Avery C. Edenfield

Abstract

Purpose: While many organizations use ambiguity to strategically build a “unified diversity” around an organization’s mission, democratically managed organizations need to tread a narrow path between necessary ambiguity (which allows flexibility) and dysfunctional ambiguity (which causes disarray). To illustrate, I report a subset of findings regarding occasions when ambiguous documents had a significant impact on a democratically managed organization.

Methods: I conducted a three-phase study of a democratic cooperative. Using a mixed-methods approach, I sought to uncover the ways technical and professional communication (TPC) concerns like ambiguity and clarity function in a democratic business. In my analysis, I looked for patterns and dissonance between/among artifacts and participants, paying special attention to areas of ambiguity. Interviews and transcripts were analyzed alongside various genres using rhetorical analysis.

Results: Looking at two significant documents—job descriptions and bylaws—I found that ambiguity was rarely benign at Owen’s House. In the job descriptions, ambiguity rendered key positions dysfunctional and undermined the collective, resulting in a crisis. However, ambiguity in the bylaws allowed the collective to reinterpret organizational goals in support of necessary changes critical to achieving solvency.

Conclusion: When building unified diversity, democratic organizations must consider the positive and negative consequences of textual ambiguity. This consideration should extend to regulatory documents where clarity is often an assumed objective. Documents need to be flexible enough to adapt to changes and defined enough to avoid sliding into dysfunction.

Keywords: ambiguity, communication, texts, bureaucracy, cooperative

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Overview: Though documents in a democratic organization may look like those created by a conventional firm, these documents may function differently for three reasons. First, in the absence of a primary decision-maker or a hierarchical structure, regulatory texts act as a framework for the organization. Second, these jointly written texts must balance ambiguity and precision. Third, in such a unique workplace, ambiguity is not always benign and can either be debilitating or constructive.

- Implication 1: The efficacy of strategic ambiguity is subject to the following conditions: the text addresses an individual vs. the collective, the text addresses the abstract vs. the concrete, the scale of the organization is small vs. rapidly growing or large.

- Implication 2: Strategic ambiguity in regulatory documents challenges the assumed need for clarity and precision in documentation.

Introduction

Many organizations strategically use ambiguity; documents often contain content that is “ambiguous and unclear,” yet, successfully balancing ambiguity and precision can create a “unified diversity” (Contractor & Ehrlich, 1993; Eisenberg, 1984) among stakeholders, e.g. building consensus on abstract principles and allowing multiple parties to claim victory (Davenport & Leitch, 2005; Paul & Strbiak, 1987, p. 149). Overly precise texts may lack flexibility and may require a clear agreement by all parties (Davenport & Leitch, 2005; Eisenberg, 1984). Most of the organizational communication scholarship around ambiguity focuses on mission statements and goals because vague language in regulatory texts, such as job descriptions or codes of conduct, may render the organization dysfunctional. However, in democratically managed firms, which operate without hierarchy and instead rely on consensus, ambiguity may extend to documents intended to regulate behavior. These organizations may need to tread a narrow path between necessary ambiguity (which allows flexibility) and dysfunctional ambiguity (which causes disarray). This need for additional ambiguity may extend beyond abstract principles to regulations.

Given the absence of structure that a central decision-maker provides and that vague language affords multiple interpretations, ambiguity may be an important mechanism for bringing people to consensus in order to work together. This may be true even with regulatory texts, where achieving a balance of ambiguity is crucial because of the text’s dozens of decision-makers of equal authority and a cacophony of voices, motives, and values. In a democratic workplace, a precisely worded, prescriptive document would require a unanimous interpretation that may be difficult if not impossible to achieve. Strategic ambiguity in regulatory documents challenges the assumption of the necessity of clarity and precision prevalent in technical and professional communication (TPC). I argue that ambiguity in collaboratively written, regulatory texts plays a crucial—and problematic—role in business operations for at least three reasons. First, in the absence of a primary decision-maker or a hierarchical structure, writing acts as a framework for the organization, holding it together. Second, and related to the first, jointly written governing texts must walk a thin line between nebulous ambiguity and precision. Third, ambiguity in such a unique workplace is not always benign and can be either debilitating or constructive.

This article reports findings from an examination of one type of democratic business. In order to better understand the role of writing in such a unique organization, I studied Owen’s House Cooperative (all names, locations, and other identifying information have been changed), a business best described as a community space operating as a pub. During my two-year study, the business experienced a significant crisis, in part due to ambiguity. In one situation, I witnessed textual ambiguity inhibit the organization. In another, ambiguity helped the organization recover. Writing practice was a key factor in each scenario.

To share these results, I begin with an overview of hierarchy and workplace texts, democratic control and cooperatives, and strategic ambiguity and its defining attributes. Then, I describe my research study and examine two foundational documents: a job description and the organization’s bylaws. Finally, I share my findings, namely that democratically managed organizations may strategically use ambiguity in regulatory documents to allow for flexibility and to encourage ongoing dialogue among those involved, and that this ambiguity can either debilitate an organization or create an opportunity to evolve. I conclude with two implications of this research for TPC scholars and practitioners.

Literature Review

In the sections below, I provide an overview of the relationship between hierarchical control and texts relevant to TPC. Then, I introduce cooperatives as an example of an organization that values democratic control. Because of their commitment to democratic control and related values that ambiguity may undermine, cooperatives are critical locations for studying strategic ambiguity.

Hierarchy and Workplace Texts

TPC has long documented the relationship of technical communication to hierarchical organizations, characterized by “centralized decision making,” “scaler chains of communication,” and predictable behavior (Harrison, 1994, p. 249; see also Longo, 2000; Zuboff, 1988). Harrison (1994) declared that the very idea of management is “inseparable from hierarchical connotations” and that top-down, command-and-control is nearly ubiquitous (p. 249; see also Kastelle, 2013). For the past two decades, TPC scholarship has called attention to the role documents play in maintaining such structures. For example, Winsor (2003) examined the role of documentation in an engineering facility and found that even a mundane document like a work order functioned to maintain superior-subordinate positions. Also, Zachry’s (2000) study of the Rath Packing Plant found that stable genres came to act in service of maintaining hierarchies at the organization and control over peoples’ work activities, identities, and positions within the company (pp. 65, 66, 68).

