Benjamin Lauren and Joanna Schreiber

Abstract

Purpose: This article presents the results of an integrative literature review on project management in technical and professional communication. The goal of the article is to demonstrate how project management has been discussed and studied by the field. By analyzing the field’s approach to project management, the article sets groundwork for research, pedagogies, and best practices that prepare technical and professional communicators to shape effective project management practices.

Method: To achieve this goal, we assembled a sample of 326 sources across academic and practitioner publishing venues from the years 2005–2016. To comprise the sample, we used targeted keyword searches to identify published work that addressed project management in technical and professional communication.

Results: Project management in technical and professional communication is often presented as an adjacent practice to other concepts or practices, such as leadership or documentation management. Additionally, project management is described or discussed primarily in terms of skills and relationships established through concepts such as teaming, collaboration, professional communication, communication theory, and education.

Conclusion: The limited characterization of project management in the existing research creates the opportunity for technical and professional communicators (TPCs) to explicitly acknowledge the complexity of project management from a rhetorical perspective. The outcome of this rhetorical approach would position TPCs to develop and shape ethical and audience-focused PM practices through their communication expertise.

Keywords: project management, integrative literature review, rhetoric, technical and professional communication

Practitioner’s Takeaway:

- Project management links TPC tools and processes with organizational and team contexts.

- Project management skills are essential for developing and sustaining TPC careers, especially since teams are more often sharing in project management activities.

- Project management processes are often discussed as a skillset for TPCs to acquire rather than as a practice to be refined for different organizations, teams, and individuals.

- More methods in project management should emphasize the importance of effectively communicating with people to do complex knowledge work, an area of opportunity for TPCs.

- Acknowledging the complexity of PM as a field helps TPCs define the value of their work.

Technical and professional communication (TPC) has discussed project management (PM) for some time (Carliner, 2004; Carliner et al., 2014; Giammona, 2004; Lanier, 2009), and recent shifts in organizational structure, approaches to product development, process management, global economics, and team practices (see Hart & Conklin, 2006; Dubinsky, 2015; Spinuzzi, 2015) suggest it remains essential to the TPC skillset. Yet, published work on PM in TPC focuses almost entirely on practice—evaluating tools and describing processes and methods. This focus on practice has positioned PM as a skill to be acquired or developed (Dicks, 2010; 2013) rather than as a kind of knowledge used to shape how people work within and across organizations. Also, by positioning PM as just a needed skillset, TPC may be missing opportunities to critically evaluate emerging forms of PM, particularly how it informs the ways in which we work and what we produce. For a field and profession that takes great pains to explain writing as complex knowledge work (Allen,1990; Johnson, 1997; Miller, 1989; Winsor, 1999), the lack of critical engagement with PM seems almost out of character. Or, as Dicks (2013) put it, “For an area that is as critically important to technical communication as project management, it is surprising that there are not more articles in the literature dedicated to the subject” (pp. 311–312).

Given these observations on TPC work in PM, we believe the timing is appropriate for an integrative literature review of published work that brings together conversations about PM in our field. To be clear, an integrative literature review does not aim to integrate everything published about a topic in a given discipline; instead, it works to assemble “representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated” (Torraco, 2005, p. 356). In this article, we offer an integrative literature review of PM in TPC that draws from publications offered in both academic and practitioner venues.

But why is the time right for an integrative literature review on PM in TPC beyond what we’ve noted already? Many people who work in TPC note the field is undergoing disciplinary transformation, expanding the role and scope of our work. We briefly summarize some of these transformations in the following points:

- How technical and professional communicators (TPCs) are participating on project teams is and has been evolving. For example, Spinuzzi (2015) recently described how some teams share PM activities. On these teams, PM is not the job of a single person but an activity practiced and coordinated across a team, so TPCs must be prepared to participate in project management.

- TPCs have an important leadership role to play in the facilitation of cross-functional project work (Dubinsky, 2015; Hart & Conklin, 2006; Marchwinski & Mandziuk, 2002). Healthy communication workflows are intrinsic to effective teamwork, and TPC has important value in conversations about effective communications management (Amidon & Blythe, 2008; Suchan, 2006).

- Emerging development methodologies like Agile, Lean, Six Sigma, and so on (Hackos, 2016; Schreiber, 2017) have had an important influence on TPC practice. Understanding how these methodologies contribute to our work is key to establishing the value of TPC in leadership roles, particularly as information developers are given “autonomy to manage many day-to-day tasks” (Agile Development, para 6).

- Content management and strategy has changed who can participate in the development of content (McCarthy et al., 2011) and how technical and professional communicators organize work practices (Hart-Davidson et al., 2008). Additionally, tools and processes related to content management further shapes TPC field knowledge, organizational position, and role on teams.

These transformations, while certainly not exhaustive of every shift the field is experiencing, demonstrate the pervasiveness of PM in TPC. We believe these shifts also suggest it is a good moment to assemble and examine how TPC practitioners and academics are approaching PM so that we can critically reflect on how, as a field, TPC is contributing to the development of emerging PM practices and theories. Therefore, this integrative literature review seeks to 1) document emerging areas for PM research in TPC and 2) present a critique of existing work with the goal of identifying gaps and opportunities for future research and identification of best practices.

To provide some background, we begin the article with a brief history of PM scholarship in TPC. We continue by describing our methods for assembling the scholarship into a conversation. Next, we explain the results of our review, which demonstrates that PM is often discussed in relationship to other activities, such as leadership practices or teams and teaming. After reporting our results, we discuss implications of the findings and offer a critique of the scope of published work on PM. Finally, after discussing the limitations of our research design and results, we conclude the article with several suggestions for future study.

Brief history of PM

While documenting every event or factor that influenced the evolution of PM and PM in TPC is beyond the scope of this article, this section briefly gives key moments to show PM has historically developed in sometimes parallel and overlapping ways with TPC.

PM as a workplace practice emerged from efficiency management structures and efforts to organize work which took hold in the early 1900s (Miller, 1998). Additionally, PM grew out of engineering and science, specifically through advancements in knowledge and resulting complexities which surfaced due to product development and research (Longo, 2000). Advances in information communication technologies and flattened organizational structures required inventing methods to scale operations (Yates, 1989), so PM can also be traced across a trajectory of organizational development. Research has also traced TPC practices as foundational to the development and implementation of early scientific management work (Killingsworth & Jones, 1989), and it is these early efficiency practices which also marked the beginning of PM as part of organizational management structures.

World War II was an important touchpoint for both TPC and PM as scientific and technological products grew increasingly complex and dangerous, requiring documentation and interdisciplinary teams (see Morris, 2011). Later, in the 1960s, many of the PM processes and tools that were developed in the military became more widely adopted (for example, Program Evaluation Review Technique, or PERT), and were intimately tied to managing and improving team processes. By 1969, the Project Management Institute (PMI) was formed to act as a hub for professionals and helped standardize PM as a practice and discipline. Later, in the 1980s, white collar managers in the United States adopted Lean principles as a way to increase profits by doing more with less (Saval, 2014). At this time, interest in process improvement remained an important concern of management professionals and was dramatized in the popular business novel The Goal by Goldratt and Cox (2014). In product-focused environments, technical and professional communicators often developed end user documentation. Later, the first official Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) was released in 1996, which created opportunities for professional training and certification in PM.

In the 2000s, PM approaches became more closely aligned with software development methodologies, like Agile development. In 2001,The Agile Manifesto was published. At this time, commercial software development changed how projects were managed as teams moved from developing physical products for manufacturing to developing software. As well, documentation began to move from print to screen. Effective processes of developing and publishing documentation was captured by a range of texts, including Hackos’ (2007) Information Development (which is widely regarded as a foundational text for defining PM in the context of TPC). While more recent scholarship on coordinating work (see Pigg, 2014) certainly informs PM practices, Hackos’ (2007) work was the most recent substantial contribution to PM in TPC.

