Allen Berry

Abstract

Purpose: In the emerging world of social media, social media platforms have offered a number of marketing opportunities but also a number of potential problems. This has led to a number of social media foibles that can create a public relations nightmare for the affected companies. This article will explore the emerging phenomenon of the corporate Twitter apology and the rhetorical constructs that are required for an effective apology.

Method: Using the strategies of Ruth Page and John Kador, I have analyzed successful and unsuccessful Twitter apologies. The success of these apologies is determined by the public response from the tertiary audiences comprised of Twitter followers.

Results: This study determined that successful Twitter apologies use a combination of Kador’s strategies (Recognition, Responsibility, Remorse, Restitution, and Repetition), originally implemented for analog apologies, adapted for electronic communications to make a successful social media apology.

Conclusion: Surviving any serious social media foible depends upon issuing a successful apology and doing so on the social media platform where the original offense took place. Social media mistakes, though unique in their scope and potential to reach an ever-expanding tertiary audience, can be managed using the same strategies that apply to analog apologies.

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- The emergence of Twitter has opened many opportunities for businesses to raise their public profiles.

- An unfortunate by-product of social media platforms is the possibility for their misuse, resulting in a public relations disaster.

- There is an emerging rhetorical genre of Twitter apologies wherein a corporate authority must make amends for the company’s unfortunate tweet.

- The Twitter apology has the potential to either undo the damage of the initial tweet or repair the damage, and improve the company’s standing in the public view so long as the social media representative utilizes the strategies of Recognition, Responsibility, Remorse, Restitution, and Repetition.

The universal presence of social media has created a number of new and interesting rhetorical situations, in both the realm of social strata and in the corporate world. Customers no longer need send a strongly worded letter to the physical offices of an offending corporation and wait an indeterminate amount of time for a reply. In the high-speed environment of social media, customers can now voice their concerns immediately via the company’s Twitter feed.

Conversely, this new media has also become a forum for quick, concise communication between corporations and consumers. This instant access medium where messages can be transmitted instantly, often without regulation, has been beneficial to companies. Businesses’ Twitter presence, as innovators in touch with both consumers and cutting-edge technology, can boost a company’s image. However, Twitter has additionally spawned an unintended consequence as a public relations hazard. This is due to the size of the tertiary audience of social media, which consists of the audience members that the tweets were never intended for. The tertiary audience pitfall has become seemingly unavoidable in the expanding world of social media. As a result, a strategy has begun to emerge for managing the conflicts that inevitably come as a result of misusing social media. This article will explore the phenomenon of the social media apology and how to properly navigate the potential public image disaster that can come as a result of a controversial tweet. Utilizing established strategies for corporate apologies and a sampling of controversial Twitter incidents, I will address best practices for managing the fallout from social media incidents. Particular emphasis will be placed on John Kador’s “Five R’s” strategy for effective apologies; recognition, responsibility, remorse, restitution, and repetition; as applied to social media incidents.

Marwick and Boyd, in their 2011 study of social media behavior, suggest that Twitter differs from email in that email is directed to a specific audience. Twitter differs in that a tweet reaches a broad audience. The authors suggest that

[Twittter] users write different tweets to target different people (e.g. audiences). This approach acknowledges multiplicity, but rather than creating entirely separate, discrete audiences through a single account, conscious of potential overlap among their audiences. However, the difference between Twitter and email is that the latter is primarily a directed technology with people pushing content to the persons listed in the ‘To’ field, while tweets are made available for interested individuals to pull on demand. (p. 120)

They go on to suggest that the ideal reader, as imagined by most writers, still exists in the social media realm, and that Twitter users write their tweets with these readers in mind. This imagined audience of presumably like-minded individuals is a particularly perilous one for a corporation, considering the wide audience of Twitter followers (see the Digiorno Pizza incident).

Given the relatively personal nature of social media, a Twitter account can represent the personal views and opinions of the user, and this is typically the case for individual accounts utilized by a single user. In this respect, the Twitter user is the gatekeeper of the content that he or she views or interacts with. Most social media platforms offer controls over what information is shared with others. Filters and user controls allow the social media user to decide who can read and post to their social media accounts. This factors in to the performance aspect of social media, where the user’s image is presented in various degrees of authenticity to the world at large. In essence, the Twitter account represents the person who uses the account. Marwick and Boyd (2011) suggest that this creates a measure of tension that

usually errs on the side of concealing on Twitter, but even users who do not post anything scandalous must formulate tweets and choose discussion topics based on imagined audience judgment. This consciousness implies an ongoing frontstage performance that balances the desire to maintain positive impressions with the need to seem true or authentic to others. (p. 124)

They further discuss the fact that Twitter users self-censor in order to avoid conflict while simultaneously posting personal information in their tweets designed for a particular audience. They point out that users constantly change their presentations based on their audiences and that “context collapse problematizes the individual’s ability to shift between these selves and come off as authentic or fake” (Marwick & Boyd, 2011, p. 124). In the context of the corporate Twitter account, the problem of concealing and revealing is even more complex. There is no physical presence or personality associated with the corporate account; at the same time, the account must be maintained by a human being. The difficulty occurs when this maintainer’s personal interests and perspectives differ from the company’s. On occasion, human users will accidentally tweet something that is contrary to the company’s views or, in some cases, purposely tweet a personal perspective that goes against company standards.

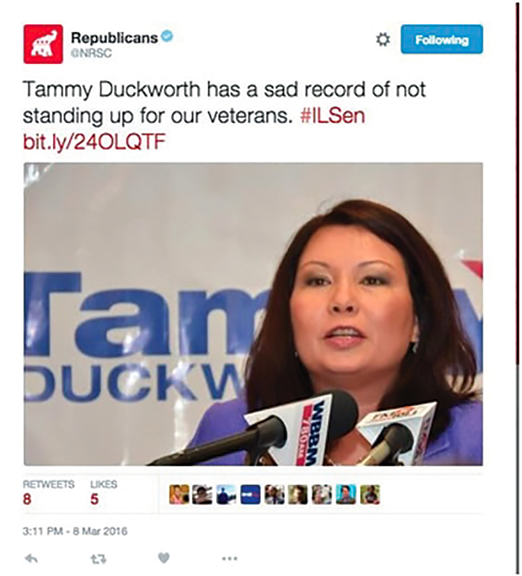

Consider the following disastrous examples of poor usage of social media. In 2016, the Twitter account of the National Republican Senate Committee (NRSC) issued a particularly unfortunate tweet regarding Senate Candidate Tammy Duckworth. The NRSC issued a tweet stating “Tammy Duckworth has a sad history of not standing up for our veterans. #ILSen bit.ly/24OLQTF” (Enterpreneur.com). What might appear on the surface to be the typical rhetoric of a contentious political season is grossly inappropriate in light of the fact that (now Senator) Duckworth lost both legs while serving in Iraq. Furthermore, she served as an assistant secretary for the Veteran’s Administration upon her return home.

Occasionally, the Twitter foible can be an ill-conceived marketing strategy, like the recent Twitter ad by the team at The International House of Pancakes (IHOP). IHOP’s Twitter feed is typically filled with visual humor and pop culture references presumably crafted to get quick laughs while advertising their products. A November 2015 Red Velvet Pancakes Photo tweet sported the caption “What is this? Velvet?” referring to a line from Eddie Murphy’s film “Coming to America.” The strategy is typically effective; however, it backfired in March of that same year. IHOP tweeted a pair of photographs of their pancakes with accompanying captions, using some decidedly insensitive slang referring to women. The first read “The butterface we all know and love.” The term “butter face” denotes a woman with a particularly appealing figure but a less appealing face. A second caption read, “flat but has a GREAT personality” (@IHOP). This caption is something of a double entendre, referring to the size of a woman’s breasts. These tweets quickly raised the ire of IHOP’s Twitter followers and others.