Concurrently, in the past few decades, scholars have also begun to look to alternative organizations that shift power from a top-down, command-and-control style management to team-based, bottom-up management. Scholars are also considering how this decentralized work affects employee agency, communication, and productivity (Clark, 2006; Johnson-Eilola, 1996; Spinuzzi, 2013, 2014, 2015; Wilson, 2001). Within this research, some have focused on deployment of the rhetorics of empowerment, i.e., persuasive language of greater employee agency and decision-making power. In part, they have debated about whether this language of greater employee agency is actualized or if it is simply operationalized to gain consent toward greater productivity and buy-in without the materialization of rewards (Clark, 2006). In Faber’s (2002) study of community action and rhetoric, he quotes Gee, Hull, and Lankshear (1996):

[They] argue that the rhetoric of new capitalism is ‘insulting to workers’ despite its desire for fully informed and participatory employees…employees cannot actually engage in such behavior if the consequences are detrimental to the organization. The employees only have agency insofar as this agency acts in the interests of the company. pp. 64–65

As Clark, Faber, and Gee, Hull, and Lankshear demonstrate, rhetorics of democratic participation and employee empowerment can be a powerful motivator but may lack a realization of democracy.

Despite these scholars taking note of some of the issues these flatter, distributed, networked or unconventional organizations may encounter (Gee, Hull, & Lankshear, 1996; Johnson-Eilola, 1996; Kastelle, 2013; Robertson, 2015; Spinuzzi, 2013, 2014, 2015; Waterman Jr., 1990), there is still scant research on technical documentation and writing practice in democratic organizations, the kind of organizations that intentionally reject hierarchy. In contrast to top-down and command-and-control operation, these organizations operate with unique features. Some of these features may include shared decision making, fewer levels of supervision, some form of consensus process, and greater employee participation and ownership than conventional, hierarchical systems (Cheney, 1995; Craig & Pencavel, 1995; Fakhfakh, Perotin, & Gago, 2009; Harrison, 1994). At times, these organizations may also experience instability or paralysis (The Cooperative Movement, 2013, p. 11). Writing may play a strategic role in working through these barriers.

Cooperatives

Sometimes described interchangeably as “bottom-up,” “flat(ter),” or “horizontal,” cooperatives are one type of democratic organization that may try to actualize ideals of empowerment that Clark (2006), Faber (2002), and others identified. The International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) defines a cooperative as “an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise” (ica.coop). Constructed by and for its members, a cooperative challenges basic tenets of conventional businesses, such as top-down exertions of power; the separation between investors, users, and employees; and the notions of shared ownership. In a cooperative, ideally, democratic values are translated into business principles and then upheld through the organization’s self-definition, structure, and culture. Importantly, advocates are careful to point out that it is democratic control and a de-prioritization of profit at the expense of other values that sets the cooperative model apart from other conventional organizations (Cheney, 1995; Williams, 2007). Ideally, the cooperative model seeks to balance profit with the needs of the communities they serve (Williams, 2007; Zeuli & Cropp, 2004).

In the case of the cooperative I studied, and many like it around the world, organizational identity is rooted in democratic control. This ideal is realized through shared governance and expressed in the documentation that the governed themselves create. It is also a defining feature of democratic management. That is, rather than ownership and control resting in the hands of investors or shareholders, the control rests with the multiple owners of the cooperative, also known as the “one person, one vote” principle (Zeuli & Cropp, 2004, p. 45; see also Cheney, 1995; Pittman, n.d.). The foundational principles of democratic control are traits all cooperatives share to a degree (Cheney, 1995):

- Some commitment to collective if not necessarily equal ownership by members

- Some commitment to democratic decision making by members

- A belief in the viability of like experiments outside of their own experience (p. xiv; see also, Pittman, n.d.).

Along with other locally contingent values, these commitments shape the cooperative to the needs of the community. Cooperatives offer a crucial setting in which to study ambiguity, because they are constructed from the ground up around unity, participation, and shared vision—values ambiguity can undermine (Eisenberg, 1984).

Strategic Ambiguity

Davenport and Leitch (2005) defined strategic ambiguity as “the deliberate use of ambiguity in strategic communication in order to create a ‘space’ in which multiple interpretations by stakeholders are enabled and to which multiple stakeholder responses are possible” (p. 1604). For Eisenberg (2007), strategic ambiguity is “the human capacity to use the resources of language to communicate in ways that are both inclusive and preserve important differences” (p. x). Drawing from a range of scholarship, Eisenberg and Goodall (1997) “…described four characteristics of strategic ambiguity.” First, strategic ambiguity fosters “unified diversity,” attempting to unite multiple viewpoints and build “agreement on abstractions” (Davenport & Leitch, 2005, p. 1606; see also Eisenberg & Goodall, 1997). As such, “[s]trategic ambiguity is often found in organizational missions, goals and plans, allowing divergent interpretations to coexist and enabling diverse groups to work together” (Eisenberg & Witten, 1987; see also Davenport & Leitch, 2005, p. 1606; Eisenberg, 1984, p. 230; Eisenberg, 2007). Second, strategic ambiguity upholds privilege by “shielding the powerful” (Davenport & Leitch, 2005, p. 1606; Eisenberg & Goodall, 1997, p. 24). Third, “strategic ambiguity is deniable” so that language that seems “to mean one thing” can, under strain, “seem to mean something else” (Davenport & Leitch, 2005, p. 1606; Eisenberg & Goodall, 1997.) Finally, strategic ambiguity “facilitates organizational change by enabling shifting interpretations of organizational goals” (p. 1606; see also Eisenberg & Witten, 1987; Eisenberg & Goodall, 1997, p. 24). These four attributes define the function of ambiguity in an organization and show why ambiguity in a democratic setting may be problematic.

Although approaches to ambiguity as a resource have not been explored in a democratically managed organization, research points to the tension between ambiguity as a struggle for consensus, a potential method for redirecting ethical responsibilities, and as a resource for building consensus among various stakeholders for collective action (Davenport & Leitch, 2005; Eisenberg, 1984; Jarzabkowski, Sillince, & Shaw, 2010; Paul & Strbiak, 1987). Most notably, strategic ambiguity is often reserved for abstractions like mission statements or declarations of company values and goals, statements where higher-order agreement is needed without limiting details.

Method

For this IRB-approved study (14.301), I researched communicative practice in a democratically operated cooperative bar for two years, guided by the following research questions:

- What are the differences and similarities in writing practice between a conventional business and a democratic business like a cooperative?

- Do TPC concerns like ambiguity and clarity emerge and function differently in a democratic business than they do in a conventional business?