As this brief history shows, PM and TPC are increasingly connected and even merge at some points. Despite shared history, TPC often treats PM as an important practice to acquire or wrestles with best methods for teaching others how to do it. Although many have argued that TPCs would make for excellent project managers and facilitators of work (see Hart & Conklin, 2006; Potts, 2014), we also believe that our field has an important role to play in shaping PM as a social practice.

Method

As our introduction and brief history of PM shows, PM has been discussed as an important skill, particularly as TPC work and roles transformed. However, we ask a central question: What has TPC as a field more recently offered about PM knowledge? To answer this question, we used Toracco’s (2005) work to shape our analysis of published work, using elements of grounded theory (Charmez, 2006) to organize and locate emerging themes as we read each article in our sample. We captured articles broadly with a range of keywords and refined our sample with focused readings to determine which articles addressed PM. To further guide our analysis of PM in TPC, we asked three research questions:

- How is PM described as a practice?

- What communication theory is studied in the context of PM?

- What PM methods are being discussed?

Integrative literature reviews help to generate new knowledge about a topic studied because mature topics have more room for critique, whereas the goal for emerging areas is to simply capture the conversation. Torraco (2005) explained, “Most integrative literature reviews are intended to address two general kinds of topics–mature topics or new, emerging topics” (p. 357). Additionally, Torraco suggested mature topics and emerging topics have different goals in mind. Our research is specifically designed to study a relatively mature phenomenon (because we have accounts of PM in TPC) that has recently undergone shifts in disciplinary practice.

Sample

To start, we identified major publication venues and platforms in TPC. Since we were specifically interested in emerging accounts of PM in TPC, we identified the date range January 2005 to September 2016. To capture academic conversations, we focused on journals whose mission was technical communication, professional communication, or both. We identified journals central to technical and professional communication and those that directly overlap. To capture practitioner conversations, we included User Experience Magazine, TC World, and Intercom. Additionally, since both academics and practitioners publish proceedings papers, we searched two popular conferences: the International Professional Communication Conference (ProComm) and the Special Interest Group on the Design of Communication (SIGDOC). We also searched using Google, Google Scholar, and Amazon.com to identify major textbooks and edited collections. We defined edited collection broadly and included two special issues from International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development because they were edited by TPC scholar Guiseppe Getto and focused on user experience PM. To make sure we identified appropriate texts as we assembled the sample, we engaged in an ongoing dialogue about project scope as we searched. We included articles from the following journals/proceedings in our final sample:

- Technical Communication

- Journal of Business and Technical Communication

- Transactions on Professional Communication

- Technical Communication Quarterly

- Business Communication Quarterly

- Special Interest Group on the Design of Communication (SIGDOC) Proceedings

- Journal of Technical Writing and Communication

- International Professional Communication Conference (ProCommO Proceedings

Next, we searched abstracts, keyword lists, and/or metadata (if the database included such information) of articles in each publication for our time period. In order to broadly capture PM in TPC, we used the keywords “project management,” “management,” “project,” “teams,” “collaboration,” “Agile,” “Lean,” and “leadership.” We also included slight variations of these terms, such as “project manager,” “teamwork,” or “project leader.” To isolate project management and to make our sample manageable, we did not explicitly include phrases or terms that included “management,” such as “knowledge management,” “content management,” “information management,” “documentation management,” “crisis management,” “impression management,” or “boundary management” (some of which have already received their own integrative literature reviews; see Andersen & Batova, 2015). Since the goal of this project was to focus on PM specifically, we only selected articles for our sample that directly tied themselves to PM in a substantive way. From our initial searching, we assembled 326 potential sources after removing book reviews and other similar texts. To further narrow our sample, we evaluated each source to determine its relevance to PM, finding that 128 texts of our initial sample substantively discussed PM. Also, throughout the writing and revising process, we continued to review our sample through additional searching as previously described to make sure coverage was appropriate.

Iterative Coding Method

To evaluate our sample, we developed starter codes and piloted them on a small portion of the work to norm our approach. We drew from grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006) to develop an iterative and systematic process for refining our codes and analyzing our sample, giving “priority to showing patterns and connections rather than linear reasoning” (p. 126). For instance, in testing our original codes, we discovered that methods and tools were often interchangeably used, and that, to capture how PM was defined, we needed to code more broadly to capture both direct definitions of PM and definitions of PM that were focused on solving particular problems. This approach helped us focus on relationships and linkages between PM and several areas of interest to TPC, and our coding scheme was useful in discovering other broad TPC knowledges and practices. Table 1 demonstrates how we revised our starter codes. As well with our sample, we regularly reviewed our codes throughout the coding process.

Themes

After reading through the sample, we assembled the findings by emergent themes produced by each reading. We moved summaries of the texts into a document and developed themes through an iterative process of analysis and reanalysis (Charmez, 2006). Once initial themes were created, we continued to reevaluate relationships between the themes to collapse our summaries into more specific categories, using our research questions as broad organizational categories for the themes. For example, we found a small number of articles about technology as they related to PM (as opposed to technology used to facilitate PM) and space as relates to PM; we combined these articles into a theme about environmental factors that influence PM. Our findings are more fully detailed in the next section of the article.

Results

We organized our results according to 1) a quantitative breakdown of the sample; 2) emerging themes; and, 3) how the results addressed our research questions.

Sample Breakdown

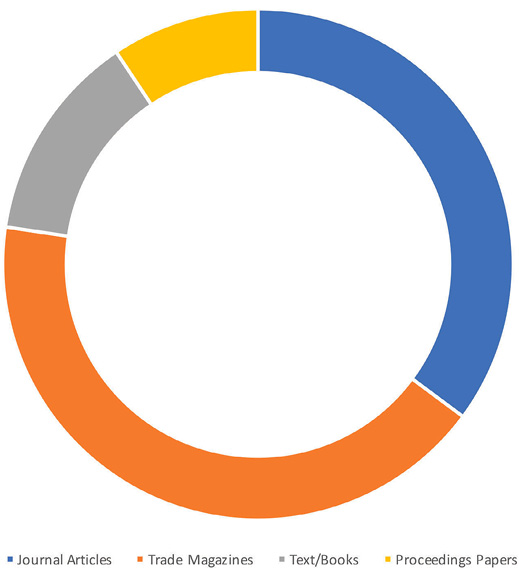

Examining the breakdown of our sample reveals some useful insight. Figure 1 demonstrates the overall breakdown of genres included in the sample. The largest category of our sample was trade magazines (Intercom, TC World, and User Experience Magazine). The second largest was journal articles, followed by textbooks, academic monographs, special issues, and classroom/instructional texts. Lastly, proceedings papers (SIGDOC) made up the smallest amount of our sample. Often, the published cases focused a great deal on describing practice or offering advice, echoing the sentiments of Dicks (2013) that much of the published work on PM in TPC over the last ten years has been largely descriptive and/or prescriptive.

Additionally, PM was rarely the primary topic in our sample, though many texts established links between PM and other workplace activities and experiences. Once again drawing from Charmez (2006), we identified this quality as “relationships.” As a point of order, we organized the results by aligning them with the corresponding research question. We also would like to note, due to space constraints, we did not discuss each article from the sample in detail.