The case of Justine Sacco, former Public Relations Director of InterActiveCorp, the parent company of Match.com and LinkedIn.com among others, provides a strong cautionary tale on the reach and potential hazards of social media. Prior to departing on a trip to Africa, Sacco issued the following ill-conceived tweet: “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!” (as cited in Dimitrova, 2013, para. 2). Unknown to Sacco, who was in transit and without Internet access, the reaction to her post was immediate. According to an ABC News report, “A trending hashtag #HasJustineLandedYet and a parody account @LOLJustineSacco quickly appeared on Twitter. A fake Facebook account under her name was also created, where a post links to www.justinesacco.com, which brings up a donation page for Aid for Africa” (Dimitrova, 2013, para. 6). The company issued a statement distancing itself from Sacco, who was fired the day after her initial post. The offensive tweet was costly for Sacco but a potential public relations disaster for the companies that she represented. Another example of a Twitter disaster is that of the Chrysler employee who inadvertently tweeted from the corporate account, “I find it ironic that Detroit is known as the #motorcity and yet no one here knows how to fucking drive” (Altman, 2012). The Twittersphere, despite being an asset to corporate marketing and public relations, carries the constant risk of a potential disaster. The broader audience of social media is far reaching and practically immeasurable.

The expansion of social media allows for corporations to expand into new and previously unavailable markets, which creates the potential for reaching an audience numbering well into the hundreds of thousands. An example of the power of social media as a far-reaching communication platform is suggested by Ann Gentle, who describes utilizing Twitter to locate “a pair of Mario Jibbitz for Crocs shoes. I had two responses pointing me to sources for the item by the end of the day from different parts of the world” (Gentle, 2013, p. 255). The audience for tweets is both far-reaching and unpredictable, and, given the global scale of the software platform’s reach, Twitter’s pitfalls can potentially surpass its utility as a marketing tool.

Literature Review

Alice Marwick and Danah Boyd’s (2011) article “I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience” explains the difficulties associated with navigating the Twitter audience and its juxtaposition to the user’s identity. Their article is significant because of their work with context collapse, which, simply stated, is the infinite audience of a social media post. When a social media post is created, it can quickly expand beyond the original audience. This becomes even more complicated for corporations where the company’s public image on social media is essentially everything. A corporation relies on a human social media representative who has perspectives of his or her own that may differ from the corporation’s. This sometimes leads to problems when the representative offers his/her perspective instead of the company’s. Marwick and Boyd’s (2011) article is of crucial importance in understanding the roles of identity and context in social media communications.

David Bauman’s (2011) article on crisis management, “Ethical Approaches to Crisis Leadership,” offers a series of successful strategies for managing the damage caused—either intentionally or unintentionally—by a corporation. Bauman offers a leaner strategy than Kador’s (2009) for making amends for corporate wrongs, suggesting a three-step process: Acknowledge, Apologize, and Act. These ethical dimensions suggested by Bauman will offer further insight into the success or failure of Twitter apology strategies.

William Benoit’s (1997) discussion of corporate strategies suggests that a corporation’s wrongdoing is less important in the final analysis than the public’s perception of their wrongdoing. Benoit suggests that if there is a corporate scandal, the actual truth is less important than the way that the corporation reacts to it. Benoit’s list of corporate strategies will serve as a counterpoint to the work of Kador and a means of establishing an effective strategy for the Twitter apology.

Keith Hearit’s (2006) text about corporate responses to allegations of wrongdoing provides insight into the nature of a corporation’s persona and the public’s perception of it in times of a public relations crisis. He argues that a corporation’s public image becomes, for all practical purposes, an entity. Although corporations are not individuals, they come to be seen as such through their public actions and their public media. Given this phenomenon, where a corporation can be reduced to a defacto person, the company is then subject to the same scrutiny and disdain as an individual. This article explains how quickly a Twitter foible can become a publicity crisis.

Additionally, the work of Kim, Sung, and Kang discusses Twitter and, specifically, the phenomenon of retweeting, which they describe as “electronic word of mouth” (p. 19). This phenomenon is important because of the article’s focus on tertiary audiences. These audiences consist of readers for whom the original message was never intended, such as news media. This phenomenon is also explored through Web sources, such as Greg Beaubien’s Public Relations blog. He discusses how electronic sources, either republish and comment on particularly scandalous Twitter foibles, or discuss the fallout that comes as a result of them. Beaubien’s (2014) article talks about the structure of corporate apologies and how they express regret while stopping short of taking responsibility for the actual offense.

Although not limited to the electronic media aspect of the corporate apology, David Boyd’s (2011) model as illustrated by his article, “Art and Artifice in Public Apologies,” offers seven aspects of the public apology to Kador’s five. Furthermore, Boyd offers binaries for each of the aspects he examines, such as timeliness versus tardiness and empathy versus estrangement. This is particularly crucial when measuring the success of the apology.

Regarding the phenomenon of the Twitter apology, Ruth Page (2014), writing for the Journal of Pragmatics, denotes a set of criteria common in corporate Twitter apologies. These rhetorical criteria are determined from a broad sample size, derived from both private and corporate Twitter accounts. Page examines the frequency of occurrences of rhetorical devices peculiar to the apology.

According to Page (2014), an effective apology requires certain components. Chief among these is what she describes as the Illocutionary Force Indicating Device (IFID), which is the actual indication of apology. The IFID is “apology” or “sorry.” The components that follow are a means of ameliorating damage to the company’s reputation.

Explanations, Page (2014) points out, are less frequent in corporate apologies due to their potential to be either face saving or face damaging. Alternately, the company may attempt to evade responsibility by shifting blame to a third party who is associated with the company, as was the case with the unfortunate Home Depot tweet that featured two African American employees with a third employee in a gorilla costume. The photo was accompanied by the caption “Which of these drummers is not like the others?”

The evasion strategy is employed to mitigate any potential reputation damage that may come as a consequence of the explanation. Home Depot utilized the evasion strategy by tweeting that they had fired the agency who posted the offending tweet, thus shifting blame from themselves to their agency.

The offer of repair is a means by which the corporation may attempt to repair any potential damage by offering a remedy to the situation. Page (2014) points out that this strategy is applied at a 20% higher rate with corporations than their non-corporate Twitter counterparts. This component typically offers some tangible commodity as compensation for the offense; this can take on the form of a credit, a replacement of goods, or a refund.

Finally, Page (2014) suggests following up the initial apology by asking the offended party for more information. This accompanies the apology and is meant to restore the relationship with the customer. The structure of these information request tweets typically requires action on the part of one of the participants (either the customer or the company). They are intended to get the two parties communicating and repair the relationship between customer and company by expressing regret for the offense and reassuring the offended party that the offense will not happen again.

These apology criteria are similar in structure to those offered by John Kador (2009) in his book on effective apologies. While Kador’s book focuses on apologies rendered in the physical world as opposed to the cyber world, the rhetorical strategies are quite similar. Using Kador’s book as a lens for this study is due to his broader approach to the apology. Using Kador’s strategy as it applies to user experience makes his work an ideal lens to examine the corporate Twitter apology.

Kador (2009) lists five criteria for effective apologies: Recognition, Responsibility, Remorse, Restitution, and Repetition, which he refers to as “the Five Rs.” Recognition is, in principle, similar to Page’s (2014) IFID but is somewhat more complex in that it is the first element of the apology. Kador breaks down the apology strategy further into component parts of the illocutionary force indicating device. The recognition component dictates that the offending party acknowledges that harm has been caused. The move toward restitution cannot begin until this first crucial move has been made.

The responsibility component suggests that the offender acknowledges wrongdoing to the offended (and to the public depending on the size of the offense) that they have committed a wrong. This component of the apology begins the crucial business of repairing the damage done. Responsibility, according to Kador (2009), is a measure of integrity wherein the apologizer must admit sole culpability for the offense.

Remorse requires that the offender expresses regret for the offense and any damage that it has caused. This is similar in scope to Page’s (2014) IFID in that Kador (2009) suggests that without the actual phrase “I apologize” or “I’m sorry,” no effective apology can take place. He further states that there is no equivalent expression with which to communicate the apology. Remorse suggests regret for the offense and that the offender will not willingly repeat it.

The restitution component of the apology is the proactive effort on the part of the offender to repair the damage done by offering some means of compensation for the act. This is important in that it makes the relationship whole again, contains a sacrifice on the part of the offender, and communicates the importance of repairing the relationship to the offended party. Without the sincere offer of restitution, the relationship cannot be repaired.

Finally, repetition is the means by which the offender assures the offended that the initial harm will not be repeated. Kador (2009) suggests that the absence of this step causes otherwise appropriate apologies to lose their potency. With the repetition component of the apology, the relationship can move forward, because the fear and suspicion of being victimized again are alleviated.