Answering these questions is important for least two reasons. First, this research will begin to fill the gap of scant research on rhetorical practice in democratic businesses. Second, considering the recent turn toward social justice in TPC (Agboka, 2013; Agboka, 2014; Colton & Holmes, forthcoming; Colton & Walton, 2015; Jones, 2016; Jones, Moore, & Walton, 2016; Walton, Colton, Wheatley-Boxx, & Gurko, 2016) and because writing is key to good organizational practice, researchers and practitioners may consider offering support to democratically owned businesses. Cooperatives are one strategy marginalized communities have used for self-advocacy, “economic defense,” and “collective well-being” (Gordon Nembhard, 2014, p. 1). Such community-embedded organizations are rich sites for technical communicators to conduct mutually beneficial research projects and to enact social justice.

I conducted my research in three phases over a two-year period, from 2014–2016. First, for about six months, I conducted secondary and background research, selected a site, and recruited participants. Second, for the next six months, I collected data. Finally, I conducted analysis and disseminated my research. As with any study, this article discusses one aspect of a larger project. Below, I discuss my research methods and methodologies in more detail.

Phase 1: Preliminary Research, Site Selection, and Recruitment

In Phase 1, I began preliminary research on U.S. cooperative theory and practice. I collected and reviewed regulatory and other organizational documents from U.S. cooperative websites and then analyzed this documentation through research on strategic ambiguity and genre theory. I also observed two cooperative conferences coinciding with my study, one in Madison, WI, and one in Chicago, IL. My preliminary research focused on U.S. cooperatives with a commitment to workplace democracy and shared ownership. I excluded non-U.S. cooperatives, large agricultural cooperatives, energy cooperatives, large consumer cooperatives, traditional organizations with an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP), and other cooperatives that did not express a commitment to workplace democracy or shared management.

Site I identified Owen’s House Cooperative as a prime location to study democratically managed organizations for a number of reasons. Because it was a relatively new cooperative, many of its founders continued to be involved either as employees, board members, or volunteers. Additionally, they had created and were willing to share documentation dating back years. Most importantly, unlike other cooperatives in the area, Owen’s House was operated through shared management by the Board of Directors and the staff. This business was designed from its founding as a democratically managed operation.

Choosing a pub as a site of investigation of communicative practice required broadening my understanding of what TPC research does and who it is for. I understand Owen’s House as a legitimate site for research for at least two reasons. First, work by TPC scholars has shown extra-institutional communication as a legitimate and complex area of research (Bushnell, 1999; Johnson-Eiola, 2004; Kimball, 2006). As Berlin (1988) argued, research is “always already ideological” (p. 477; see also Alvesson, 1991; Blyer, 1995; Harrison, 1994; Herndl, 1991, 1993), including what sites researchers hold as legitimate (Harrison, 1994, p. 248).

Although many researchers acknowledge that bureaucratic arrangements are not the only form of organization, research “nevertheless appears to take the model for granted” (Harrison, 1994, p. 249). Research that includes non-expert sites—where ordinary people produce documents for the exchange of technical information—acknowledges a broader understanding of how people communicate (Kimball, 2006). An in-depth study of a democratically managed organization may necessitate broadening our scope to alternative organizations. Secondly, and related to the first point, the people of Owen’s House understood that what they were building was first and foremost a political project and a backdrop to their mission of community development (Bylaws, 2011). Owen’s House was designed to be a community space serving a neighborhood (Sean, personal communication, June 24, 2014; Patty, personal communication, July 14, 2014). One founder, Patty, said that Owen’s House was founded in the tradition of European public houses renowned for political organizing. Another founder, Sean, described Owen’s House as “more than a bar.” That Owen’s House was a political project is an important detail because the founders were motivated by democratic commitments and community relationships, rather than profit or other entrepreneurial motives.

Per bylaws and original documents, Owen’s House was designed to be a hybrid structure, merging a consumer and employee cooperative (Bylaws, 2011). In a consumer cooperative, owners of the cooperative are users who buy shares and are entitled to voting rights and discounts or dividends (Gordon Nembhard, 2014, p. 3). In contrast, in an employee cooperative, the workers themselves own all the shares, sit on the Board of Directors, and control the business (Gordon Nembhard, 2014, pp. 3–4). Opening as a consumer cooperative gave Owen’s House founders access to start-up capital without going into debt while operating as an employee collective harmonized with their commitment for shared governance (Patty, personal communication, July 14, 2014). Management at Owen’s House consists of the Workers Collective and the Board of Directors, the latter bearing fiduciary responsibility. The Workers Collective is a group of 10-20 employees, many of whom actively participate in making decisions. Originally, the Workers Collective included four leadership positions called “auxiliary positions,” described in Table 1 (Job Descriptions & division of labor for the [Name Redacted] Workers Collective; Introduction to Workers Collective, 2012).

Table 1. Auxiliary positions in the workers collective

| Auxiliary Position | Role and Responsibilities | Accountable to |

|---|---|---|

| Lead Bartender | Act as pseudo-manager | Board of Directors/Workers Collective |

| Inventory Coordinator | Maintain proper inventory levels | Board of Directors/Workers Collective |

| Event Coordinator | Recruit and manage events | Board of Directors/Workers Collective |

| Financial Coordinator | Manage finances and payroll | Board of Directors/Workers Collective/ Special Finance Committee comprised of select Directors |

The Workers Collective and auxiliary positions were responsible for the daily operations of the bar (Bylaws, 2011). In addition to interfacing with consumer-owners and the community, the Collective worked with the Board of Directors, a group of nine members who decided on larger issues including budgets, large spending projects, and community relations (Bylaws, 2011). State law dictates a Board’s responsibilities, as a cooperative’s Board of Directors is legally accountable “for the co-op’s continued viability” and answers to the consumer-owners (Zeuli & Cropp, 2004, p. 50). Consumer-owners meet once a year at an Annual General Meeting with the Board of Directors and Workers Collective.

Recruitment

I recruited past and present employees, volunteers, and board members. I recruited on site in March 2014 using a variety of methods: presenting my potential research project in meetings of the Workers Collective and Board of Directors and emailing past Owen’s House participants whose names were given to me by current participants. Consent was obtained on site during one week in April 2014 or, in the case of former members, prior to the interview.

Phase 2: Data Collection

In the second phase of my study, I collected data through artifact collection, observation, and interviews.

Artifact collection

Pursuant of my research questions and my assumption of written communication as critical to operations (especially in a democratically managed organization), I solicited artifacts from participants related to workplace communication and project management, collaboration, information sharing, and training. I also requested artifacts dating back to the founding of the organization. Collected artifacts included meeting notes from the Workers Collective and Board of Directors, project to-do lists, emails, text messages, training documentation, bylaws, handbooks, inventory lists, event notes, and screenshots. Most artifacts were in digital form on Google Docs, which could be easily shared. To ensure the privacy of others, participants were invited to redact personal identifying information from the artifacts before turning them over to me.