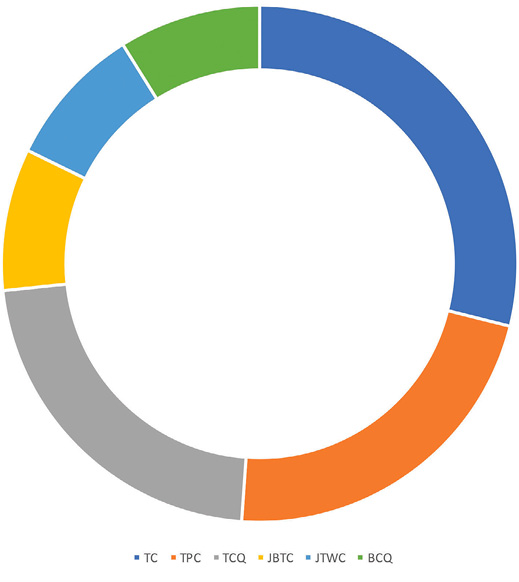

Below, Figure 2 demonstrates the breakdown of our sample by academic publishing venue. The largest sample was from Technical Communication (TC), followed closely by both Technical Communication Quarterly (TCQ) and Transactions on Professional Communication (TPC). The topic of articles published in these venues varied, but there was considerable interest in describing and teaching current PM practice to students. Coincidentally, the sample size was similar across the Journal of Business and Technical Communication (JBTC), the Journal of Technical Writing and Communication (JTWC), and Business Communication Quarterly (BCQ). As with the other journals, the topic range of articles in JBTC, JTWC, and BCQ varied. The abbreviations used here are the same in Figure 2.

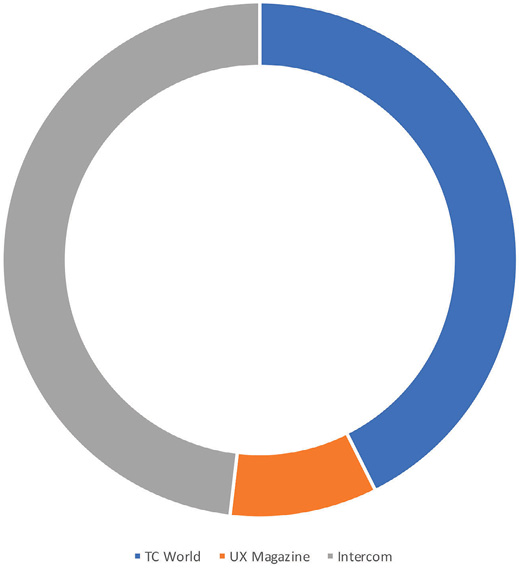

Figure 3 illustrates the trade magazines included in the final sample. We discovered that trade magazines appeared to have most interest in demonstrating the practice of PM in different organizational circumstances. As the majority of our sample (by just 7%), the articles published in trade magazines were instructive and useful for professionals interested in developing individual careers. Additionally, it appeared there was a similar focus on PM across both TPC World and Intercom. User Experience Magazine, or UX Magazine, discussed PM in the context of user experience, which overlaps with TPC. During our reading, we noted some redundancy across the topics and experiences detailed in trade articles.

Table 1. Revised code categories after pilot

| Code | Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Identity/Role of Project Manager on Team | #ID | The power relationships expressed between leadership and team (or lack thereof) and/or purpose of the leader (?) |

| TPC Problem or Question | #TPCprob | What is the TPC research question or problem/issue the author is trying to address? |

| Communication Theory and Method | #CTM | How a communication theory is chosen and applied |

| Implementation Methods & Tools | #IM | The project management methodology and the methods in support of it.

For example, management philosophies and related tools/frameworks. Can be lean (philosophy/method) and tool (agile) or lean (philosophy/method) and tool (kaizen) or agile (philosophy/method) and tool (scrum) |

Emerging Themes

Because few articles in our sample focused only on PM in TPC, the emerging themes we discovered describe relationships between related concepts and practices and PM. While we believe there is much to be gained from the results of our literature review, we wish to highlight two overarching themes:

- PM is often presented as an adjacent practice to other concepts or practices (for example, leadership or documentation management), instead of grounding these practices together theoretically (for example, providing a framework for related concepts like collaboration, leadership, interpersonal communication, and user experience) and contextually (for example, foregrounding relationships between several related workplace practices and structures like information management and management philosophies).

- PM is described or discussed primarily in terms of skills (for example, as a necessary skill or as something requiring particular skills) and relationships (for example, how it relates to teams, collaboration, professional communication, communication theory, and education).

PM’s relationship to leadership and management

Our findings show PM was often positioned in conversations related to leadership and management, and that these terms were often conflated. For example, in a study by Flammia, Cleary, and Slattery (2010), “team leaders” were responsible for PM activities on distributed teams of students. In their study, students from the University of Central Florida and the University of Limerick were paired on a Web development project with team leaders who are described as “those individuals who took the initiative to establish communication and to keep teammates on task” (p. 94). Additionally, “team leaders” tended to take responsibility for activities typically assigned to project managers. Walton (2013) examined how trust and credibility influenced development projects, defining the PMs as “project leaders, who envisioned the project from the beginning and spearheaded the early, exploratory research efforts” (p. 90). While reflecting on experiences managing projects with globally distributed teams, Aschwanden (2013) also addressed leadership in terms of shared approaches to managing projects and gives examples of how roles are negotiated by teams. He noted that one way to create familiarity with each other is to create opportunities to for teams to meet face-to-face.

Several authors argue that TPCs are well positioned for leadership roles. For instance, Sturz (2012) discussed the outcome of when TPCs are also information and knowledge-managers, suggesting they are participating in management activities. In integrating these activities,

Does the technical writer then bear the responsibility for everything in the organization? No, but management of information, knowledge, and communication and certainly even other areas of process management, insofar as they entail dealing with information, should be in the focus of technical writers not just within the documentation department, but also across the company. (Sturz, 2012, n.p.)

The call for leadership is echoed by practitioners and academics alike. For example, Potts (2014) argued TPCs should be in leadership positions on teams. Similarly, Gosset (2012) made an argument suggesting that TPCs have the skills to manage projects “across industries” (n.p).

When discussing leadership and PM, scholarship has also focused on describing roles and responsibilities. The role of leader and the role of project manager may or may not be fulfilled by the same person (Tebeaux & Dragga, 2015; Wolfe, 2010). Wolfe (2010) argued that the PM should not be confused with the leader or boss: “Instead of viewing the project manager as some kind of supervisor, think of the project manager as someone who plays a specific role on the team by keeping the project on course” (p. 13). Tebeaux and Dragga (2015) described collaborative projects as having a leader, but the leader may or may not actually be the PM. Further illustrating this dynamic, Vang (2016) explained, “Writers serve not just as resources on project teams but also as leaders within those teams. The lead or sole writer on a project is often responsible for planning and managing relevant tasks within that project” (p. 21). The overlap between managing, leading, and writing often seemed part of how unique workplaces would position writers to manage and lead their own project work.

As with the concept of leadership, management and PM could also be conflated concepts. Nevertheless, PM is also described as a skill appreciated by upper management. Studies of TPC managers conducted in the last decade have cited PM as a desirable skill for TPCs (Amidon & Blythe, 2008; Rainey, Turner, & Dayton, 2005). Baehr (2015) cited PM as a skill TPCs find important and as a role TPCs take on as they move through an organization. As well, Kimball (2015) explained PM as something useful to learn as part of TPC education. Management was also discussed as a changing structure that affects the need for PM. Dicks (2010) argued that changes in management structures and fads are as important for TPCs to pay attention to as well as changes in technology. Flattening team and organization structures require TPCs to be better able to explain value and to work autonomously—thus the need for PM skills. Because communication skills are so central to the success of TPCs, Lewis (2012) argued projects and working with PMs are opportunities to illustrate TPC value.

Finally, it is worth noting some emerging interest in PM, leadership, and gaming. The terms of management, leadership, and PM appeared conflated in this scholarship as well. Two examples, in particular, seemed relevant because of the emphasis on managing communities of people. Robinson (2016) studied World of Warcraft ad-hoc teams in virtual worlds to understand which leadership traits were most valuable, concluding: “Managers of virtual teams might also reconsider the ways in which they assign or talk about leadership; allowing teams to utilize emergent leadership might yield better performance” (p. 188). Meanwhile, McDaniel and Fanfarelli (2015) explored the concept of micro-project management in game design. Their interest was specifically focused on how user experience principles can be used to help manage game development.

PM’s relationship to teams and teaming

PM was sometimes discussed in scholarship that focused on managing globally distributed teams. It was also referenced in scholarship that addressed collaboration as an activity and in other work focused on forming team dynamics.