Managing Consumer Conflicts Via Twitter

The ready availability of social media with its immediate and easy access allows for customers to air their grievances in a nearly immediate fashion, and, if the consumer has a large social media following, news of the offense can go viral in a matter of hours or perhaps even minutes. This complicates Kador’s (2009) 5 R’s strategy, which requires that the person making the apology determine to whom he or she should apologize. On the surface, the solution might seem obvious: apologize to the offended party. However, when applied to the far-reaching technology of social media, deciding to whom to apologize becomes a bit more difficult. After all, the scope of those who are offended by such a public foible is only limited to the number of people who have access to Twitter. In addition to the initial consumers, there is the secondary audience of consumers who read the offending tweet once it is retweeted by friends and by outlets that monitor social media trends.

Kietzmann, Hermkens, McCarthy, and Silvestre (2011), in their article on the ecology of social media, refer to theories of stable social interaction in both the physical and cyber worlds. They hypothesize that social media has altered the old model by expanding the potential number of possible relationships that users can maintain. According to them:

A widely discussed group relationship metric is Dunbar’s Number, proposed by anthropologist Robin Dunbar (1992), who theorized that people have a cognitive limit which restricts the number of stable social relationships they can have with other people to about 150. Social media platforms have recognized that many communities grow well beyond this number, and offer tools that allow users to manage membership. (p. 243)

The rise of Twitter and other social media has made it possible for users to expand their group of friends beyond their local community. A once relatively manageable body of friends with common interests becomes a multitude of individuals with various levels of interaction and emotional proximity to the social media user. The Original Poster (OP) may, and likely does, have numerous followers he or she has never met or interacted with outside of social media. Twitter users, be they corporate or private, may have followers numbering in the hundreds or even thousands. These followers’ tangential relationship to the user is typically unreciprocated, and yet they enjoy some measure of emotional attachment to the Twitter users they follow. These mostly anonymous individuals are known only by a screen name to the Twitter users they follow—if they are recognized at all. These followers compose the largest and most difficult to navigate audience of the social media world: the tertiary audience.

The Infinite Tertiary Audience of Twitter

In the realm of social media, there are only the primary and tertiary audiences. Ordinarily, in corporate communication, the message is passed through a series of secondary readers, or gatekeepers, who approve and control the content of the message prior to its distribution. The additional filters provided by gatekeepers (who are oftentimes the social media reps themselves) and secondary readers are either greatly reduced or completely removed due to the near instantaneous nature of social media. Whoever is in charge of the social media account is in direct contact with the audience; the message is filtered only by the Twitter user’s discretion. This can lead to trouble when an unfiltered message is sent that damages the company’s reputation, and, given the phenomenon of retweeting, the tertiary audience of an ill-conceived tweet is practically infinite.

Robert McEachern, in his 2013 article “Social Media Challenges for Professional Writers,” addresses one aspect of this tertiary audience as “watchdog groups.” Like all tertiary audiences, these are people to whom the message is not initially intended but who wield some manner of socio-political power. Typically, the watchdog audience is a small group of people; however, McEachern points out that “with social media writing, nearly everyone with an Internet connection is a potential watchdog audience: texts can easily be sent, reposted, retweeted, or otherwise made available to readers who were not part of the original, focused audience” (p. 281). McEachern offers as proof the example of an incident that occurred following the unfortunate response by an American Cancer Society (ACS) website blogger to a Facebook group calling for a bald Barbie for children with cancer. The blogger stated that, given the relatively rare occurrence of cancer in children, the money potential customers might spend on the doll would be better spent in the form of donations to the ACS. Despite the efforts of the blogger to make amends, removing the offending post and replacing it with an apology, other bloggers re-posted the original entry. As a result, the ACS’s Facebook page was inundated with negative comments from family members and supporters of children with cancer. In his analysis of the incident and its aftermath, McEachern states,

Readers of the ACS blog made other interested parties aware of the ACS blog entry, who made still others aware; eventually, these readers collectively had enough power to influence both the ACS and Mattel. Writing in social media has changed the extent of watchdog audiences exponentially, as more outlets allow for easier exchange. (p. 284)

Naturally, the professional writer and the corporate media specialist must consider the possible implications of the broader audience and its reaction to what the writer posts. However, as demonstrated by the watchdog group phenomenon, the need for caution is far greater in a world where social media is so prevalent in everyday life.

Does The Apology Make A Difference?

According to Keith Hearit, “For corporations, their social personae is their currency their stock in trade. Damage to their carefully constructed personae concievably will have an effect on thier bottom lines. . . . With public criticism, a previously unadulterated persona has become soiled and the organization’s persona has become the issue” (2006, p. 11). In essence, the public image of the company becomes indistinguishable from the company in the minds of the public. Hearit states that “Although the personae are synthetic creations, in effect, they become ‘a real fiction’ (Fisher, 1970, p. 132) because they develop into the vehicle by which individuals experience an organization” (p. 11). This is perhaps most true in the case of corporate Twitter accounts, which users come to view the same as private Twitter users rather than faceless entities. The corporate persona is magnified through the Twitter account, which requires human effort to operate. While social media grants the company a measure of humanity, it also creates the illusion that the corporation itself is a person capable of causing personal offense and harm. This being the case, it is vital that the company act as a person when it has caused harm or offense.

For corporate entities, making an apology can be a particularly risky proposition. There is the common belief that offering an apology carries with it the potential for legal culpability. However, an article by Janet Tovey (2003) in Technical Communication states that “A review of formal (‘black letter’) and common law indicates that apologies generally do not constitute evidence of guilt and that, in fact, they sometimes have positive consequences for the apologist” (p. 420). A proper apology can have the desired restorative effect desired by both the company and the offended party. However, issuing an apology is no guarantee of forgiveness. Restoring trust is especially complicated in the relatively new dimension of social media.

An insensitive or poorly worded tweet can result in a public relations disaster for a corporation; whether or not an apology on the part of the social media representative or the company makes a difference is a matter of some question. Kador (2009) suggests that an effective apology requires the offender to admit wrongdoing, which is at best uncomfortable. An inelegantly crafted response can be just as damaging, if not more so, than the offending tweet.

The importance of taking responsibility is perhaps best demonstrated by Esquire magazine’s foible of a few years ago. On September 11, 2013, Esquire magazine posted the now famous photograph of “the falling man” from September 11, 2001, in the style section of its website. The text accompanying the photograph boasted the following heading: “Making Your Morning Commute More Stylish, How to Look Good on your Way to Work.” Once the error was caught, the magazine’s media rep took to Twitter with the following dismissive response: “Relax everybody. There was a stupid technical glitch on our ‘Falling Man’ story and it was fixed asap. We’re sorry for the confusion” (@esquire). The apology offered by Esquire does contain the requisite IFID and additionally offers an explanation of the cause for the offense. There is arguably the vague offer of forbearance, but it lacks the element of responsibility. Instead, the Esquire apology attempts to deflect the blame from itself by shifting blame to a secondary non-entity: technology. In essence, Esquire suggests that there is no one at fault in this blunder and that it is simply a case of bad luck. The most egregious failure of Esquire’s apology is its condescending tone. Not only does the apology refuse to accept responsibility, in its attempt to downplay the offense, it also condescends to its intended audience and, by doing so, denies any responsibility for the error in the first place. Although it may be impractical, even impossible to engage all aspects of Kador’s (2009) and Page’s (2014) strategies, some of the key features must be utilized to be rhetorically successful.

Tertiary audiences can be very unforgiving of social media blunders, particularly if the apology is poorly handled. In the age of social media, there are no longer small public relations mistakes. Depending on the number of the account’s Twitter followers, a Twitter foible has the potential audience of thousands, and such mistakes are virtually impossible to cover up or erase.