Observation

With participants’ consent, I observed multiple meetings of the Board of Directors and Worker Collective, as well as two special sessions. The sessions I observed included:

- Bi-weekly staff meetings where the day-to-day decisions were made

- Monthly (or bi-weekly) meetings of the Board of Directors

- Emergency special sessions during the financial and personnel crisis.

These last meetings were convened to tackle the previously mentioned crisis (Special Finance Meeting, 2014 April 6) and a small number of meetings of volunteers who crafted the Workers Collective response to the crisis (Leadership Meeting, 2014 April 16). In each of these meetings, I took detailed notes on the verbal and nonverbal communication between participants and paid special attention to the way texts were cited, reviewed, or otherwise operationalized.

Interviews

To gain insight into people’s motives, histories, and activities at Owen’s House, I conducted five interviews with past and present staff and members of the Board of Directors, conducted over a five-month period. Interview participants were chosen if they were over 18 and met at least one of the following criteria:

- Employed by Owen’s House for longer than one year

- Involved in some facet of management

- Involved in the early developmental stages of the bar.

Interviewees featured in this article—Sean, Patty, Levi, Lucas, and Robert—met all three criteria. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. Each interview began with a series of pre-written questions, including asking about past and present decision-making processes, the collaboration process, and the exigence of the texts that had been collected. Regarding the composition and institution of texts, I was especially interested in learning more about authorship and context, and about the composing process itself, e.g., did participants collaborate on the document, or was there a single author who disseminated a text for feedback and revisions? Were documents adopted whole cloth or was there a revision process? Answering these questions would help to understand how participants navigated ambiguity in their communication.

Phase 3: Analysis

In my analysis, I looked for patterns and dissonance between/among artifacts and participants, paying special attention to areas of ambiguity in the documents and how participants navigated that ambiguity in their interactions. Interview transcripts were analyzed alongside various genres using rhetorical analysis (Jarzabkowski, Sillince, & Shaw, 2010). A rhetorical analysis allows an examination of the consequences of the texts and contends that group behavior is delimited temporally through genres, understood by many contemporary rhetoricians as typified social responses to typified social situations (Miller, 1984; Winsor, 2003, 2007). As such, genres are a powerful stabilizing tool or, as Schryer says, “stabilized-for-now” as the genre and its effects are always in flux (1994; Winsor, 2007, p. 3). That is, a rhetorical analysis of a genre would focus more on its affordances (what actions does this genre allow/disallow?) rather than its taxonomic features. To understand how a text becomes a genre and how ambiguity affects its use, we can look at what situations those texts respond to. If these generic texts render relationships stable and help to regulate actions of heterogeneous work groups (Devitt, 1992; Miller, 1984; Winsor, 2007), then it may be important to understand how ambiguity either supports or undermines that work.

Consistent with qualitative, action, sociocultural, and ethnographic research methods in workplace writing studies, I was both an observer of and participant in my research site (Doheny-Farina, 1993; Berlin, 1988; Clark, 2006; Herndl, 1991, 1993; McNely, Spinuzzi, & Teston, 2015; Spinuzzi, 2005; Walton, Zraly, & Mugengana, 2015). All researchers “participate in the activities they articulate and in the articulation of those activities” (Clark, 2006, p. 164). Even our “presence alone” can affect what participants say and do (Doheny-Farina, 1993, p. 255). In my case, my participation was further complicated, because I was hired by Owen’s House, joining the Workers Collective in 2012. In May of 2013, I was elected in a blind vote by members and colleagues to serve on the Board of Directors. TPC scholarship has shown that all researchers are implicated in and participate in their research sites and that no researcher is ever a neutral observer (Clark, 2006; Doheny-Farina, 1993; Herndl, 1991). Nevertheless, being an embedded researcher came with affordances and constraints. Being embedded allowed me to not only look at the texts they produced and used but also to gain understanding in their cultural frames, community norms, and other aspects of writing culture in ways I could not have accessed otherwise.

My position as a researcher and a member of the Collective and Board challenged my relationship with my coworkers and co-directors in at least two ways. First, they trusted me, and my excitement for the project in its early stages may have encouraged them to share information with me they may not have otherwise shared. Their trust in me led to ethical quandaries, such as how to faithfully represent personal conflicts among staff or board members, if or when to redact information when participants refused or neglected to, or how to convey the seriousness of my project to them when I was both one of them and an observer of their work (Clark, 2006, p. 164.). One way I dealt with these issues was to regularly remind participants of their rights in the project, that they may speak off the record or withhold documents from the study, and that others would be reading the work I was producing. Second, because of my relationship with participants, the fragility of the new business, and the tenuous position of cooperatives as an alternative economic model for marginalized communities, critique was sometimes difficult. To deal with this problem, I sometimes shared preliminary findings to solicit feedback. Anonymizing the data, I also discussed my findings or critiques with trusted colleagues and experienced cooperative organizers whose comments on the project were invaluable.

Strategic Ambiguity at Owen’s House

Many organizations purposefully practice ambiguity to foster a “unified diversity, to gain buy-in from various stakeholders with diverse—and possibly even competing—values, motives, and goals, and to allow for flexibility and contingencies (Eisenberg, 1984, 2007; Eisenberg & Witten, 1987; Jarzabkowski, Sillince, & Shaw, 2010; Paul & Strbiak, 1997). However, for democratic organizations where 1) documents replace hierarchy as an organizational framework, and 2) a myriad of actors have a say in the writing and execution of a text, even regulatory documents like bylaws, codes of conduct, or handbooks must achieve a balance between ambiguous and prescriptive. In the case of Owen’s House, I found strategic ambiguity extended into texts intended for regulating behavior. That is, the need for prescriptive rules and meaningful regulatory documents were balanced with the need for diplomacy and consensus among members who equally shared decision-making power. This need for ambiguity is imperative, because, unlike a conventional organization where precision and clarity are key, ambiguity forced ongoing negotiations of meaning, in line with their democratic commitments outlined above. This unique writing strategy may problematize the assumed need for clarity.

Nevertheless, ambiguity was not always benign and in fact created trouble for an already tenuous organization. Despite the way ambiguity allowed diversity among participants (Eisenberg, 1984), I also found ambiguity placed a unique strain on documents. Specifically, key organizational documents of job descriptions and the bylaws became the focus of tensions between ambiguity and precision, resulting in a significant crisis and, ultimately, a reorganization of the business. The crisis and resolution demonstrate that ambiguity can be both dysfunctional and a tool for organizational change.