The global marketplace has influenced many workplaces that TPCs encounter, particularly as they work on the development of products and services. As a result, TPC scholarship has been interested in globally distributed and virtual teams for quite a while now. Weimann et al. (2013) report on an extensive case study that took place over two years and focused on 15 different virtual project teams. In their research, they found the importance of building and maintaining trust to ensure there is adequate infrastructure in place to access useful and appropriate information communication technologies and to make sure people benefited from their participation on the team (p. 348). The emphasis on infrastructure, communication, and participation on the team directly concerned PM. Others also argued the importance of building infrastructure for global teams so that they can function effectively (Marghitu & van der Zalm, 2007), the importance of people and ingroup relationships (Burian, 2013; Fox, 2015; Plotnick, Hiltz, & Privman, 2016), effective approaches to communicating in international environments (Wellings, 2009), and the importance of knowledge management for globally distributed teams, especially to guide the use of technology to support communication and information (Ramamurthy, 2009).

Another relationship presented itself in published work that focused on time management, teamwork, collaboration, and team dynamics. For example, Lanier (2009) defined PM skills as those based on collaboration, interpersonal communication, and multitasking. Mogull (2014) reported on a class project where students appeared to define some PM skills as “professional skills” like “teamwork” and “time management” (p. 354). Randazzo (2012) also explained a classroom project where students described PM as related to personal organization, but, over the course of the project, they also learned to define PM as having an “element of stamina” (p. 386). We can surmise Mogull’s (2014) and Randazzo’s (2012) findings build on Conklin’s (2007) work that argued PM skills are increasingly important for TPCs as they worked on cross-functional teams and also locate similar arguments offered by the Technical Communication Body of Knowledge (see the entry on Agile, in particular). Spinuzzi’s (2015) work also emphasized the importance of having a PM skillset, describing workplace conditions that are networked and made up of contingent teams that share in project management activities.

Additionally, published work has discussed social norms, communication patterns, and communities of practice (Bartell & Brown, 2009; Fisher & Bennion, 2006; Vitas, 2013) and managing team conflict (Rose & Tenenberg, 2015), areas that directly influence how PM is practiced. Other authors discussed managing relationships between silos once a project has been developed (Kumar & Salzer, 2011) and different methods of collaborating on teams (Wolfe, 2010). Lloyd and Simpson (2005) illustrate a case study that explains the role of a PM as managing strands of “activity” (activities constituted prototype development, computer science research, clinical research, and blueprint development). Each of these areas may inform PM practice considerably, even though a feature of the research is it is context-specific.

PM’s relationship to specific kinds of workplace projects

We found intersections with documentation management, user experience, localization, and terminology management in the literature.

Hackos’ (2007) work provided a foundation for thinking about managing documentation projects, especially the influence of Agile on creating documentation. Additional accounts by both scholars and practitioners offer advice and resources for new documentation managers (Huettner, 2006), although some cover Scrum as a documentation management technique (Friedl & Worth, 2011), authoring platforms and their influence on managing documentation projects (Sabane, 2012), and the importance of planning for the unexpected in documentation projects (Brüggemann & Rehberg, 2014). Mara and Jorgenson (2015) discuss heuristics for managing UX projects. Additionally, Hart-Davidson (2015) discusses the role of UX as essential to the shift of “learning organizations,” which has implications for PM through activities like process improvement.

There also appears to be an interest in the role of PM in healthcare contexts. For example, Willerton (2008) illustrated a case about how online content about health is developed. He described project management as a cognitive process essential to the work of the team he studied for the case, noting the importance of timelines and managing individual information development activities. Similarly, Tomlin (2008) examined how the role of medical writers had changed given the availability of online regulations from the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In essence, the article suggested that the position of writers had become more central to development processes. The article concluded by arguing future curriculum should prepare medical writers to develop project documentation and take the lead on PM when applicable.

We also noted a relationship between PM and managing localization and translation projects, including managing terminology. The scholarship in this area appeared to originate in practitioner work. Several articles addressed managing localization and translation projects. Although not explicitly discussing PM as an isolated practice, Zerfaß and Schildhauer (2009) explained the importance of frameworks for information on localization projects, especially around four areas: “the project as a process; communications; tools and technologies used before, during and after translation/localization; and quality assurance” (para. 7). Others have written about running in-house translation departments (Salisbury, 2010), establishing essential tasks for teams to successfully navigate localization projects (Brown-Hoekstra, 2011), discussing the overlap of documentation and translation processes (Brown-Hoekstra, 2010), and, somewhat relatedly, creating healthy translation/localization departments and organizations (Yeng, 2013). Finally, Schmitz (2013) discusses the role TPCs sometimes take on when managing terminology to facilitate knowledge-transfer.

There was also some work that pointed to PM as organizational practice. For instance, Holdaway, Rauch, and Flink (2009) described how information designers can adapt to PM at all levels of organizations, specifically to deliver “excellence” or quality documentation as companies inevitably change management approach and style. Lastly, Condone (2008) explained that traditional forms of PM need to be augmented to manage multimedia projects effectively. The article assembled a list of best practices for managing unpredictable multimedia projects, such as “Know your project,” “Know your team,” and “Know your organizational structure under which you and your team fall” (n.p.). Mochal (2014) described project rescue as a particular project type that often gets overlooked but still needs to be approached systematically like other projects.

PM, teaching, and training

Many of the articles and books in the sample were intended for instructional purposes. We also found several articles about pedagogical approaches related to PM, particularly as they relate to on-the-job reference materials and service learning.

We identified instructional texts that focused on publication management for TPC managers. For example, Schwarzman’s (2011) book is specifically written for technical publication managers. Hackos’ Information Management (2007) provides guidance for documentation and information management projects, and remains a foundational text in this area. Kampf (2012) contributed a chapter in a text on engineering project management that focuses on teaching students to write effective project documentation. Though it is not specific to TPC, the PMBOK offers certification through the Project Management Institute and forwards concepts, such as the project lifecycle, that are meant to be a guide for PMs in most organizational contexts.

Additional texts focused on PM as important for collaboration and teams or using PM methods as pedagogical tools. Campbell (2007) argued the classroom was the place to develop team dynamics and learn to manage team projects. Kampf (2006) advocated for a rhetorical approach to teaching PM to prepare students to work on project teams. Ding and Ding (2008) argue that pedagogy must focus on developing socially responsible, critical reflective practice in teamwork, suggesting that PM methods can be incorporated to help manage these team projects. Lam (2015) builds on Ding and Ding (2008) and Wolfe (2010) by suggesting student teams develop communication charters as a way to help them avoid social loafing during group projects. As well, Smith (2012) devoted much of his PM textbook to teamwork and argued for “a set of heuristics for participating in and managing multidisciplinary teams” (p. 177). Kampf and Longo (2009) described a case study of students working to manage projects in global contexts, discovering that knowledge management and communication can productively influence project documentation. There was also a focus on learning from real-life case studies (Pflugfelder, 2016) as important for effectively teaching PM skills.

Other pedagogical approaches focused on teaching PM in the context of user experience (UX), an area that overlaps with TPC and has a rich history in the work of scholars like Pat Sullivan, Robert Johnson, and Jan Spyridakis. For example, Getto (2015) developed a set of heuristics for teaching PM in UX. Lund (2011) also offered a focus on managing UX teams, covering topics such as hiring people and evangelizing the team’s work. Among other areas of interest, the book advances discussions related to workspaces, explaining, “one of the things I have learned is that the physical environment you create can go a long way in shaping a team identity and climate” (p. 105). It is impossible to summarize all of the important ideas Lund forwards, but much of the advice blurs the line between management and PM (Lund recommends establishing communication plans for teams, which is traditionally a PM activity).