The website Twitlonger, created by Web developer Stuart Gibson, allows users to post messages that can be linked to Twitter and expand beyond the diminutive 140 characters it allows. ESPN Sportscaster Stephen Smith took to Twitlonger to apologize for comments he made about domestic violence in light of the Ray Rice controversy. A portion of the Smith’s text reads:

My series of tweets a short time ago is not an adequate way to capture my thoughts so I am using a single tweet via Twitlonger to more appropriately and effectively clarify my remarks from earlier today about the Ray Rice situation. I completely recognize the sensitivity of the issues and the confusion and disgust that my comments caused. (@stephenasmith)

These incidents, among others, suggest that a large enough social media blunder requires a much larger rhetorical response, wherein one social media’s text is addressed on another platform. Responding to a Twitter failure on another platform; such as Facebook, Blogger, or a company website; does allow for greater space to address the criteria set forth by Kador’s (2009) and Page’s (2014) writings on effective apologies. However, responding via a different medium means that those who were initially offended may be alienated from the resulting apology. However, an elegantly rendered series of tweets can be equally effective, if not more so than cross-media reparation. Marketing Consultant Tami Wessley of the Weidert Group marketing agency suggests responding first on the platform where the incident first took place. Wessley states,

If the flare-up happened on Facebook, respond there first—it won’t help to jump platforms if the conversation and chaos are happening within another audience. After that initial response, go ahead and expand to other outlets if you believe the situation will “spread,” develop a dedicated microsite to house your official response and messages if the situation warrants, and direct anyone interested to that site. (2016, para. 6)

Wessley’s strategy suggests that the best platform for addressing a social media crisis is the platform where the trouble initially occurred. Logically speaking, both primary and tertiary audiences will be drawn to the site of the original post and therefore more likely to read any attempts at apologizing the offender might make. This strategy is two-fold in that it may serve to reduce the damage by assuaging those who took offense and prevent the tweet from (to use a bit of Internet slang) “flaming.” Second, the aforementioned audiences will likely return to the site of the conflict rather than seek information or redress on the company’s other media, such as the corporate website.

Additionally, attempting to apologize across other platforms places the offended party, who is already under duress, in a position where they are responsible for taking action to resolve the offense. According to Ruth Page (2014),

The directives and requests that require the customer to initiate further interaction are inherently face-threatening, for they place the obligation to pursue reparation with the customer, not with the company. This is a risky strategy, for there is no guarantee that the customer will continue the interactions, and further good will (and future customers) may be lost. (p. 40)

Though Page’s analysis applies to the practice of requesting the customer call for a face-to-face interaction, the principle remains the same. Even tweeting a link to an apology on a separate social media platform or company blog requires further action on the part of the offended parties and carries the same risk of additional damage. The most effective apology restricts making reparations to the platform in which the initial offense occurred. An offensive tweet should be apologized for on Twitter, an offensive Facebook post on Facebook, and so on.

Methods

For the purposes of this study, in September of 2014, I compiled a convenience sample of forty corporate Twitter apologies by entering the terms “Twitter Apology” into Google. These tweets were analyzed on the basis of the five dimensions of effective apologies set forth in John Kador’s (2009) book, Effective Apology: Mending Fences, Building Bridges, and Restoring Trust. The success of the apologies was rated on the basis of public response via Twitter users. Kador’s formula succinctly defines the aspects of an effective apology. Kador’s study uses examples from the political world similar to John Edwards’ now famous 2008 apology. Conversely, it uses business world examples, like Turner Broadcasting’s apology for their ill-conceived flashing Aqua Teen Hunger Force guerilla marketing campaign. Using Kador’s “Five R’s,” as a basis, I examine the tweets’ rhetorical construction as well as their social implications. The verbal and rhetorical structure of the individual tweets will be analyzed in terms of the frequency of individual dimensions’ occurrence across the sampling of apologetic tweets. Additionally, this article will examine the audience and medium that the individual apologies must address.

Kador’s Strategy in Application

Engaging all five of Kador’s (2009) strategies is, in most cases, impossible, but some combination of these strategies is necessary to achieve a successful apology. Of the sampling of 40 Twitter apologies, all acceptable apologies demonstrated at least some portion of the five criteria. The following graphic demonstrates the percentages of each of Kador’s dimensions in relation to the 40 Twitter apologies surveyed:

Table 1. Kador’s Strategy applied to tweet sample

| Kador’s Five Criteria in Relation to Successful Twitter Apologies | |

|---|---|

| Recognition | 97.5 % |

| Responsibility | 57.5 % |

| Remorse | 92.5% |

| Restitution | 37.5 % |

| Repetition | 17.5 % |

Recognition

Recognition is the aspect of the apology wherein the offender acknowledges that he or she has hurt someone. In the recognition phase, the offender establishes what he or she is apologizing for, how it affected others, to whom to apologize, and what form the apology should take. Once the offender has established that he/she has done something wrong and that an apology should be issued, only then can the work of the apology begin.

In the sampling of 40 Twitter apologies examined in this paper, 97.5% of the tweets examined acknowledged the offense within the body of the text. For example, one of the more effective Twitter apologies was posted by Julianne Hough apologizing for a controversial Halloween costume: “I am a huge fan of the show Orange is the New Black, actress Uzo Aduba, and the character she has created. It certainly was never my intention to be disrespectful or demeaning to anyone in any way. I realize my costume hurt and offended people and I truly apologize” (@juliannehough). Not only does Hough acknowledge the offense but also takes the extra step of explaining that she understands how her actions hurt others, thereby acknowledging the effect her actions had on others.

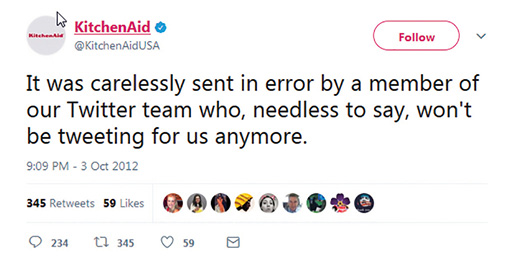

Additionally, a media rep for KitchenAid engaged the recognition strategy in the company’s response to a famously insensitive tweet about the death of President Barack Obama’s grandmother. After initially blaming the company’s social media rep and assuring followers that the rep had been fired, a spokesman for the company stated, “I would like to personally apologize to President @BarackObama, his family and everyone on Twitter for the offensive Tweet sent earlier” (KitchenAid, 2012). This succinct but effective reply acknowledges that an offense was committed and further acknowledged who the offended parties were. Although the limitations of the platform do not allow for a lengthy mea culpa, the KitchenAid response fulfills the requirements of recognition by addressing the parties directly and acknowledging that the initial tweet was hurtful.

Responsibility

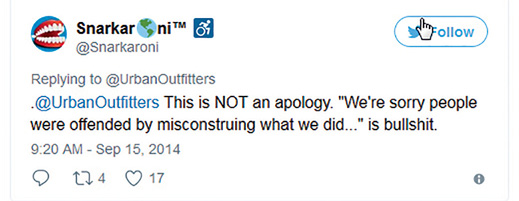

There is often an attempt on the part of the party making the apology to avoid culpability for the offense, instead casting it in the light of unfortunate circumstance. This is best demonstrated by the shopworn cliché, “mistakes were made,” wherein no one accepts responsibility. However, Kador (2009) states in his criteria for effective apologies, “In the responsibility dimension there is a focus on making the apology more about the needs of the victim than about redemption for the offender” (p. 73). The offending party must acknowledge fault for their actions and, in doing so, take full blame for the harm that they have caused. From the samples selected for this paper, only 57.5 % expressed responsibility for the offense in question. There are a number of possible reasons for this reduced number, one of which is the need to save face as suggested by Page’s (2014) findings. Referring to an earlier theorist’s work on apology strategies, she suggests, “Benoit’s strategies for corrective action may include a promise of forbearance, or make an offer of repair to compensate the victim. In contrast, if the apologiser wishes to downplay their role in the perceived offence, they may include explanations which variously deny the offence or evade responsibility” (p. 32). This is evident in the apology by Urban Outfitters for their Kent State sweatshirt, “Urban Outfitters sincerely apologizes for any offense our Vintage Kent State Sweatshirt may have caused. It was never our intention to allude to the tragic events that took place at Kent State in 1970 and we are extremely saddened that this item was perceived as such” (@UrbanOutfitters). Urban Outfitters’ apology avoids taking any responsibility for the offense, instead redirecting blame onto those who took offense at the product. This is standard fare according to Benoit’s theory. Rather than express mortification directly, Urban Outfitters chose to attempt the “Reducing Offensiveness of Event” strategy, employing a combination of the sub-strategies of minimization and attacking the accuser. This strategy could be employed to great effect in the case of a single known accuser, or a small party of accusers. However, the relative anonymity afforded by Twitter makes such strategies, at best, risky. A small group of accusers might be easily contained, even discredited in a real-world incident, but the size of a Twitter audience is unquantifiable and therefore it is impossible to discredit the entire audience.