Crisis

In April 2014, a personnel and financial emergency threatened to close Owen’s House, brought on in part by ambiguous job descriptions, lack of clear oversight, and vague divisions of labor (Lucas, “A Couple of Issues…”; Special Finance Meeting, April 4, 2014). Acting lead bartender, Lucas reported that duties crucial to solvency were handled redundantly or, sometimes, not at all. In meetings and in correspondence, participants reported that three of the four auxiliary positions in the Workers Collective—Lead Bartender, Inventory, and Finance—were misaligned with other positions. This incongruence resulted in misinterpretation of their vague job descriptions, or, for reasons beyond the scope of this article, not completing their duties at all. At an emergency meeting of the Board of Directors, and then in an open meeting with employees and staff, the group consented to a re-organization of management (Board of Directors, April 12, 2014; Special Finance Meeting, April 4, 2014). Working collaboratively and through long hours, the Board of Directors and the Workers Collective resolved the crisis in two ways. First, to address dysfunctional ambiguity, job descriptions were revised in service of an arrangement that consolidated positions into a team of two co-managers. These two positions would oversee business operations through clearly delegated job responsibilities (Leadership Meeting, April 16, 2014; Divvyed Job Descriptions). Second, capitalizing on the affordance of flexibility that strategic ambiguity allowed, bylaws came to be interpreted in service of this new arrangement (Special Finance Meeting, April 4, 2014).

Job Descriptions: Revised for Precision

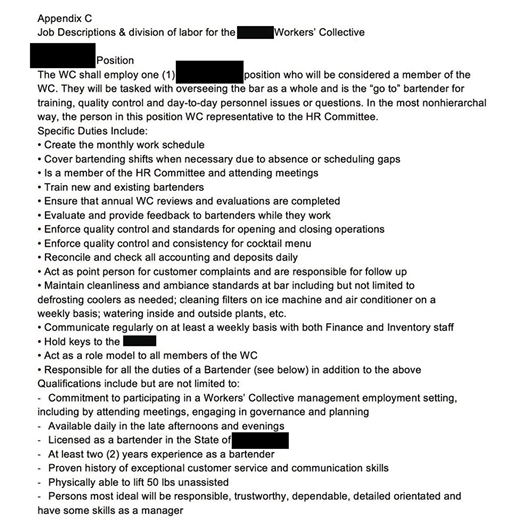

Members recognized ambiguous job descriptions as a critical failing point (Special Finance Meeting, April 4, 2014). This problem is to be expected as delineating initial roles and responsibilities for positions was a significant struggle for the new cooperative as founders sought to strike a balance between their need for structure and their democratic commitments. Those involved in the earliest stages were divided on how the workforce should be structured. According to interviews, because they were ideologically opposed to top-down management, they struggled with defining the work and creating roles and responsibilities for themselves while maintaining their commitment to shared management (Levi, Robert, Patty). The creation of the Workers Collective in the bylaws was a step toward realizing their ideological commitment of shared management (Sean; Bylaws, 2011). The group’s first demarcation of job responsibilities, “Job Descriptions & division of labor for Owen’s House Workers Collective,” especially the important position of lead bartender, is evidence of how the document sought to strike a balance between regulation and autonomy. The one-page document lists responsibilities, expectations, and requirements of the job.

Shown in its entirety, this list of conventional managerial duties reflects a concern to incorporate some of the necessities of such a position; however, overall, the document is vaguely worded (see, for example, “have some skills as a manager” and the title “Lead Bartender”). The authors also placed limits on that authority through phrasing like “in the most nonhierarchical way,” “act as a role model,” and “commitment to participating in a Workers’ Collective management employment setting.” Noticeably missing are any consequences, quantifications of the expectations or job duties, mechanisms of review or oversight by the Board of Directors, or a clear delineation of how this job would interface with other positions. Rather, this description demonstrates concerns for how participants’ writing reflected their democratic commitments and shaped the structure they were building together, even if it folded in rather conventional and even hierarchical bar manager activities, marked by words like “enforce” and “evaluate.” Similar to the description for lead bartender, all job descriptions were designed to be nimble. The expressed intention behind the ambiguity was that the person occupying the position would govern their duties in response to changing organizational needs and contexts, and that this person would be in constant conversation with others (Patty).

Nevertheless, over time, the lack of clarity of how positions interfaced with each other became a greater problem. For example, by the time of the crisis, both the financial officer and the lead bartender began to cover the same duties (Board of Directors, April 12, 2014). The inventory coordinator, finance coordinator, and lead bartender redundantly handled inventory and bookkeeping (Special Finance Meeting, April 6, 2014). Thus, some bills went unpaid because, although it was clear who was supposed to pay the bills, it was not clear who was ultimately responsible for making sure payment was made (Board of Directors, April 12, 2014; Lucas, “A Couple of Issues…”). When the job description for lead bartender clashed with material conditions, the document failed in perhaps unexpected ways. Because of ambiguity in the original description, the person filling the role had to do significant interpretation on his or her own of what was expected of him or her.