Ethics and rhetoric are noted as related to PM in multiple pedagogical articles. In these texts, rhetoric should be understood as audience-focused strategies for effectively and ethically communicating. For example, Hamilton (2009) offered a discussion on the ethics of managers motivating teams, noting several de-motivators in the process: “not listening,” “being inflexible,” “imposing arbitrary schedules,” “taking away power,” “withholding information,” “disrespecting people,” “not leading,” “personnel craziness,” and “market realities” (pp. 59-60). Textbooks (such as Rude and Eaton, 2011) build on the concepts in rhetoric that are widely taught in TPC college courses, such as audience and purpose. Rude and Eaton (2011) specifically lean on rhetoric to introduce PM as an important TPC skill in later chapters of their book.

PM methods have also been utilized as pedagogical tools. Rebecca Pope-Ruark’s (2014, 2015) work focuses on using Agile methods to teach professional writing and learn more complex rhetorical concepts. In these texts, rhetoric is used to help teach TPCs how to be more effective communicators. Agile has also been used to teach other skills, such as managing internships (Vakaloudis and Anagnostopoulos, 2015). Another example is offered by Beale (2016), who advocates teaching Agile methods using board games.

Research Question 1: How Is PM Described as a Practice?

How PM is described as a practice is addressed in two ways. The first and most prevalent way is to describe PM in terms of the skills and tasks required in the activity or PM as a needed skill in the workplace or as part of a necessary TPC skillset. The second is to describe how external or physical forces (documentation, technology, workplace design) appeared to influence or define PM practice in TPC.

PM in terms of skills or tasks

PM is described in the literature in terms of required soft skills for PM activity (Lanier, 2009; Michaels, 2005), organizational skills (Kimball & Hawkins, 2007; Lannon, 2008; Markel, 2015; Wolfe, 2010), and as a skill needed by TPCs (Carliner, 2012). Soft skills cited are collaboration, interpersonal communication, flexibility, multitasking, and communication skills (Green & DiGiammarino, 2014; Lanier, 2009; Michaels, 2005; O’Connor, 2006). Markel (2015) described PM as breaking down a project into “manageable chunks” and Lannon (2008) described PM as organizational strategies for keeping projects on track (goal setting, timetables, and setting meetings). Wolfe (2010) highlighted the PM’s role in task analysis and meeting minutes. Hackos (2007) specifically discussed implementing a new CMS and explained the PM’s role as keeping projects and tasks moving while other larger projects are being implemented.

Our sample also indicated it is important for PM practice to utilize the roles of peers effectively and to understand the value of their roles and associated knowledge. Lebson (2012) explained, “The project management triangle has three constraints: time, cost, and scope. It is important for the project manager and those on the project to understand how usability relates to these three constraints” (p. 13). Ames and Riley (2013) argued that it is very important that PMs and information architects understand the strengths the other brings to the table, because the success of the projects is reliant on these two roles utilizing each other’s skills effectively. Similarly, Berggreen and Kampf (2015) explored how technical documentation for projects can be developed through social and interpersonal interactions.

Interestingly, Green and DiGiammarino (2014) argue that the interpersonal skills necessary for PMs (the ability to negotiate and resolve conflict) are separate from the skills required for TPC work. This aligns with Herman’s (2013) contention that TPCs are in great positions to be PMs, but they need more than communication skills to successfully budget and scope projects as well as identify risks: “Project management is about leadership, team building, motivation, communication, negotiation, conflict management, political and cultural awareness, trust building, coaching, and decision making” (p. 7). One way to approach these skills is through modeling. Dyer (2012) argued that information architects (IA) benefit from modeling: “Models help IAs capture the benefit of a scientific process while leaving room for the art that happens when you innovate on the user’s behalf” (p. 19). Hackos (2012) also advocated the importance of mutual understanding between IAs and PMs as well as those roles’ understanding of writers’ work and value. Finally, Harris (2014) argued for developing skill maps in the workplace; he identified leadership and project management as two categories of skills/capabilities, with PM at their intersection. The skillset of the PM in this configuration seemed to focus on facilitation.

Discussions about the skills or tasks of PM also extended from producing documentation to highlighting rhetorical practices. PM has been described exclusively in terms of documentation or managing documents (see Rude & Eaton, 2011). As noted several times in the literature, PM has also been cited as a needed skill for TPCs, but some argue it is still not getting enough attention. For example, Henning and Bemer (2016) argued the Occupational Outlook Handbook entry for technical writing should be updated to include several skills, including PM. Importantly, PM skills have been explicitly tied to rhetoric. Berggreen and Kampf (2016) explored relationships between technical communication and stage-gate project management processes, concluding, “Project Management, and particularly the Stage Gate processes involved in project conception represent an area that is suited to the same types of rhetorical analysis used in designing communication” (n.p.). While the concept of rhetoric seemed most often aligned with work published in academic venues, it is still notable that rhetoric was the communication theory most often paired with PM.

PM and workplace contexts

Published work also discussed the environmental or physical factors affecting project management, such as TPC documentation (Walton et al., 2016), technology (Carliner, Qayyum, & Sanchez-Lozano, 2014; Dicks, 2010), and the design of the workplace (Lauren, 2015). Rather than focus on projects involving developing documentation, Walton et al. (2016) went a step further to highlight documentation as defining projects. Dicks (2010) argued that changes in technology alongside changes in management and organizational practices (for example, flattening structures) changed the way TPCs do their work—content oriented, single-sourcing—and thus influence PM practices and make them more important for TPCs. Carliner (2012) also argued that TPC work is influenced by business models, and the technologies used to facilitate PM are also an important factor. As such, TPCs need to understand how work can be tracked by PM systems, because these systems can be used to define value and productivity (Carliner, Qayyum, & Sanchez-Lozano, 2014).

Research Question 2: What Communication Theory Is Studied in the Context of PM?

Our findings indicate that PM is most often discussed through rhetorical frameworks used to evaluate and shape project communication. For example, Brizee (2008) writes about stasis theory, a rhetorical strategy, to help address the changing dynamics between subject matter experts and technical communicators in the workplace and the changing nature of collaboration practices. He argued, “We need to emphasize for our students and for our work teams the importance and value of using rhetoric for productive ends” (Brizee, 2008, p. 376). Others have discussed the importance of a strategic framework for managing change. For example, Bialek (2008) noted the importance of a communication plan for managing corporate culture change. She explained, “According to Marks and Mirvis, the following aspects are necessary to manage the merger syndrome: Insight, Information, Involvement and Inspiration. Communication is an essential part of all of those” (n.p.). Such communication frameworks seem an essential part of PM practice. Suchan (2006) also offered a change management plan that focused on designing effective communication by emphasizing the importance of dialogue.

In addition to rhetorical theory, intercultural communication has been discussed in the context of PM. For example, Ray, Reilly, and Tirrell (2015) argued the importance of intercultural communication in managing a distributed international grant project. Their work demonstrates the challenges of communicating and collaborating across distributed teams. Additionally, Happ (2014) discussed the importance of adjusting management and communication strategies when collaborating with people from different cultural backgrounds. To do so, she grounds her discussion in Chinese contexts and draws from existing cultural identity heuristics to guide the ideas. Corroborating this approach, Voss and Flammia (2007) advocated for a rhetorical approach to intercultural communication for teamwork, arguing, “Effective teamwork across multi-national business units adds an important new tool to the technical communicator’s skill set—intercultural sensitivity and rhetorical awareness (both verbal and nonverbal)” (p. 77). Certainly, the emphasis on ethical intercultural communication extends to the PMs leading these teams.

Research Question 3: What PM Methods Are Being Discussed?