By refusing to accept fault for their actions, the company garnered the ire of their followers, who retorted via Twitter:

Twitter followers responded quickly, stating that they would no longer be patronizing Urban Outfitters again because of this incident.

By failing to accept responsibility, the company exacerbated an already unfortunate public relations failure. Contrast this incident with the DiGiorno Pizza incident. A DiGiorno’s pizza social media rep responded to a trending topic: hashtag #WhyIStayed. The topic began in the wake of the recent Ray Rice abuse scandal, with women tweeting about their personal experiences with abuse. The social media representative, in an effort to raise brand awareness by weighing in on a trending topic, posted the following tweet: “#WhyIStayed. You had Pizza.” (@DiGiorno Pizza). The representative quickly apologized for the offending tweet and followed up with an explanation: “A million apologies. I did not read what hashtag was about before posting” (@DiGiornoPizza). However, this was not the end of DiGiorno’s restitution. The DiGiorno representative also engaged both recognition and responsibility for the offense and repeatedly expressed remorse for his actions and, by implication, ensured that such an incident would not occur again, satisfying Kador’s (2009) requirement for repetition.

DiGiorno’s mistake was a potentially damaging social media foible, given the currency and scope of both the mistake and the societal issues that surround it. The social media rep took full responsibility and made the effort to personally respond to all social media users who tweeted in response. A sampling of those responses offers an excellent case study in best Twitter apology practices:

In the case of the DiGiorno Twitter debacle, the company’s social media representative addressed each response individually. Additionally, the media rep utilized the tools of an effective apology and made no effort to excuse the blunder. Two days after the initial mistake, after a number of responses to the tertiary audience, the company rep posted a final, blanket apology to the company’s feed, stating: “We heard from many of you and we know we disappointed you. We understand, and we apologize to everyone for this mistake” (@DiGiornoPizza). The DiGiorno incident represents best practices in responding to a social media blunder by addressing not only the tertiary audience but also each responding audience member individually. The media rep acknowledges that an offense has been committed and also apologizes personally; in doing so, DiGiorno acknowledges the importance of the most unpredictable demographic, the tertiary audience. However, the potency of this apology does not lie exclusively in the fact that the rep addresses each respondent. The media rep also offers an apology to anyone who might have been offended by DiGiorno’s tweet and said nothing. DiGiorno’s approach is superior because it recognizes the personal nature of the offense and seeks to address it personally with the injured parties.

The response to DiGiorno’s apology was quite favorable, prompting one follower to reply: “People need to learn to come clean gracefully like @DiGiornopizza. You’re forgiven, pizza man” (@carlydermott). Utilizing the media where the offense took place allowed for DiGiorno to exercise control over the response, and the audience to whom they would respond. Changing the venue for responding to the offense would be to risk losing the initial tertiary audience and possibly even expanding the audience by raising awareness of the offense. By staying on Twitter, the company wisely navigated the perceived intimacy that Twitter followers enjoy with the users they follow. In short, the DiGiorno social media rep utilized the company’s persona to respond to its followers as if the account were representative of an individual as opposed to a corporation.

The company did not attempt to dissemble or divert blame from itself. Instead, they acknowledged full responsibility for their offensive tweet and made every effort to address each complaint directly.

Remorse

Perhaps one of Kador’s (2009) most important criteria is the admission of remorse. He states that “Because there is no way to know whether someone else is experiencing remorse, we rely on a variety of verbal and nonverbal cues. By far the most important verbal cue, without which a statement falls short of being an actual apology, is the phrase ‘I’m sorry’ or ‘I apologize’” (p. 85). Given that body language and other non-verbal cues are absent in electronic communication, it is a bit more difficult to express remorse. Unlike a face-to-face apology, on social media, the non-verbal dimensions of body language, tone, and facial expression are unavailable.

In the sampling of Twitter apologies drawn for this study, 92.5% expressed remorse via Illocutionary Force Indicating Device. Of the apologies studied, the word “sorry” appeared ten times, whereas variations on “apology/apologize” appeared 33 times (some apologies from the sample utilize multiple IFIDs). Of the apologies that lacked any IFID, the corporate tweets were an attempt to minimize the offense or to defer blame for the initial offense. Case in point, the Kenneth Cole apology for attempting to co-opt the Arab Spring as a marketing tool, “Kenneth Cole: ‘Re Egypt Tweet: we weren’t intending to make light of a serious situation. We understand the sensitivity of this historic moment -KC’” (Ehrlich, 2011). While the tweet does respond to the initial offense, it lacks the expression of remorse and seeks only to minimize culpability for any outrage that it may have caused. In similar fashion, the Gap attempted to remove all blame by suggesting that their mistake was a misunderstanding on the part of their followers. The Gap tweeted, “To all impacted by #Sandy, stay safe. Our check-in and tweet earlier were only meant to remind all to keep safe and indoors” (Wasserman, 2012). The apology here does not meet the criteria for an apology at all, due to its lack of any of Kador’s criteria. Instead, it seeks to divert any attention away from the insensitive nature of the tweet or to even admit any wrongdoing. Twitter can be used as an effective media to apologize for mistakes, as was demonstrated admirably by DiGiorno Pizza. The representative responded to every tweet and the responses were all posted on the media platform where the original offense was committed.

Restitution

Restitution is an aspect of Kador’s (2009) strategy that presents certain challenges in the Twittersphere. Making restitution in the physical world can be completed in a number of ways. The offender might offer coupons, which was the strategy employed by the manager of a St. Louis Chipotle restaurant for a disgruntled customer who happened to write for the Riverfront Times. The customer took to Twitter to lodge her complaint and was quickly contacted by Chris Arnold, the company’s social media rep. This resulted in the manager apologizing to the customer and offering coupons. The social media rep followed up as well: “Manager did the right thing. May be the only right thing on this visit. My apologies. Hope you’ll use the coupons to see us again” (Wheeler, 2012). However, restitution is not necessarily restricted to the exchange of tangible goods or services. Kador states that “restitution is the clearest expression of the offender’s desire to restore the relationship” (p. 97). This can be done by offering the acknowledgment that work is being done to repair the relationship and that can be accomplished by stating that some sacrifice has been made to that end. Consider the previously mentioned Home Depot controversy where a social media rep tweeted a racist photograph. In this instance, restitution took the form of firing the rep who made the racist tweet. The apology contained the promise that someone was held accountable for the injury he had committed. Although there was no tangible offer of goods or services, there was action taken to call the party responsible into account for his actions.

Repetition

The final dimension of Kador’s strategy for apologies is repetition. In order for an apology to be effective, there must be the assurance that it will not happen again, and in the realm of Twitter apologies, it is the rarest. As proven by our sample, only 17.5% of the apologies sampled offered assurance that the offense would not be repeated. According to Kador (2009), “This is the step that many otherwise thoughtful apologies omit. But through that omission otherwise good apologies suffer, because all victims may have a conscious or unconscious barrier to accepting an apology” (p. 113). Accepting an apology makes the wronged party vulnerable by extending trust to someone who has already violated said trust. Acceptance places the offended party at risk of being hurt again. An assurance from the offender that the harm will not reoccur helps restore the broken trust.

Case in point is the message issued from KitchenAid’s Twitter account, which made a joke about President Obama’s grandmother’s death prior to his taking office. The tasteless joke was quickly removed from the company’s account and an apology issued. The following apology appeared on the company’s Twitter feed:

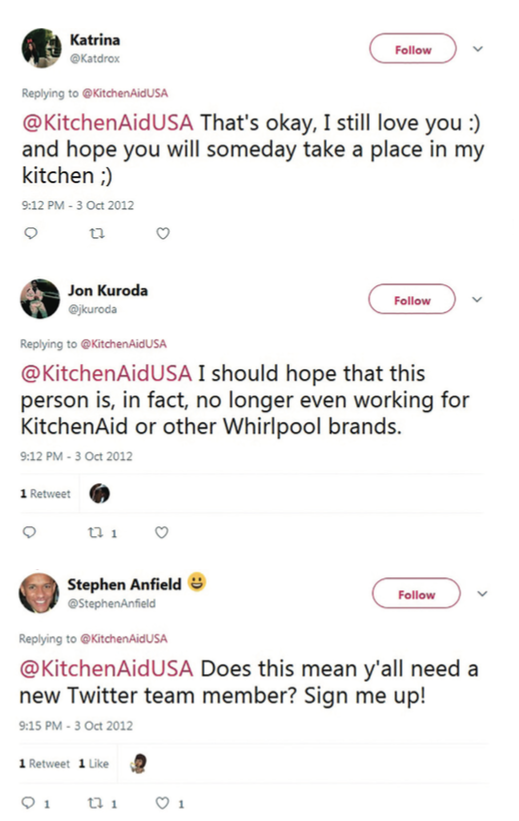

This tweet was followed shortly by a second tweet from the company offering the assurance that repetition would not occur.

