously published peer-reviewed studies. If we are, in fact, conducting applied research, these alternative forums only help disseminate our work to a broader audience. Kirk St.Amant, a full professor at Louisiana Tech University, routinely publishes articles in Intercom that pivot ideas that he theoretically discusses in scholarly forums (such as Getto & St.Amant, 2015; St.Amant, 2015; St.Amant & Rice, 2015).

In addition to modifying and better using current forums, we should create new forums for research dissemination. The concept of forum has evolved since Smith’s (2000b) definition, which was developed prior to the proliferation of Web 2.0, social media, and mobile communication. As an example, Kim Sydow Campbell, a full professor at the University of North Texas, developed ProsWrite.com, a blog where she offers opinions on technical communication as well as presents her original research and research of others. Campbell created ProsWrite because her previous research was disseminated only in journals: “I’m not ready to stop talking in those contexts,” she wrote, “but I am tired of their constraints. So why not talk with fewer (or at least different) constraints here? There are things I really want to SAY” (July 2015). Similarly, Lisa Meloncon, an associate professor at the University of Cincinnati, hosts tek-ritr.com, which also publishes opinions and research. In her opening post, Meloncon wrote that she could invest her time in a blog only after receiving promotion and tenure (2015, July 8). Both Campbell and Meloncon are senior faculty, and dedicating time to more untraditional forums may be an opportunity tenure-track faculty do not have. At the same time, we should not dismiss the value these types of forums might bring in aligning our content, particularly those forums that already attract practicing technical communicators. It is incumbent upon academics, specifically ones at the senior-level, to conduct research on the ways these forums bring value not just to individuals and practitioners but also to other scholars and academic institutions.

Finally, journal editors should seek alternative audiences for the content they publish. During her tenure as editor-in-chief of TPC, Jo Mackiewicz encouraged authors to create podcasts that were housed outside the publisher’s paywall. Along this line, editors and publishers could better inform their readership of at least the table of contents to allow readers to know what topics are being covered by the journals. For example, while STC is the publisher of both TC and Intercom, only one tweet and one Facebook post was made by the STC from April 2015 to April 2016 regarding either publication.

This second call to action encourages all parties of the publication process (authors, editors, and publishers) to recognize the value in expanding the audience of scholarly content beyond, typically, other academics, who have institutional access to research.

Engage practitioners in research

A growing number of academics acknowledge that we need to focus on how our own research can be applied. However, practitioners also need to engage more with the content being created. Carliner (1994) argued that research that answers compelling questions had a strong indirect value in preserving jobs, increasing salaries, and establishing the credibility of technical communication (p. 616). Lewis (2015) offered a myriad of intrinsic and extrinsic reasons why practitioners might publish and encouraged them that “successful publication can enhance a company’s brand by virtue of increasing the external visibility and the reputation of employees” (p. 5). Our final call to action outlines how to engage practitioners in research.

Our initial proposal is that practitioners should create more of the content published within our scholarly forums; however, their professional priorities and reward regarding this endeavor is not necessarily feasible. Journals editors should account for these constraints and create new ways for practitioners to participate. For example, invited practitioners could write a 1–2-page response to peer-reviewed pieces, particularly in volumes focused on relevant topics like content management systems or intercultural communication. These responses would frame research through the lens that academics may not have the grounding to provide.

The field must also acknowledge the influence that many technical communication practitioners have in new, untraditional forums, such as blogs, websites, and social media. In turn, these influential bloggers and Tweeters should uniformly notify their readership of the academy’s advancements. For example, Johnson (2016, February 23) summarized findings from a TC article on lightweight DITA in a blog post. Given the amount of publicity provided by the publisher, Johnson’s high-profile blog undoubtedly increased awareness of this article, if not the actual readership then at least the knowledge that academics were researching this topic. The academics publishing research with relevant implications to the field could be further highlighted by participating in a podcast or being recruited to guest blog.