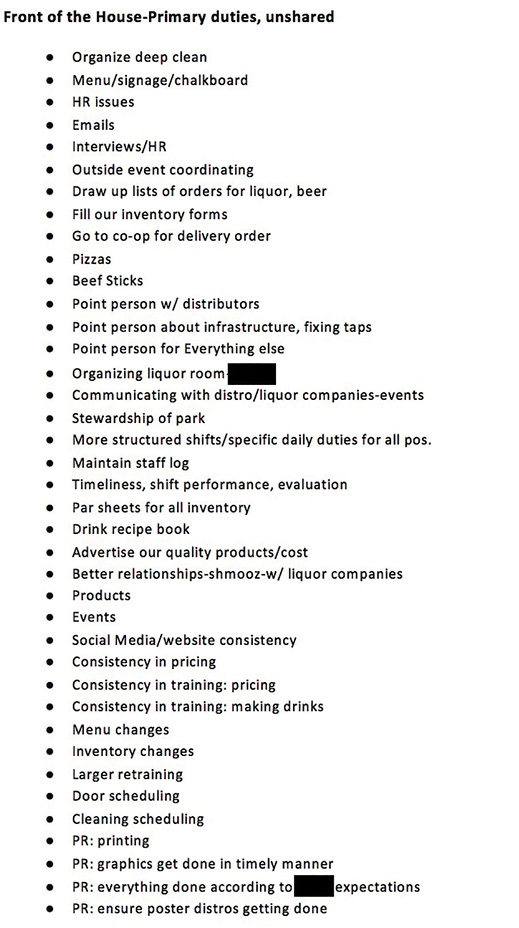

In response to the crisis, Owen’s House’s resolution consolidated the lead bartender, inventory, and financial positions into two co-managers: a Front-of-the-House (FotH) position who would manage the “front-facing” aspect of the business (staff training, inventory, aesthetics, vendor relations, and other concerns) and a Back-of-the-House (BotH) position who would manage finances and other concerns that took place outside of customers’ view (Leadership Meeting, April 16, 2014). Working together, workers who had previously held those positions re-wrote their own job descriptions and clearly outlined duties for each position (Special Finance Meeting, April 6, 2014). Below is a short excerpt of the expanded job description of FotH, now a five-page document with clearly delineated job duties and responsibilities for each position. For example, whereas in the old description, the lead bartender was vaguely tasked with “overseeing the bar as a whole,” the new description clearly outlined the perimeters of oversight for this position.

Figure 2. Leadership meeting-divvyed job descriptions, updated 4.26.14

The authors substituted ambiguity with precision, clearly demarcating responsibilities for each position and specifying how they would report to each other and to the Board. In a move from all-hands-on-deck management, the new positions would visibly act as a diarchy. Consolidating the positions centralized decision-making power and expanded FotH and BotH oversight over other workers. Therefore, the new job descriptions fell into tension with the concept of broad participation in management activities. Whereas the lead bartender was understood as a worker among workers, FotH and BotH were understood as supervisory positions (Board of Directors, April 26, 2014). In that same meeting, Will explained the new positions as “enforcers,” saying “Workers collective has no shortage of great goals and great ideas, but where we need the GMs [general managers] is to enforce these. Workers Collective decides the what, and the GMs decide the how” (Board of Directors, April 26, 2014). Although the new structure resolved the problems engendered by ambiguity, this structure represented a move away from collectivity to a tandemocracy (Hale, 2009) and put their most foundational documents in jeopardy, namely their bylaws.

Bylaws: Reinterpreted for Change

In Owen’s House’s home state, the statute establishing the legal existence of a cooperative requires the creation of bylaws by a proto-Board of Directors. After the cooperative is established, bylaws can be changed by a member vote, a procedure outlined in state statute. For Owen’s House, as with many cooperatives, bylaws were one of the first documents created and represent one of the earliest compromises by the newly formed organization.

Bylaws are significant documents for at least three reasons. First, they define the organization’s mission, trajectory, and internal structure (Hampton). Second, bylaws are legal documents that inaugurate the cooperative at the state level. For the organization to legitimately exist and to participate in all the legal activities required for operation (e.g., obtaining a license, workers compensation, and insurance), these documents must be crafted and authorized by the state. Third, Owen’s House’s bylaws established the creation of the Workers Collective, representing a first step toward manifesting organizers’ shared value of collective management (Bylaws, 2011).

Owen’s House’s bylaws had a material, constant presence in the cooperative. I observed bylaws being turned to again and again whenever there was a dispute over an interpretation. For example, in one meeting of the Board of Directors, a director reminded the Board that the bylaws stated a person for a specific role had to be a member of the Board (Board of Directors, July 22, 2014). In another meeting (Board of Directors, May 13, 2013), the bylaws were consulted when considering how many members of the Workers Collective could hold a seat on the Board. But the most significant test of the bylaws came in re-organization and installation of the two co-managers.

The second article, the “Statement of Purpose,” defines the cooperative’s purpose. Owen’s House

. . . seeks to uphold cooperative standards of democracy, equality, self-responsibility, equity and solidarity and strives to operate in accordance with the values of collective worker management, living wages, strong community involvement, safe environment, responsible drinking and local products. (Bylaws, 2011)

In a clear example of strategic ambiguity, the authors refrain from defining precise meanings of fraught terms like “equality,” “self-responsibility,” “collective management,” or “safe environment,” and instead allow meaning to be determined in context. Leaving key terms to interpretation allowed for a unity around their organizational mission and created a framework for coordinated action.

The re-organization of the auxiliary positions as a result of the crisis highlighted the tension between ambiguity operationalized as unified diversity and ambiguity leading to dysfunction. During the transition, the implication of the term “collective management” was fiercely debated. Related to this conflict, directors discussed whether a change was in line with the “values” of collective management and how that value could be realized in the new positions (Board of Directors, April 6, 2014). Directors identified the necessity of updating the bylaws to reflect the organizational changes they were considering and thus the need to make these changes transparent to member-owners, as bylaws could only be changed through member vote (Special Finance Meeting, April 6, 2014; Board of Directors, April 26, 2014). However, rather than changing the bylaws through a vote, eventually, bylaws became reinterpreted in light of new organizational needs. That is, they came to be read as “supporting collective management,” and the placement of two co-managers came in line with this view of collective management. The changes were never officially recorded, but rather, over time, the bylaws were interpreted in a different manner than before, in service to new organizational needs, and as supporting collectivity in the abstract sense rather than a literal interpretation.

Both the bylaws and the job descriptions capitalized on strategic ambiguity. To recall, Eisenberg identified four traits of strategic ambiguity:

- Fosters unified diversity

- Maintains privilege by “shielding the powerful” from examination

- Upholds deniability

- “Facilitates change by enabling shifting interpretations” (Davenport & Leitch, 2005, p. 1606; Eisenberg, 1984, 2007; Eisenberg & Goodall, 1997; Eisenberg & Witten, 1987).

Initially, the job descriptions bore the first trait, but they became dysfunctional by not defining limits to each job. Rewriting the documents for precision and eliminating ambiguity was an exercise in putting forth a specific interpretation rather than allowing the person who held the job to interpret their position per changing needs. Bylaws, however, embodied traits one and four as they used ambiguous language to impose a needed change and obtain the consent of those involved by allowing for multiple interpretations of the word “collective.” Ambiguity in the bylaws strategically enabled the Board to act quickly to enact a change that may have ultimately saved the business.

Conclusion and Implications

When building unified diversity, democratic organizations must carefully consider the consequences of textual ambiguity. That is, documents need to be not only flexible enough to adapt to changes but also defined enough to avoid sliding into dysfunction. At Owen’s House, ambiguity caused confusion among workers’ duties yet created a path to solvency, enabling the organization to be nimble in response to a crisis.