By assuring followers that the person responsible for the offense would no longer be in a position to repeat it, KitchenAid was able to restore the relationship with their customers as evidenced by Twitter follower’s responses. Although there were those who were not so ready to forgive, the reaction was mostly positive.

An effective apology should contain the dimension of repetition. In order to restore trust, there must be the assurance that the offense will not be repeated and damage the mended trust. This is difficult for both parties in the Twittersphere, because the audience and its sensibilities are, at best, unpredictable. Depending on the nature of the offense, the assurance of repetition is not always possible; however, as evidenced by the KitchenAid example, when possible, the attempt should be made.

Conclusion

Social media is a difficult landscape for corporations to navigate. Despite its obvious benefits with regard to inexpensive (and in some cases cost-free) marketing and promotion, social media does carry a measure of risk. The instantaneous nature of Twitter communication makes mistakes difficult to recover from. The emerging genre of the Twitter apology is still developing, but the strategies laid out by John Kador (2009) provide an effective approach to making amends for offenses. In addition to the dimensions he suggests, it is crucial that the party offering the apology consider and address both primary and tertiary audiences. Thanks to the inception of social media, an offense that might have once been handled quietly among a few involved parties now has the potential to destroy a company’s public image. The modern audience is only limited to those who have access to the Internet. A small measure of private restitution is no longer sufficient to make reparations. Modern social media audiences have become de facto stakeholders in the interests of the brands they follow. Therefore, social media users expect a public mea culpa in the event of public debacles. Addressing these offended parties is crucial and it must be done in the medium where the offending remarks were posted. To do otherwise is to risk alienating or failing to reach the primary and tertiary audiences of the original offense. Done correctly, the Twitter apology can restore consumer confidence and strengthen the brand’s image. Therefore, it is crucial that both corporate social media representatives and small business users educate themselves on the proper strategy for managing social media blunders.

In order to create a successful Twitter apology, the social media manager must employ some of the aspects of traditional apologies but with a mind toward the ever-expanding nature of the Twitter audience. First and foremost, the apology must be managed on the platform where the initial offense took place. Moving the discussion beyond Twitter, to the company website or Facebook account, is to risk alienating the original audience who might be following the fall-out of the initial response. Additionally, apologizing on a different platform can expand the audience by drawing attention to the inciting event.

Acceptance of responsibility is of key importance. Contrary to the standard rule of avoiding culpability or attempting to shift blame to a third party, social media blunders are so clearly public there is little point in attempting to deny the offense. Once the initial offense has occurred, make the apology quickly in order to try to control the potential damage. Remember that a particularly damaging tweet can go viral, so the audience expands extremely quickly. Context collapse is an important consideration when dealing with Twitter foibles. Consistently, the verbal and non-verbal cues that provide context and clarity are removed, leaving the information to the interpretation of the reader—an interpretation that can take on unintended dimensions. Because the offense takes place on Twitter, the audience is potentially global, and the stakeholders become anyone who has access to social media and whose impression of the company might be negatively affected.

As a matter of course, the social media manager should, if at all possible, respond to everyone who replies. This was best demonstrated in the case of DiGiorno’s Pizza, where the social media rep followed up with a blanket tweet apologizing to any potential audience members who witnessed the offense and chose not to respond. Although no strategy is guaranteed to reach all audiences, this strategy will address the greatest number of potential audiences.

As demonstrated by the examples of Urban Outfitters and AT&T, an apology that fails to accept responsibility for the offense or attempts to shift blame only further angers the audience and increases the damage to the company’s public image. While even the sincerest apology will have its detractors, an insincere post is subject to the same viral consequences as the initial offense.

The corporate Twitter apology differs in scope and structure from the standard corporate apology principally in the way that it must address its audience. A Twitter offense is much more difficult to address due to the speed and near infinite reach of the platform. In dealing with a social media foible, speed and comprehensiveness are invaluable. Although these incidents can be damaging to a corporation’s image, by employing this effective strategy, a company can recover and emerge with a stronger public image.

References

Alter, C. (2013, November 7). Home Depot apologizes for racist tweet. Time, Inc. Retrieved from http://business.time.com/2013/11/07/home-depot-apologizes-for-racist-tweet/

Altman, J. D. (2012, February 22). The most disastrous corporate tweets that probably got people fired. Someecards, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.someecards.com/news/so-that-happened/the-most-disastrous-tweets-that-probably-got-people-fired/

@DiGiornosPizza. (2014, September 8). A million apologies. Did not read what the hashtag was about before posting [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/digiornopizza/status/509178151927173120?lang=en

@DiGiornoPizza, (2014, September 9). We heard from many of you, and we know we disappointed you. We understand, and we apologize to everyone for this mistake [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/digiornopizza/status/509472611802173441

@esquire (2013, September 13). Relax, everybody. There was a stupid technical glitch on our “Falling Man” story and it was fixed asap. We’re sorry for the confusion [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/esquire/status/377826870865448960

@juliannehough. (2013, October 26). I am a huge fan of the show Orange is the New black, actress Uzo Aduba and the character she has created. It certainly was never my intention to be disrespectful or demeaning to anyone in any way. I realize my costume hurt and offended people and I truly apologize [Tweet]. Retrieved from http://www.twitlonger.com/show/n_1rqfec1

@stephenasmith. (2014, July 25). My series of tweets a short time ago is not an adequate way to capture my thoughts so I am using a single tweet via Twitlonger to more appropriately and effectively clarify my remarks from earlier today about the Ray Rice situation. I completely recognize the sensitivity of the issues and the confusion and disgust that my comments caused. First off, as I said earlier and I want to reiterate strongly, it is never OK to put your hands on a women. Ever. I understand why that important point was lost in my other comments, which did not come out as I intended. I want to state very clearly. I do NOT believe a woman provokes the horrible domestic abuses that are sadly such a major problem in our society. I wasn’t trying to say that or even imply it when I was discussing my own personal upbringing and the important role the women in my family have played in my life. I understand why my comments could be taken another way. I should have done a better job articulating my thoughts and I sincerely apologize [Tweet]. Retrieved from http://www.twitlonger.com/show/n_1s2kd5m.

@UrbanOutfitters. (2014, September 15). Urban Outfitters sincerely apologizes for any offense our Vintage Kent State Sweatshirt may have caused. It was never our intention to allude to the tragic events that took place at Kent State in 1970 and we are extremely saddened that this item was perceived as such. The one-of-a-kind item was purchased as part of our sun-faded vintage collection. There is no blood on this shirt nor has this item been altered in any way. The red stains are discoloration from the original shade of the shirt and the holes are from natural wear and fray. Again, we deeply regret that this item was perceived negatively and we have removed it immediately from our website to avoid further upset [Tweet]. Retrieved from http://www.twitlonger.com/show/n_1sagorq

Bauman, D. (2011). Evaluating ethical approaches to crisis leadership: Insights from unintentional harm research. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(2), 281–295. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0549-3.

Beaubien, G. (2014, February 6). Are corporate Twitter apologies a result of tweeting too often? PRSA. Public Relations Society of America. Retrieved from https://www.prsa.org/SearchResults/view/10538/105/Are_Corporate_Twitter_Apologies_a_Result_of_Tweeti#.WFBiR31ywso

Benoit, W. L. (1997). Image repair discourse and crisis communication. Public Relations Review, 23, 177–186. doi:10.1016/S0363-8111(97)90023-0

Boyd, D. P. (2011). Art and artifice in public apologies. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(3), 299–309.