Finally, though some technical communication practitioners may not have the time or interest in creating and promoting content, academics still need input on what research would be valuable. As Meloncon (2015, July 8) blogged,

we need more practitioners to reach out and connect with local programs or make it known on social media that you’re willing to do some things like guest lecture in a class, hold a one-hour workshop, help students network, offer to spend time just talking to faculty, etc. We definitely don’t want to overwork you, but I truly am tired of running across comments all over the Internet about how disconnected and behind the times academics are. I’m not saying that it may not be true in some cases. But what drives me batty are those folks who will complain and point fingers and never offer to share their time or expertise.

Therefore, practitioners should consider opening workplaces for primary research, including surveys, observational studies, interviews, or quasi-experiments. These types of opportunities require cooperation and time. With their tenure clock ticking, it is perhaps not surprising that many junior faculty turn to research that does not rely on the cooperation of an organization that can rescind this access at a late date (an occurrence that has happened more than once to these academic authors). Existing forums, such as the STC’s Body of Knowledge could provide a means for both practitioners and academics to align their interests in this area.

This last call to action encourages all technical communicators to enable practitioner perspectives to influence our content more. We have identified ways that practitioners could engage in the entire research process. Overall, these three calls to action require engagement from all types of technical communicators. Groups of interested parties (journal editors, bloggers, subsections of academics) must communicate, align, and devise concrete solutions to real problems. Results from the present study indicate some content alignment as well as professional and programmatic growth. What we are proposing should not impede these accomplishments; forum writers and editors should not have content dictated to them and these forums should not lose their current identity in this process.

It oftentimes appears that academics and practitioners are from different planets, rotating in their own orbits. Results from the present study imply that the primary topics and audiences within our forums have remained unchanged for almost 30 years. There is also evidence that technical communicators are publishing in outside forums and that noticeable amounts of scholars from other disciplines are influencing our content. Yet, we have the opportunity to influence this trajectory. Academics and practitioners should align along common research goals of advancing the field and training the next generation of technical communicators. When determining future actions, perhaps we should consider what the results of a follow-up study in another 30 years would offer about the content alignment in technical communication.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Saul Carliner for his work and feedback on earlier drafts.

References

Agboka, G. Y. (2013). Participatory localization: A social justice approach to navigating unenfranchised/disenfranchised cultural sites. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22, 28–49.

Beaudin-Hayes, C. (2008). Training for transit. Intercom, 55(8), 36.

Blakeslee, A. M. (2009). The technical communication research landscape. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 23, 129–173.

Blakeslee, A. M., Cole, C. M., & Conefrey, T. (1996). Evaluating qualitative inquiry in technical and scientific communication: Toward a practical and dialogic validity. Technical Communication Quarterly, 5, 125–149.

Boettger, R. K., Friess, E., & Carliner, S. (2014). Who says what to whom? Assessing the alignment of content and audience between scholarly and professional publications in technical communication (1996–2013). Paper presented at the Proceedings of the IEEE 2014 International Professional Communication Conference, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Boettger, R. K., & Lam, C. (2013). An overview of experimental and quasi-experimental research in technical communication (1992–2011). IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 56, 272–293.

Boettger, R. K., & Palmer, L. A. (2010). Quantitative content analysis: Its use in technical and professional communication. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 53, 346–357.

Bottitta, J., Idoura, A. P., & Pappas, L. (2003). Moving to single sourcing: Managing the effects of organizational changes. Technical Communication, 50, 355–370.

Brady, M. A., & Schreiber, J. (2013). Static to dynamic: Professional identity as inventory, invention, and performance in classrooms and workplaces. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22, 343–362.

Bridgeford, T., & St Amant, K. (2015). Academy–Industry relationships and partnerships: Perspectives for technical communicators. Amityville, NY: Baywood Publishing Company.

Campbell, K. S. (July 2015). About Pros Write. [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://proswrite.com/about/

Carliner, S. (1994). Guest editorial: A call to research. Technical Communication, 41, 615–619.

Carliner, S. (2012). The three approaches to professionalization in technical communication. Technical Communication, 59, 49–65.

Carliner, S., Coppola, N., Grady, H., & Hayhoe, G. F. (2011). What does the Transactions publish? What do Transactions’ readers want to read? IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 54, 341–359.