In comparison to communication theories, implementation strategies were discussed less often in the sample. Of the existing strategies, Agile was discussed most frequently. This is not surprising. As Dicks (2013) stated: “Practitioners now refer to any method that seeks to abandon the waterfall method and use more streamlines processes as ‘agile,’ whether they happen to align with the ‘official’ agile methods espoused by the Agile Alliance or not” (p. 135). Though Agile or SCRUM (an Agile tool) are discussed as examples of preferred PM methods in the literature (Baca, 2014), some have argued that they require some getting used to (Sigman, 2007). Others have discussed Agile environments as opportunities for TPCs to expand their roles (Austin, 2014) or become embedded in teams (Smith & Gale, 2014). Collins (2014) recommended aligning existing documentation approaches with Agile methodologies. Moving beyond aligning existing approaches, Baker (2014) advocated for creating Agile TPC processes because it aligned with user content needs, explaining that Agile “requires us to create content as small, highly cohesive units that are loosely coupled. Happily, that is exactly the sort of content that works best for the new ways people seek and use content” (p. 27). Agile has also been promoted as a preferred method for conducting TPC practices relating to editing (Rude & Eaton, 2011).

As workflows shift and production cycles shorten, PM methods have moved away from the traditional step-by-step waterfall approach and toward more flexible, iterative strategies. Kimball and Hawkins (2008) offer iterative and mixed methods in addition to waterfall. Arguing that the traditional waterfall method can be “inefficient,” Dicks (2010, 2013) covered user-centered design (UCD), Agile, iterative, extreme programming PM methods. He also discussed SCRUM as a separate PM method from Agile. Both the Technical Communication Body of Knowledge (TC-BOK) and the PMBOK discuss Agile as influencing PM. The TC-BOK specifically addressed Agile as it influences the work of TPCs.

Discussion

Across the publication venues we reviewed, PM was generally positioned as a significant and important practice to TPC that requires training and education. Our literature review also showed that many of the accounts of PM in TPC seek to describe it as a prescriptive skillset that must be learned rather than as a workplace practice that requires critical attention and reflection. While we can point to examples in TPC that approach PM in organizations from a critical mindset (Hart-Davidson, 2015), as well as teaching cases that emphasize reflection through practice (Randazzo, 2016), this work seemed to be an exception. While we do not want to dismiss the importance of work that describes PM skills, we also believe that a better balance could be struck that asks deeper questions about how TPC can add to conversations about PM as a practice in meaningful ways. Below we make suggestions for several potential areas that research and practice might address:

Study and Practice of Implementation Methods

We see a strong opportunity for understanding how implementation methods like Agile, Scrum, and Lean influence the ways in which teams communicate and work with each other to manage projects and connect with customers. How do these methods shape what TPCs produce? How do they shape teams? Many teams trying out emerging implementation strategies are flatter in terms of hierarchy, and so, it follows that the communication strategies, practices, and philosophies being used may be responding to, rather than shaping, these new ways of working. Future research in this area might also examine how issues of power function on these flatter teams and how these circumstances influence the ways in which projects are managed and by whom.

We also think it would be useful to further investigate how inclusive implementation strategies are in practice. In TPC there are applications of implementation methods used to support teaching and learning (Pope-Ruark, 2012), but we might also stop to ask if these strategies are actually inclusive and equitable in practice. And, as we adapt TPC work to implementation methods like Agile (as described in the TC-BOK), we might ask if these methods of managing people and projects are producing ethical outcomes. Could TPCs be involved with making implementation strategies more ethical and inclusive? How do we support and instruct TPCs to anticipate rather than react to and adopt changing PM practices?

Conflation of Terminology

A second area we believe would be useful is a deeper analysis and understanding of the conflation of terminology we discovered. That is, PM, leadership, and management were often used interchangeably. We do not want to suggest that blurring terms is essentially an unproductive approach, but these ideas do presently serve very different functions in a variety of organizations. Research that aims at this issue might begin by asking about the roles of leadership, management, and PM—what distinguishes these ideas from each other and where are they purposefully being blurred for practical reasons? How do the terms being used to describe PM influence how people do the job? We think empirical research and reflective practice in this area, as well as a historical perspective in this area, would be productive.

Content Strategy and PM

One surprising finding was that little scholarship on Content Strategy (CS) directly addressed PM in our sample. In recent years, CS has appeared to replace discussions of publication management in TPC work. As Andersen and Batova (2016) explained, “Component content management—an interdisciplinary area of practice that focuses on creating and managing information as small components rather than documents—has brought significant changes to professional and technical communication work since 2008” (p. 2). The move away from developing documents toward managing content can be understood as embracing a model for TPC that focuses on integration. Andersen (2014) explained the shift as “integration of organizational and user generated content, disciplines and departments, expertise and roles, and business processes and tools” (p. 10). Such integration requires skills in PM, “but, as is too often the case, most technical communicators have not been trained to think like managers, business analysts, or content engineers” (p. 13).

In our view, CS is an important area of study that has already garnered a great deal of attention across academic and industry publication venues, but our research suggests its relationship to PM requires further analysis and understanding. For example, we might ask questions like, Is CS a kind of PM? What is the value of explicitly acknowledging the relationship between CS and PM? Have these two areas matured as separate but related practices? If so, how do they work or fit together? It seems there are implications from such questions that could affect the teaching, practice, and research of both PM and CS.

Teaching and Learning PM

Since TPC is very interested in educating students with a PM skillset, we believe further understanding of what comprises that skillset in today’s fast-paced, global workplaces, economies, and networks would be useful. Our literature review pointed out accounts of PM, for example, in health care, game development, and in cross-functional development teams. So, how do the variety of contexts where PM is practiced in TPC influence classroom curriculum, training materials, and, relatedly, the TC-BOK? Future instructional cases could look to assemble rhetorical frameworks for thinking about PM as more than planning, scoping, budgeting, and time-keeping. While we concede PM is made up of technical activities at times, it is also a social activity that requires audience-focused communication skills. Future instructional work might more specifically examine how we can prepare PMs to respond to the dynamics of their organizations, teams, and individuals.

Limitations

As with any study, our literature review has important limitations. The first limitation is the scope of the project. We did not include publications such as blogs, podcasts, or slide decks in our review. For the purposes of this research, we decided to focus on texts that had been published about or with inferred relationships to PM by venues that are widely recognized by the field. Although we do believe an expanded version of our literature review might consider such publication outlets, that was not the stated purpose of our article. As well, we chose not to pursue questions only about information communication technologies (ICTs) and their relationship to PM. Although there is some discussion of ICTs in areas of the review, the research produced on the role ICTs in PM we found useful as embedded into each section of our findings rather than as a separate section. It is possible, in hindsight, that a clearer relationship between CS and PM might have been established had we focused more on these relationships.

Other recent integrative literature reviews (see Andersen & Batova, 2015) explicitly studied the relationship between practitioner publication and scholarly publication approaches to their topic. We included both types of publications, but making direct comparisons was also not a stated goal of our research. Rather, we aimed to bring academic and practitioner publications into conversation without identifying the background of the text’s authors. As a result, we recognize additional practitioner publications and blogs as well as relevant scholarship from other fields (for example, management studies, sociology, and engineering) would enrich our findings, but we also argue these publications were beyond the scope of this particular project. Another literature review on PM might work to more deliberately assemble data from publication venues listed in the TC-BOK or from outlets such as Nielsen Norman Group or A List Apart.

Finally, while we worked to be exhaustive in this research, our scope created several other research design limitations. For example, at times by containing the scope of the project, we were forced to discover workarounds for the methods used by different databases to catalog publications (for example, the differences in the way one outlet uses keywords and metadata in comparison to another). We addressed these issues in dialogue with each other and responded to such issues as they surfaced—always in the spirit of assembling the most complete sample we could, given our study parameters. This approach led to us making judgment calls regarding published work we knew existed but could not include, because it was not published in one of the journals we identified or not within the years we specifically outlined for our sample. For example, Rebecca Pope-Ruark’s (2012) article “We Scrum Every Day: Using Scrum Project Management Framework for Group Projects” was published in College Teaching. To respond to such issues, we worked to include some sources in the introduction, literature review, and discussion sections to make sure they surfaced in our conversation in a meaningful way.