Bowdon, M. A. (2014). Tweeting an ethos: Emergency messaging, social media, and teaching technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 23, 35–54. doi:10.1080/10572252.2014.850853

Collins, B. (2014). Abuse magnets: The people behind corporate Twitter accounts. PC Pro, (239), 34

Chu, S., & Sung, Y. (2015). Using a consumer socialization framework to understand electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) group membership among brand followers on Twitter. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 14(4), 251–260. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2015.04.002

Dimitrova, K. (2013, December 21). Woman fired after tweet on AIDS in Africa sparks Internet outrage. Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/International/woman-fired-tweet-aids-africa-sparks-internet-outrage/story?id=21298519

Ehrlich, B. (2011, February 3). Kenneth Cole’s #Cairo tweet angers the Internet. Retrieved from http://mashable.com/2011/02/03/kenneth-cole-egypt/

Farkas, K. (2014, September 15). Urban Outfitters issues an apology for selling red-splattered Kent State University sweatshirt. Retrieved from http://www.cleveland.com/metro/index.ssf/2014/09/urban_outfitters_issues_apolog.html

Freedman, L. (2016, September 22). The 12 worst social-media fails of 2016. Retrieved from https://www.entrepreneur.com/slideshow/272286

Gentle, A. (2013). Conversation and community: The social web for documentation (2nd ed.). Laguna Hills, CA: Xml Press.

Griner, D. (2014, September 9). DiGiorno is really, really sorry about its Tweet accidentally making light of domestic violence. Retrieved from http://www.adweek.com/adfreak/digiorno-really-really-sorry-about-its-tweet-accidentally-making-light-domestic-violence-159998

Hearit, K. M. (2006). Crisis management by apology: Corporate response to allegations of wrongdoing. Mahwah, NJ: Routledge.

Kador, J. (2009). Effective apology: Mending fences, building bridges, and restoring trust. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons, 53, 59–68. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

Kietzmann, J. H., Hermkens, K., McCarthy, I. P., & Silvestre, B. S. (2011). Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Business Horizons, 54, 241-251. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.005.

Kim, E., Sung, Y., & Kang, H. (2014). Brand followers’ retweeting behavior on Twitter: How brand relationships influence brand electronic word-of-mouth. Computers in Human Behavior, 37, 18–25. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.020.

KitchenAid. (2012, October 3). It was carelessly sent in error by a member of our Twitter team who, needless to say, won’t be tweeting for us anymore [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/KitchenAidUSA/status/253708391124459520

Marwick, A. E., & Boyd, D. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114–133. doi:10.1177/1461444810365313

McHugh, J. D. (2013, May 22). @karon @johndphoto I worded my answer terribly. I really apologize for what it sounded like outside of the context and notion of Flickr pro [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/marissamayer/status/337233311153938432.

McEachern, R. W. (2013). Social media challenges for professional writers. Journal of Current Issues in Media & Telecommunications, 5, 279–287.

Memmott, M. (2013, February 25). “The onion” apologizes for offensive Tweet about 9-Year-Old Quvenzhane Wallis. NPR. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2013/02/25/172884045/the-onion-apologizes-for-offensive-tweet-about-9-year-old-quvenzhane-wallis

Page, R. (2014). Saying ‘sorry’: Corporate apologies posted on Twitter. Journal of Pragmatics, 62, 30–45. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2013.12.003.

Lee, S., & Chung, S. (2012). Corporate apology and crisis communication: The effect of responsibility admittance and sympathetic expression on public’s anger relief. Public Relations Review, 38(5), 932–934. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.08.006.

LaCapria, K. (2013, November 7). Home Depot racist tweet causes controversy, company fires social media. Social News Daily. Retrieved from https://socialnewsdaily.com/19030/home-depot-racist-tweet-causes-controversy-company-fires-social-media-rep/11 Twitter brand fails. (2014, October 24). HLN TV. Retrieved from http://www.hlntv.com/articles/2014/10/24/11-twitter-brand-fails/

Tovey, J. (2003). Companies can apologize: Corporate apologies and legal liability. Technical Communication, 50, 420-421.

@UrbanOutfitters Twitlonger. (2014, September 15). Retrieved from http://www.twitlonger.com/show/n_1sagorq

Wasserman, T. (2014, September 9). DiGiorno pizza accidentally makes light of a domestic violence Hashtag. Mashable. Retrieved from http://mashable.com/2014/09/09/digiorno-pizza-whyistayed-hashtag/#qAcqawbczZqi

Wasserman, T. (2012, October 29). Gap criticized for insensitive Tweet during hurricane sandy. Mashable. Retrieved from http://mashable.com/2012/10/31/gap-tweet-hurricane-sandy/#uMRu5CoR5Gqd

Wessley, T. (2016). Managing social media chatter, complaints, conflicts and crises. Weidert. Retrieved from https://www.weidert.com/whole_brain_marketing_blog/bid/117503/Managing-Social-Media-Chatter-Complaints-Conflicts-and-Crises

Wheeler, R. (2012, September 14). Twitter fight, take Two: How Chipotle uses social media. River Front Times. Retrieved from http://www.riverfronttimes.com/foodblog/2010/03/17/twitter-fight-take-two-how-chipotle-uses-social-media

About the Author

Allen Berry received his PhD in creative writing from the University of Southern Mississippi in 2013 and a Certificate of Technical Writing from University of Alabama Huntsville’s Graduate Program in 2015. He currently teaches technical and business writing online for the University of Alabama Huntsville and Composition and Literature at South Georgia State College. He is the author of three collections of poetry. This is his first publication to appear in Technical Communication. He is available at jab0003@uah.edu.

Manuscript received 16 December 2016, revised 5 July 2017; accepted 12 September 2017.

Appendix 1

Twitter Apologies Examined for this Article

1) Urban Outfitters sincerely apologizes for any offense our Vintage Kent State Sweatshirt may have caused.

2) @KelloggsUK the cereal company posted ‘1 RT = 1 breakfast for a vulnerable child’

‘We want to apologise for the recent Tweet, wrong use of words. It’s deleted. We give funding to school breakfast clubs in vulnerable areas.’

3) @USAirways We apologize for an inappropriate image recently shared as a link in one of our responses. We’ve removed the Tweet and are investigating.

4) @DiGiorno: I stayed because you had pizza.

@ DiGiorno: A million apologies. I did not read what hashtag was about before posting.

5) IAC PR counsel: ““Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!”

Twitter Account Cancelled.

6) Marissa Mayer, Yahoo CEO: I worded my answer terribly. I really apologize for what it sounded like out of the context and notion of Flickr Pro.

7) LA Kings We apologize for the Tweets that came from a guest of our organization. They were inappropriate and do not reflect the LA Kings.

8) Gerald Scarfe has never reflected the opinions of the Sunday Times. Nevertheless, we owe major apology for grotesque, offensive cartoon.

9) KitchenAid, Obama Tweet: in one Tweet, she said that “I would like to personally apologize to President @BarackObama, his family and everyone on Twitter for the offensive Tweet sent earlier.” In another, she said the offensive Tweet was “carelessly sent in error by a member of our Twitter team who, needless to say, won’t be Tweeting for us anymore.”

10) Spaghetti O’s: “We apologize for our recent Tweet in remembrance of Pearl Harbor Day. We meant to pay respect, not to offend.”

11) Home Depot Racist Tweet apology: “We have zero tolerance for anything so stupid and offensive. Deeply sorry. We terminated agency and individual who posted it.”

12) AT &T: We apologize to anyone who felt our post was in poor taste. The image was solely meant to pay respect to those affected by the 9/11 tragedy.

13) Atlanta Journal Constitution apologizes for racist Tweet: The AJC apologizes for & deeply regrets the Tweet that was posted earlier today. We are working to address this situation internally.

14) Entenmann’s: Sorry everyone! We weren’t trying to reference the trial in our Tweet. We should have checked the trending hashtag in our Tweet.

15) Kenneth Cole: “Re Egypt Tweet: we weren’t intending to make light of a serious situation. We understand the sensitivity of this historic moment -KC”

16) Spinning Platters, Rashida Jones: Made a thoughtless comment about John Travolta. I sincerely apologize. Nobody’s personal life is my business.

17) Daniel Tosh: all the out of context misquotes aside, i’d like to sincerely apologize http://j.mp/PJ8bNs

18) Jason Kidd Drunk Driving: I regret any disruption my accident last weekend may have caused members of the community and want to thank the local authorities.