Carliner, S., Legassie, R., Belding, S., MacDonald, H., Ribeiro, O., Johnston, L., . . . Hehn, H. (2009). How research moves into practice: a preliminary study of what training professionals read, hear, and perceive. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology/La revue canadienne de l’apprentissage et de la technologie, 35(1).

Carliner, S., Qayyum, A., & Sanchez-Lozano, J. C. (2014). What measures of productivity and effectiveness do technical communication managers track and report? Technical Communication, 61, 147–172.

Coppola, N., & Carliner, S. (2011). Is our peer-reviewed literature sustainable? Paper presented at the Professional Communication Conference (IPCC), 2011 IEEE International.

Coppola, N. W. (1997). Rhetorical analysis of stakeholders in environmental communication: A model. Technical Communication Quarterly, 6, 9–24.

Crandell, T. L., Kleid, N. A., & Soderston, C. (1996). Empirical evaluation of concept mapping: A job performance aid for writer. Technical Communication, 43, 157–163.

Deadrick, D. L., & Gibson, P. A. (2007). An examination of the research–practice gap in HR: Comparing topics of interest to HR academics and HR professionals. Human Resource Management Review, 17(2), 131–139.

Demback, B. (2015). Agile best practices for technical writers. Intercom, 62(8), 7–10.

DuBay, W. H. (1996). What is professionalism? Intercom, 43(8), 2.

Frost, E. A. (2013). Transcultural risk communication on Dauphin Island: An analysis of ironically located responses to the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22, 50–66.

Getto, G., & St.Amant, K. (2015). Designing globally, working locally: Using personas to develop online communication products for international users. Communication Design Quarterly Review, 3(1), 24–46.

Goubil-Gambrell, P. (1998). Guest editor’s column. Technical Communication Quarterly, 7, 5–7.

Greenacre, M. (2007). Correspondence Analysis in Practice. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall.

Hagen, P. (1998). Teaching American business writing in Russia: Cross-cultures/cross-purposes. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 12, 109–126.

Hartley, J. (2004). Current findings from research on structured abstracts. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 92(3), 368.

Johnson, T. (2015, August 5). Why is there a divide between academics and practitioners in tech comm? [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://idratherbewriting.com/2015/08/05/acadmic-and-practitioner-divide/

Johnson, T. (2016, February 23). Lightweight DITA article in Technical Communication Journal. [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://idratherbewriting.com/2016/02/23/lightweight-dita-hdita-model/

Kimball, M. A. (2015). Special Issue Introduction Technical Communication: How A Few Great Companies Get It Done. Technical Communication, 62, 88–103.

Kovner, L. A. (1998). Becoming a Usenet user. Intercom, 45(4).

Krippendorff, K. (2012). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Kynell, T., & Tebeaux, E. (2009). The Association of Teachers of Technical Writing: The emergence of professional identity. Technical Communication Quarterly, 18, 107–141.

Lam, C. (2014). Where did we come from and where are we going? Examining authorship characteristics in technical communication research. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 57, 266–285.

Lauren, B. (2015). App Abroad and mundane encounters: Challenging how national cultural identity heuristics are used in information design. Technical Communication, 62, 258–270.

Lee, C. (2013). Teaching evidence-based writing using corporate blogs. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 56, 242–255.

Lewis, J. R. (2015). When perishing isn’t a problem: publication tips for practitioners. Journal of Usability Studies, 11(1), 1–6.

Lindgren, B. (1996). An introduction to writing CD-ROMs. Intercom, 43(5), 10–11.

Lowry, P. B., Humpherys, S. L., Malwitz, J., & Nix, J. (2007). A scientometric study of the perceived quality of business and technical communication journals. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 50, 352–378.

Lysenko, L. V. (2010). Researching research use: An online study of school practitioners across Canada. Concordia University.

McGowan, U., Seton, J., & Cargill, M. (1996). A collaborating colleague model for inducting international engineering students into the language and culture of a foreign research environment. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 39, 117–121.

McNely, B., Spinuzzi, C., & Teston, C. (2015). Contemporary Research Methodologies in Technical Communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 24, 1–13.