Conclusion: Toward a Rhetorical Approach to Developing PM Best Practices

Our integrative literature review shows that the literature from both academic and practitioner outlets discusses PM as primarily an adjacent practice to teamwork and collaboration or as requiring skills like leadership. At the same time, the literature demonstrated how often TPC published work collapses important areas like management and PM, even though these areas are rapidly changing alongside organizational structures and working practices. Thinking of PM not as simply relating to all of these things but actually situating them is important moving forward for TPC to develop flexible and sustainable best practices.

We believe a productive way to critically engage the complexity of PM is to rhetorically situate practices contextually (Andersen, 2014; Porter, 2010; Salvo, 2004). While TPC seems to be approaching the teaching of PM rhetorically, we also need to explicitly theorize the practices of PM rhetorically in the organizations where we work. By rhetorically situating, we mean that rhetoric theory offers TPCs the tools to critically analyze and align relationships among tools, processes, and stakeholders at individual, project, and organizational levels. We believe the outcome of this approach would necessarily position TPCs to develop and shape ethical and audience-focused PM practices through our communication expertise. It also positions TPCs to explain the complexity of PM and the importance of rhetorical communication as central to effective work processes. This change in how we approach PM has clear implications for how we approach instruction and preparation, workplace studies, and best practices of managing people, texts, and projects. Furthermore, grounding PM with a rhetorical approach to communicating also helps TPCs think through the strengths and weaknesses of existing models in productive ways. PM has a direct influence on the frequency and type of communication practices; team dynamics; leadership philosophies; distributed workflows; collaboration activities; and organizational structures, cultures, and philosophies. A rhetorical approach can help make relationships between these activities and agents visible, and demonstrate how associated coordinative communicative dynamics influence the work of project teams. Indeed, this is a natural role for us as TPCs, because advocating for the people around us has always been a foundational mindset of our field.

References

Agile Development. (n.d.) In Technical Communication Body of Knowledge. Retrieved from https://www.tcbok.org/wiki/agile-development/

Allen, J. (1990). The case against defining technical writing. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 4, 68–77.

Ames, A., & Riley, A. Play to your strengths, shore up your weaknesses: The dynamic duo of project manager and strategic information architect. Intercom, 60(8), 25–27.

Amidon, S., & Blythe, S. (2008). Wrestling with Proteus: Tales of communication managers in a changing economy. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 22, 5–37. doi:10.1177/1050651907307698

Anawati, D., & Craig, A. (2006). Behavioral adaptation within cross-cultural virtual teams. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 49, 44–56.

Andersen, R. (2014). Toward a more integrated view of technical communication. Communication Design Quarterly, 2(2), 10–16.

Andersen, R., & Batova, T. (2015). The current state of component content management: An integrative literature review. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 58, 247–270. doi:10.1109/TPC.2016.2516619

Aschwanden, B. (2013, June). Delivering successful projects with global teams. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/e-magazine/international-management/article/delivering-successful-projects-with-global-teams/

Austin, G. (2014). Agile, an awesome alternative. Intercom, 62(10), 14–15.

Baca, S. (2014). The power of technical communication skills in scrum. Intercom, 62(10), 22–24.

Baehr, C. (2015). Complexities in hybridization: Professional identities and relationships in technical communication. Technical Communication, 62(2), 104–117.

Baker, M. (2014). Toward an agile tech comm. Intercom, 62(10), 25–28.

Bartell, A. L., & Brown, K. A. (2009). Secrets to managing a large documentation project virtually-process, technology, and group ethos: Lessons learned. Paper presented at the International Professional Communication Conference. 1–6. doi:10.1109/IPCC.2009.5208723

Batova, T., & Andersen, R. (2016). Introduction to the special Issue: Content strategy—a unifying vision. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59, 2–6.

Beale, M. (2016). Designing an agile game for technical communication classrooms. Paper published in the Proceedings of the 34th ACM International Conference on the Design of Communication, 1-9. doi:10.1145/2987592.2987615

Berggreen, L., & Kampf, C. E. (2015). Project management communication 2.0—the socio-technical design of PM for professional communicators. Paper presented at the International IEEE Professional Communication Conference. doi: 10.1109/IPCC.2015.7235842

Berggreen, L., & Kampf, C. (2016). Stage-gate project management processes as professional communication practice: Connecting technical and marketing communication in new product development. Paper presented at the International IEEE Professional Communication Conference. 1-7. doi:10.1109/IPCC.2016.7740521

Bialek, C. (2008, June). Managing culture change within the context of mergers and acquisitions. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/e-magazine/international-management/browse/3/article/managing-culture-change-within-the-context-of-mergers-and-acquisitions/

Brady, M. A., & Schreiber, J. (2013). Static to dynamic: Professional identity as inventory, invention, and performance in classrooms and workplaces. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22, 343–362.

Brown-Hoekstra, K. (2010, December). How documentation and translation processes affect each other. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/e-magazine/content-strategies/article/how-documentation-and-translation-processes-affect-each-other/

Brown-Hoekstra, K. (2011, December). Integrating localization and technical communication: 10 critical tasks. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/e-magazine/translation-and-localization/article/integrating-localization-and-technical-communication-10-critical-tasks/

Brüggemann, M., & Rehberg, D. (2014, July). Keep the wheels of work turning. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/e-magazine/technical-communication/article/keep-the-wheels-of-work-turning/feed/

Brumberger, E., & Lauer, C. (2015). The evolution of technical communication: An analysis of industry job postings. Technical Communication, 62, 224–243.

Brizee, H. A. (2008). Stasis theory as a strategy for workplace teaming and decision making. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 38, 363–385. doi:10.2190/TW.38.4.d

Burian, A. (2013, February). Managing projects effectively in India. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/e-magazine/international-management/article/managing-projects-effectively-in-india/e-magazine/

Campbell, A. (2007). Managing team projects. Intercom, 54(8), 36–37.

Carliner, S. (2004). What do we manage?: A survey of the management portfolios of large technical communication groups. Technical Communication, 51, 45–67.

Carliner, S. (2012). Using business models to describe technical communication groups. Technical Communication, 59, 124–147.

Carliner, S., Qayyum, A., & Sanchez-Lozano, J. C. (2014). What measures of productivity and effectiveness do technical communication managers track and report? Technical Communication, 61, 147–172.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory (1st ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Clark, D. (2016). Content strategy: An integrative literature review. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59, 7–23. doi:10.1109/TPC.2016.2537080

Collins, J. (2014). Tech docs as agile deliverables. Intercom, 62(10), 10–13.

Codone, S. (2008). The role of the multimedia project manager in a changing online world. The role of the multimedia project manager in a changing online world, 1-5. doi:10.1109/IPCC.2008.4610197

Conklin, J. (2007). From the structure of text to the dynamic of teams: The changing nature of technical communication practice. Technical Communication, 54, 210–231.

Dicks, R. S. (2013). How can technical communicators manage projects? In J. Johnson-Eilola, and S. A. Selber (Eds.), Solving Problems in Technical Communication (pp. 310–332) [Kindle version]. Retrieved from Amazon.com

Dicks, S. (2010). The effects of digital literacy on the nature of technical communication work. In R. Spilka (Ed.), Digital Literacy for Technical Communication: 21st Century Theory and Practice (pp. 51-81). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dicks, S. (2004). Management principles and practices for technical communicators. New York, NY: Longman.

Ding, H., & Ding, X. (2008). Project management, critical praxis, and process-oriented approach to teamwork. Business Communication Quarterly, 71, 456–471. doi:10.1177/1080569908325861

Dubinsky, J. (2015). Products and processes: Transition from “Product Documentation to… Integrated Technical Content.” Technical Communication, 62, 118–134.

Dyer, L. (2012). Information architecture and business process management: A recipe for new business value. Intercom, 59, 16–19.

Fisher, L., & Bennion, L. (2005). Organizational implications of the future development of technical communication: Fostering communities of practice in the workplace. Technical Communication, 52, 277–288.

Flammia, M., Cleary, Y., & Slattery, D. M. (2010). Leadership roles, socioemotional communication strategies, and technology use of Irish and US students in virtual teams. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 53, 89–101.