Implication 1: Notes Toward Articulating a Theory of Strategic Ambiguity in a Democratic Workplace

This study is a starting point toward articulating a theory of how strategic ambiguity may function in a democratically managed workplace. Though documents in a democratic organization may look like those created by a conventional organization, they may function quite differently. In the absence of a primary decision-maker or a hierarchical structure, regulatory texts act as a framework for the organization. Therefore, these jointly written governing texts balance ambiguity and precision. In such a unique workplace, ambiguity is not always benign and can either be debilitating or constructive. This study points to three factors that may play a critical role in determining whether ambiguity is destructive or constructive.

The individual vs. the collective

Successful use of strategic ambiguity may be determined by whether the language is prescribing action for the individual or the collective. Used to guide the collective, ambiguous documents like bylaws encouraged conversations and concerted action on behalf of the organization, fostering unity among diverse goals and motives. Used to guide individual behavior, however, ambiguity afforded for multiple interpretations which eventually led to unmet responsibilities.

Abstract vs. concrete

Another determinant of the successful use of ambiguity is whether the language is describing the abstract or the concrete. In documents that addressed abstractions like mission statement and values, i.e., those intended to guide decision-making, ambiguity was successful in allowing for flexibility and change. In documents that were intended to be concrete and actionable, e.g., those that measured whether an individual was following guidelines, ambiguity slid into dysfunction. Nevertheless, on a small scale, like Owen’s House when it first opened, some ambiguity in job descriptions may be desirable to allow for adaptation in a growing organization.

Scale

In a small organization (such as a start-up, small nonprofit, or community organization), flexible job descriptions may be a successful strategy. For example, in the case of the original descriptions at Owen’s House, people were engaged in weekly or even daily conversations about the shape of the business. Employees adjusted their roles according to changing organizational needs. However, as the organization grows, turn-over occurs, or communication breaks down, more specificity may be needed to ensure roles and responsibilities are consistently fulfilled.

Implication 2: Ambiguity in Regulatory Documents Challenges the Assumed Role of Clarity

Another consequence of this study is that it upends assumptions about clarity in documents that structure and regulate organizational behavior. That is, the calculated deployment of ambiguous language in regulatory documents tests the assumed requirement of clear and precise language, a nearly ubiquitous assumption in TPC education, practice, and research. A precisely worded and prescriptive document often requires a unanimous, solitary interpretation. Because it operates through consensus, this kind of unanimity may be difficult if not impossible to achieve in a democratically managed business. This kind of unanimity may be difficult to achieve in other types of organizations as well, especially during the nascent stage. Nevertheless, as in the case of Owen’s House, certain documentation must be created in order to be incorporated. A careful use of ambiguity could be a tactic for constructing the organization, if only temporarily. Still, this tension between the need for consensus and the need for regulatory documents requires more research, especially within the context of alternative organizations.

My project demonstrates that there is still much to learn about these organizations and the way they write and enact documentation. For instance, what TPC approaches could be useful for writing successful technical documents within these unique configurations of power? With the social justice turn in TPC scholarship (Agboka, 2013; Agboka, 2014; Colton & Holmes, 2016; Colton & Walton, 2015; Jones, 2016; Jones, Moore, & Walton, 2016), how can TPC scholars better understand and provide support to the important democratic work these kinds of organizations are doing? What can more traditional organizations learn from the way these firms write and implement documentation, and vice versa? Democratic firms may provide new terrain for exploring TPC in marginalized sites. These organizations may contest assumed TPC goals and values. Owen’s House challenges the ubiquitous value of clarity. Intentionally embedding ambiguity into documents may be a way for such flat organizations to strategically adapt to challenging situations and grow into successful businesses. In a democratic organization, though documents may look conventional, the processes through which they are created, used, and revised may be very different, and there may be much for us to learn.

References

Agboka, G. (2013). Participatory localization: A social justice approach to navigating Unenfranchised/disenfranchised cultural sites. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22, 28–49.

Agboka, G. (2014). Decolonial methodologies: Social justice perspectives in intercultural technical communication research. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 44, 297–327.

Alvesson, M. (1991). Organizational symbolism and ideology. Journal of Management Studies, 28(3), 207–226.

Berlin, J. (1988). Rhetoric and ideology in the writing class. College English, 50(5), 477–494.

Blyler, N. R. (1995). Research as ideology in professional communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 4, 285–313.

Clark, D. (2006). Rhetoric of empowerment: Genre, activity, and the distribution of Capital.” In Ed. M. Zachry and C. Thrall (Eds.), Communicative practices in workplaces and the professions: Cultural perspectives on the regulation of discourse and organizations (pp. 155–179). Amityville, NY: Baywood.

Cheney, G. (1995). Democracy in the workplace: Theory and practice from the perspective of communication. Journal of Applied Communication, 23, 167–200.

Colton, J., & Holmes, S. (Forthcoming). A social justice theory of active equality for technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication.

Colton, J. S., & Walton, R. (2015). Disability as insight into social justice pedagogy in technical communication. Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, 8. Retrieved from https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/disability-as-insight-into-social-justice-pedagogy-in-technical-communication/

Contractor, N. S., & Ehrlich, M. C. (1993). Strategic ambiguity in the birth of a loosely coupled organization: The case of a $50-million experiment. Management Communication Quarterly, 6(3), 251–281.

Craig, B., & Pencavel, J. (1995). Participation and productivity: A comparison of worker cooperatives and conventional firms in the plywood industry. Brookings Papers: Microeconomics, 121–174.

Davenport, S., & Leitch, S. (2005). Circuits of power in practice: Strategic ambiguity as delegation of authority. Organization Studies, 26(11), 1603–1623.

Devitt, A. J. (1991). Intertextuality in tax accounting: Generic, referential, and functional. In Charles Bazerman and James Paradis (Eds.), Textual dynamics of the professions (pp. 336–348). London, UK: Board of Regents of University of Wisconsin System.

Doheny-Farina, S. (1993). Research as rhetoric: Confronting the methodological and ethical problems of research on writing in nonacademic settings. In R. Spilka (Ed.) Writing in the workplace: New research perspectives, 253–267.

Eisenberg, E. M. (1984). Ambiguity as strategy in organizational communication. Communication Monographs, 51(3), 227–242.

Eisenberg, E. M. (1994). Dialogue as democratic discourse. In E. M. Eisenberg (Ed.) Strategic ambiguities: Essays on communication, organization, and identity (pp. 118–128). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Eisenberg, E. M. (2007) Strategic ambiguities: Essays on communication, organization, and identity. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Eisenberg, E. M., & Goodall, H. L. (2001). Organizational communication: Balancing creativity and constraint. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Eisenberg, E. M., & Witten, M. G. (1987). Reconsidering openness in organizational communication. Academy of Management Review, 12(3), 418–426.