19) https://Twitter.com/LuisSuarez9/status/483659463417548800

20) Oprah Winfrey to Nielsen: “I removed the Tweet at the request of Nielsen. I intended no harm and apologize for the reference.”

21) Ashton Kutcher: The Tweet @aplusk wishes he never wrote? “How do you fire Jo Pa? #insult #noclass as a hawkeye fan I find it in poor taste,” dashed off on Nov. 10 after Kutcher heard that Paterno had been fired, but hadn’t heard why he had been fired. The worst kind of “oops.” Kutcher apologized profusely to his 8 million followers, Tweeted a picture of himself next to a sign saying “I’m with stupid,” and then announced he would be turning the management of his feed over to his publicists.

22) Alec Baldwin: Alec Baldwin was so incensed that he was asked to stop playing Words with friends on a flight between L.A. and N.Y. in early December that he couldn’t resist Tweeting it. “Flight attendant on American reamed me out 4 playing WORDS W FRIENDS while we sat at the gate, not moving. #nowonderamericaairisbankrupt.” The anger expressed in that Tweet, and a subsequent one that ended “#realwayisunited” gave the press something to pounce on, and by the end of the day, the story was everywhere. Baldwin later apologized for his behavior on Huffington Post and deactivated his Twitter account.

23) Patton Oswald, false Tweets: @pattonoswalt Oops. Just deleted my last Tweet. & would like to apologize to seniors & sufferers of Lyme disease. I was out of bounds.

@pattonoswalt Yikes. Had to delete another Tweet. I crossed a line on that one. Also, I thought 12 YEARS A SLAVE and THE BUTLER were brilliant.

http://www.funnyordie.com/lists/3a81fffa8e/patton-oswalt-angers-Twitter-idiots-with-fake-apologies

24) @NYPD25Pct Sincere apologies 4 insensitive & unprofessional Tweets. Not how I was raised, trained, have served. Will work 2 restore trust/confidence.

25) Fahmi Fadzil, sentenced to 100 Twitter apologies: 1/100 I’ve DEFAMED Blu Inc Media & Female Magazine. My Tweets on their HR Policies are untrue. I retract those words & hereby apologize

26) Stephen A. Smith: My series of Tweets a short time ago is not an adequate way to capture my thoughts so I am using a single Tweet via Twitlonger to more appropriately and effectively clarify my remarks from earlier today about the Ray Rice situation. I completely recognize the sensitivity of the issues and the confusion and disgust that my comments caused. First off, as I said earlier and I want to reiterate strongly, it is never OK to put your hands on a women. Ever. I understand why that important point was lost in my other comments, which did not come out as I intended. I want to state very clearly. I do NOT believe a woman provokes the horrible domestic abuses that are sadly such a major problem in our society. I wasn’t trying to say that or even imply it when I was discussing my own personal upbringing and the important role the women in my family have played in my life. I understand why my comments could be taken another way. I should have done a better job articulating my thoughts and I sincerely apologize.

27) French Journalist: 466 times In May, two French politicians won a novel conviction against a critic who had been calling them names on Twitter. In addition to paying a fine and court costs, the critic was ordered to Tweet the same message 466 times over 30 days: “I have severely insulted Jean-Francois Cope and Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet. I regret and apologize.”

28) Chipotle Media apology: Manager did the right thing. May be the only right thing on this visit. My apologies. Hope you’ll use the coupons to see us again. (Sat 13 Mar 3:54) http://blogs.riverfronttimes.com/gutcheck/2010/03/Twitter_fight_chipotle_uses_social_media.php

29) Soccer Player over infidelity scandal @_OlivierGiroud_ Ultimate precision with respect to my apologies…Yes I made a mistake but not I have not committed adultery! Things are clear… @_OlivierGiroud_ I apologise to my wife, family and friends and my manager, team-mates and Arsenal fans. http://bleacherreport.com/articles/1962149-olivier-giroud-issues-apology-on-Twitter-amidst-infidelity-scandal

30) Julianne Hough: “I am a huge fan of the show Orange Is the New Black, actress Uzo Aduba, and the character she has created,” Hough Tweeted. “It certainly was never my intention to be disrespectful or demeaning to anyone in any way. I realize my costume hurt and offended people and I truly apologize.”

http://www.twitlonger.com/show/n_1rqfec1

31) Southwest Airlines apologizes to Kevin Smith: @ThatKevinSmith hey Kevin! I’m so sorry for your experience tonight! Hopefully we can make things right, please follow so we may DM!

Hey folks – trust me, I saw the Tweets from @ThatKevinSmith I’ll get all the details and handle accordingly! Thanks for your concerns!

I read every single Tweet that comes into this account, and take every Tweet seriously. We’ll handle @thatkevinsmith issue asap

I’ve read the Tweets all night from @thatkevinsmith – He’ll be getting a call at home from our Customer Relations VP tonight.

@ThatKevinSmith Ok, I’ll be sure to check it out. Hopefully you received our voicemail earlier this evening.

@ThatKevinSmith Again, I’m very sorry for the experience you had tonight. Please let me know if there is anything else I can do.

@ThatKevinSmith We called you on the number you had on file in your reservation. If you prefer a different number, please DM me. Thanks!

Our apology to @ThatKevinSmith and more details regarding the events from last night – http://cot.ag/96KHC7 #Southwest http://mashable.com/2010/02/14/southwest-kevin-smith/

32) Belvedre Vodka: We apologize to any of our fans who were offended by our recent Tweet. We continue to be an advocate for safe and responsible drinking. http://observer.com/2012/03/belvedere-vodka-sort-of-apologizes-for-rapey-Twitter-advertising/

33) Gilbert Gotfried, Tsunami Tweet: @Therealgilbert I sincerely apologize to anyone who was offended by my attempt at humor regarding the tragedy in Japan.

@therealgilbert: I meant no disrespect, and my thoughts are with the victims and their families.

34) MMA Fighter, War Machine: @WarMachine170 I Tweeted something earlier that was stupid, insensitive and wrong. Rape is never something to joke about ever. I sincerely apologize. http://bleacherreport.com/articles/1734067-bellator-ceo-bjorn-rebney-issues-statement-on-war-machines-offensive-Tweet

35) Chiefs Apologizes to fan: @KCChiefs I apologize to the fans for my response to a Tweet sent to me earlier. No excuse for my actions. I am truly sorry and it won’t happen again. http://www.kshb.com/sports/football/chiefs/chiefs-apologize-for-angry-Twitter-message

36) Author Don Milleris apology for offensive blog post: So very sorry to have offended you and your friends. Very thankful for your tone. http://thoughtsbynatalie.com/2011/08/Twitter-apologies-gratitude.html

37) The Onion apologizes to Quivenze Wallis: “On behalf of The Onion, I offer my personal apology to Quvenzhané Wallis and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for the Tweet that was circulated last night during the Oscars. It was crude and offensive—not to mention inconsistent with The Onion’s commitment to parody and satire, however biting.

No person should be subjected to such a senseless, humorless comment masquerading as satire.

The Tweet was taken down within an hour of publication. We have instituted new and tighter Twitter procedures to ensure that this kind of mistake does not occur again.

In addition, we are taking immediate steps to discipline those individuals responsible.

Miss Wallis, you are young and talented and deserve better. All of us at The Onion are deeply sorry.”

38) Healthcare.gov apologizes: @HealthCareGov @elmnmd We apologize for the technical difficulties. We are working to fix these issues as soon as possible. Thank you for your patience!

http://www.nrcc.org/2013/10/01/obamacare-making-Twitter-timeline-healthcaregov-sad/

39) Pepsi apologizes for suicide ad: Huw Gilbert, Senior Manager for Communications at Pepsico, posted these replies:

@christinelu Huw from Pepsi here. We agree this creative is totally inappropriate; we apologize and please know it won’t run again. #pepsi

@christinelu @huwgilbert posted our response. My best friend committed suicide – this is a topic very close to my heart. My deepest apologies.

http://www.cbsnews.com/news/pepsi-apologizes-on-Twitter-for-suicide-ad-by-bbdo/

40) Durex Condoms apologizes: The Tweet read, “We wrote a post supporting Taeyeon and Baekhyun’s love. As idols getting public attention, it would not be easy to love. Durex supports all kinds of love. However, we found out that this support could greatly hurt the fans. We apologize.”