Meloncon, L. (2015, July 8). Intersections at the Ivory Tower. [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://tek-ritr.com/intersections-at-the-ivory-tower/

Menz, M. T. (1997). Clip art comes of age. Intercom, 44(4), 4–7.

Pinelli, T. E., & Barclay, R. O. (1992). Research in technical communication: Perspectives and thoughts on the process. Technical Communication, 39(4), 526–532.

Prentice, S. (2014). Thinking about delivering your documentation as an eBook? [Article]. Intercom, 61(4), 18–21.

Raymond, M. (2012). Once upom a time… Intercom, 59(6), 32

Ronning-Hall, K. (2012). How I followed the money to marketing while staying true to tech comm. Intercom, 63(1), 10–15.

Rude, C. D. (2009). Mapping the research questions in technical communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 23, 174–215.

Rynes, S. L., Colbert, A. E., & Brown, K. G. (2002). HR professionals’ beliefs about effective human resource practices: Correspondence between research and practice. Human Resource Management, 41(2), 149–174.

Scott, M. (1996). Technical communicators as managers in the informated workplace. Technical Communication, 43, 83–87.

Selber, S. A. (1998). The Wired Neighborhood [Book Review]. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 41, 82–83.

Smith, E. O. (2000a). Points of reference in technical communication scholarship. Technical Communication Quarterly, 9, 427–453.

Smith, E. O. (2000b). Strength in the technical communication journals and diversity in the serials cited. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 14, 131–184.

Smith, F. R. (1985). The importance of research in technical communication. Technical Communication, 32, 4–5.

Smith, F. R. (1992). The continuing importance of research in technical communication. Technical Communication, 39, 521–524.

St.Amant, K. (2015, April). Reconsidering social media for global contexts. Intercom, 16–18.

St.Amant, K., & Meloncon, L. (2016). Addressing the incommensurable a research-based perspective for considering issues of power and legitimacy in the field. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(3), 267–283. doi: 0047281616639476

St.Amant, K., & Rice, R. (2015). Online writing in global contexts: Rethinking the nature of connections and communication in the age of international online media. Computers and Composition, 38, v–x.

Trunzo, S., & De Vries, J. (2012). Analytics aren’t only for MBAs: Measuring information architecture value. Intercom, 59(1), 24–28.

Villegas, D. M. (2015, July 20). Oh, the Academian and the Practitioner should be friends…Engaging TechComm Professionals [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://techcommgeekmom.com/2015/07/20/oh-the-academian-and-the-practitioner-should-be-friends-engaging-techcomm-professionals/

Watt, J., & van den Burg, S. (1995). Research methods for communication science. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Welhausen, C. A. (2015). Power and authority in disease maps visualizing medical cartography through yellow fever mapping. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 29, 257–283.

About the Authors

Ryan Boettger is an associate professor of professional and technical communication at the University of North Texas. His research has appeared in a range of journals, including Technical Communication Quarterly, IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, Journal of Writing Research, Across the Disciplines, and Journal of the American Medical Writers Association. He teaches courses in technical editing, grant writing, and teaching methods. Professionally, he has worked as a technical editor and a grants and proposals manager. He can be reached at Ryan.Boettger@unt.edu.

Erin Friess is an associate professor in the Department of Technical Communication at the University of North Texas. Her research explores best practices of usability and user experience, technical communication discipline progression, and technical communication curriculum development. Her research has appeared in IEEE Transactions of Professional Communication, Technical Communication Quarterly, Journal of Business and Technical Communication, and Journal of Usability Studies. She currently serves on IEEE Professional Communication Society’s Advisory Committee. She can be reached at Erin.Friess@unt.edu.

Manuscript received 2 May 2016; revised 7 August 2016; accepted 10 August 2016.

I think another key issue is the general readability of journal articles. An article may have valuable insight for practitioners, but the information is usually not presented in a usable or accessible way.

Journal articles, including this one, are unnecessarily difficult to read, with overlong paragraphs and sentences, very stiff language, insufficient/inscrutable headings, and tables/figures that are not closely enough tied to their associated text.