Faber, B. D. (2002). Community action and organizational change: Image, narrative, identity. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Fakhfakh, F., Perotin, V., & Gago, M. (2009). Productivity, capital and labor in labor managed and conventional Firms. Document de travail Ermès.

Gee, J., Hull G., & Lankshear, C. (1996). The new work order: Behind the language of new capitalism. Sydney, Australia: Westview.

Gordon Nembhard, J. (2014). Collective courage: A history of African American cooperative economic thought and practice. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State UP.

Hale, H. E., et al. (8 September 2009). Russians and the Putin-Medvedev “Tandemocracy”: A Survey-Based Portrait of the 2007-08 Election Season. The National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, Seattle, University of Washington.

Hampton, C. (n.d.). Section 7. Writing bylaws. Community Tool Box. Retrieved from http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/structure/organizational-structure/write-bylaws/main

Harrison, T. (1994). Communication and interdependence in democratic organizations. Communication Yearbook, 17, 247–274.

Herndl, C. G. (1991). Writing ethnography: Representation, rhetoric, and institutional practices. College English, 53(3), 320–332.

Herndl, C. G. (1993). Teaching discourse and reproducing culture: A critique of research and pedagogy in professional and non-academic writing. College Composition and Communication, 44, 349–363.

Jarzabkowski, P., Sillince, J. A., & Shaw, D. (2010). Strategic ambiguity as a rhetorical resource for enabling multiple interests. Human Relations, 63(2), 219–248.

Johnson-Eilola, J. (1996). Relocating the value of work: Technical communication in a post-industrial age. Technical Communication Quarterly, 5, 245–270.

Jones, N. (2016). The technical communicator as advocate: Integrating a social justice approach in technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46, 342–361.

Jones, N., Moore, K., & Walton, R. (2016). Disrupting the past to disrupt the future: An antenarrative of technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 14, 211–229.

Kastelle, T. (2013). Hierarchy is overrated. Blog. Harvard Business Review. November 20. http://blogs.hbr.org/2013/11/hierarchy-is-overrated/

Keyton, J. (2005). Communication and organizational culture: A key to understanding work experiences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Longo, B. (2000). Spurious coin: A history of science, management, and technical writing. New York, NY: SUNY UP.

McNely, B., Spinuzzi, C., & Teston, C. (2015). Contemporary research methodologies in technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 24, 1–13.

Miller, C. R. (1984). Genre as social action. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 70, 151–167.

Paul, J., & Strbiak, C. A. (1997). The ethics of strategic ambiguity. Journal of Business Communication, 34, 149–159.

Pittman, L. (n.d.). Cooperatives in Wisconsin: The power of cooperative action. UW Center for Cooperatives.

Owen’s House Cooperative. [Name redacted] cooperative bylaws. Ratified March 2011.

Owen’s House Cooperative. (2013). [Name redacted] Board manual. Unpublished.

Owen’s House Cooperative. (2012). Introduction to [Name redacted] Workers Collective. Presentation.

Owen’s House Cooperative. (2012). Job Descriptions & division of labor for the [Name Redacted] Workers Collective; Introduction to Workers Collective.

Robertson, B. (2015). Holacracy: The new management system for a rapidly changing world. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Co.

Schryer, C. (1994). The lab vs. the clinic: Sites of competing genres. In A. Freedman and P. Medway (Eds.), Genre and the new rhetoric (pp. 104-124). London, UK: Taylor.

Spinuzzi, C. (2005). The methodology of participatory design. Technical Communication, 52, 163–174.

Spinuzzi, C. (2013). Topsight: A guide to studying, diagnosing, and fixing information flow in organizations. Austin, TX: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Spinuzzi, C. (2013). All edge: Understanding the new workplace networks. [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/spinuzzi/all-edge-understanding-the-new-workplace-networks

Spinuzzi, C. (2014). How nonemployee firms stage-manage ad-hoc collaboration: An activity theory analysis. Technical Communication Quarterly, 23, 88–114.

Spinuzzi, C. (2015). All edge: Inside the new workplace networks. Chicago, IL: UP.

The cooperative movement and the challenge of development: A search for alternative wealth creation and citizen vitality approaches in Uganda (Dec. 2013). Published by The Uhruru Institute.

Walton, R., Colton, J. S., Wheatley-Boxx, R., & Gurko, K. (2016). Social justice across the curriculum: Research-based course design. Programmatic Perspectives, 8(2), 119–141.

Walton, R., Mayes, R. E., & Haselkorn, M. (2016). Enacting humanitarian culture: How technical communication facilitates successful humanitarian work. Technical Communication, 63, 85–100.

Walton, R., Zraly, M., & Mugengana, J. P. (2015). Values and validity: Navigating messiness in a community-based research project in Rwanda. Technical Communication Quarterly, 24, 45–69.

Waterman, Jr., R. H. (1990). Adhocracy. New York, NY: Norton.

Williams, R. G. (2007). The cooperative movement: Globalization from below. Hampshire, UK: Ashgate.

Wilson, G. (2001). Technical communication and late capitalism: Considering a postmodern technical communication pedagogy. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 15, 72–99.

Winsor, D. A. (2003). Writing power: Communication in an engineering center. Albany, NY: SUNY

Winsor, D. A. (2007). Using texts to manage continuity and change in an activity center. In M. Zachry and C. Thrall (Eds.), Communicative practices in workplaces and the professions: Cultural perspectives on the regulation of discourse and organizations (pp. 3–20). Amityville, NY: Baywood.

Zachry, M. (2000). Communicative practices in the workplace: A historical examination of genre development. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 30, 57–79.

Zeuli, K. A., & Cropp, R. (2004). Cooperatives: Principles and practices in the 21st Century. University of Wisconsin Extension Publication A1457. University of Wisconsin Center for Cooperatives.

Zuboff, S. (1988). In the age of the smart machine: The future of work and power. New York, NY: Basic Books.

About the Author

Avery C. Edenfield is an assistant professor of Technical Communication and Rhetoric at Utah State University. His research agenda works at the intersections of professional communication and community-embedded workspaces with specific attention to cooperatives, collectives, and nonprofits. His research interests include theories of participation, rhetorics of empowerment and democracy, and community engagement in professional communication. Avery’s work has appeared in Journal of Technical Writing and Communication and Nonprofit Quarterly. He can be reached at avery.edenfield@usu.edu.

Manuscript received 19 January 2017, revised 30 April 2017; accepted 1 August 2017.