Fox, A. (2015, April). Building and managing a successful distributed team. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/e-magazine/international-management/article/building-and-managing-a-successful-distributed-team/

Friedl, M., & Worth, C. (2011, July). Project management with scrum. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/e-magazine/international-management/browse/1/article/project-management-with-scrum/

Gallivan, M. J. (2001). Meaning to change: How diverse stakeholders interpret organizational communication about change initiatives. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 44, 243–266. doi:10.1109/47.968107

Getto, G. (2015). Managing experiences: Utilizing user experience design (UX) as an agile methodology for teaching project management. International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development, 7(4), 1–14.

Giammona, B. (2004). The future of technical communication: How innovation, technology, information management, and other forces are shaping the future of the profession. Technical Communication, 51, 349–366.

Goldratt, E. M., & Cox, J. (2014). The goal: A process of ongoing improvement (3rd rev., 20th anniversary ed.). Great Barrington, MA: North River Press.

Gossett, K. (2012). Technical communication and project management. Paper presented at the 30th ACM International Conference on Design of Communication (pp. 371–372). New York, NY: ACM Digital Library. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2379057.2379132

Green, H. M. and DiGiammarino, R. (2014). Project rescue: A mindset for collaboration. Intercom, 61(9), 6–9.

Gonzales, L. (2015). Multimodality, translingualism, and rhetorical genre studies. In Composition Forum, 31. Association of Teachers of Advanced Composition.

Hackos, J.T. (2007). Information development: Managing your documentation projects, portfolio, and people. Indianapolis, IN: Wiley.

Hackos, J. T. (2007). Implementing a content management system. Intercom, 54, 14–17.

Hackos, J. T. (2012). Influencing the bottom line: Using information architecture to effect business success. Intercom, 59(1), 10–13.

Hackos, J.T. (2016). International standards for information development and content management. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 59, 24–36. doi:10.1109/TPC.2016.2527278

Hamilton, R. (2009). Managing writers: A real world guide to managing technical documentation. Laguna Hills, CA: XML Press.

Happ, N. (2014, December). The Asian challenge: Don’t lose face. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/e-magazine/business-culture/article/the-asian-challenge-dont-lose-face/

Harris, B. (2014). Technical authoring skills mat at Red Gate Software. Intercom, 61(3), 6–10.

Hart-Davidson, W., Bernhardt, G., McLeod, M., Rife, M., & Grabill, J. T. (2007). Coming to content management: Inventing infrastructure for organizational knowledge work. Technical Communication Quarterly, 17, 10–34. doi:10.1080/10572250701588608

Hart-Davidson, W. (2015). The turn to learning: A view of UX project management as organizational learning practice. International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development, 7(3), 49–52.

Hart, H., & Conklin, J. (2006). Toward a meaningful model of technical communication. Technical Communication, 53(4), 395–415.

Hartelius, E. J., & Browning, L. D. (2008). The application of rhetorical theory in managerial research: A literature review. Management Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 13–39. doi:10.1177/0893318908318513

Hartwick, J., & Barki, H. (2001). Communication as a dimension of user participation. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 44, 21–36. doi:10.1109/47.911130

Henning, T., & Bemer, A. (2016). Reconsidering power and legitimacy in technical communication: A case for enlarging the definition of technical communicator. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(3), 311-341, doi:10.1177/0047281616639484

Herman, L. (2013). Project manager and the technical communicator: Why it works. Intercom, 60(8), 6–8.

Holdaway, J., Rauch, M., & Flink, L. (2009). Excellent adaptations: Managing projects through changing technologies, teams, and clients. Paper presented at the International IEEE Professional Communication Conference, 1-27. doi:10.1109/IPCC.2009.5208710

Hornik, S., Chen, H., Klein, G., & Jiang, J. J. (2003). Communication skills of IS providers: An expectation gap analysis from three stakeholder perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 46, 17–34. doi:10.1109/TPC.2002.808351

Huettner, B. (2006). Documentation project management resources. Intercom, (53) 18–20, 31.

Jain, J., & Courage, C. (2013). Global design teams: Managing distributed teams effectively. User Experience Magazine, 13(1). Retrieved from http://uxpamagazine.org/global-design-teams/

Jansen, C. (2016, May). Management skills for technical writers. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/rss/article/management-skills-for-technical-writers/

Johnson, R. R. (1997). Audience involved: Toward a participatory model of writing. Computers and Composition, 14, 361–376.

Johnson-Eilola, J. (2005). Datacloud: Toward a new theory of online work. New York, NY: Hampton Press.

Kampf, C.E. (2006). The future of project management in technical communication: Incorporating a communications approach. Paper presented at International Professional Communication Conference. New York, NY: IEEE Xplore. doiI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/IPCC.2006.320372

Kampf, C. E., & Longo, B. (2009). What is excellence for project management knowledge in the context of globalization? Paper presented at International Professional Communication Conference,1-10. doi:10.1109/IPCC.2009.5208707

Kampf, C. E. (2012). Skills and strategies for effective project documentation. In K. Smith and P. Imbrie (Eds.), Teamwork and project management (pp. 226–236). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Kelly, W. (2003). The hidden relationship between project managers and technical writers. Retrieved from Tech Republic: http://www.techrepublic.com/article/the-hidden-relationship-between-project-managers-and-technical-writers/

Kent-Drury, R. (2000). Bridging boundaries, negotiating differences: The nature of leadership in cross-functional proposal-writing groups. Technical Communication, 47, 90–98.

Khoury, S. (2013). Taking Your Seat at the Strategy Table: Three Must-Have Leadership Skills. User Experience Magazine, 13(1). Retrieved from http://uxpamagazine.org/taking-your-seat-at-the-strategy-table/

Killingsworth, M. J., & Jones, B. G. (1989). Division of labor or integrated teams: A crux in the management of technical communication? Technical Communication, 36, 210–221.

Kimball, M. (2015). Training and education: Technical communication managers speak out. Technical Communication, 62, 135–145.

Kimball, M., & Hawkins, A. (2007). Document design: A guide for technical communicators. New York, NY: Bedford-St. Martin’s Press.

Kumar, P., & Salazar, O. (2011, June). Managing expectations across a project lifecycle. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/e-magazine/content-strategies/article/managing-expectations-across-a-project-lifecycle/

Lam, C. (2015). The role of communication and cohesion in reducing social loafing in group projects. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 78, 454–475. doi:10.1177/2329490615596417

Lammers, M., & Tsvetkov, N. (2008, October). More with less: the 80/20 rule of PM. TC World. Retrieved from http://www.tcworld.info/e-magazine/content-strategies/article/more-with-less-the-8020-rule-of-pm/e-magazine/translation-and-localization/

Lanier, C. (2009). Analysis of the skills called for by technical communication employers in recruitment postings. Technical Communication, 50, 51–61.

Lannon, J. (2008). Technical Communication (11th ed.). New York, NY: Longman.

Lauren, B. (2015). Mapping the workspace of a globally distributed “agile” team. International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development, 7(2), 45–62.

Lebson, C. (2012). Making usability a priority: Advocating the value of user research. Intercom, 59(9), 10–13.

Lewis, C. (2012). Leading from the “write.” Intercom, 59(2), 19–21.

Lloyd, S., & Simpson, A. (2005). Project management in multi-disciplinary collaborative research. Proceedings of IEEE International Professional Communications Conference, Limerick, Ireland, July 10 to July 13, 2005, IEEE, pp. 602–611.

Longo, B. (2000). Spurious coin: A history of science, management, and technical writing. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Lund, A. (2011). User experience management: Essential skills for leading effective UX teams. Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Markel, M. Technical Communication (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Mara, A., & Jorgenson, J. (2015). Mutt methods, minimalism, and guiding heuristics for UX project management. International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development, 7(3), 38–48.

Marchwinski, T., & Mandziuk, K. (2000). The technical communicator’s role in initiating cross-functional teams. Technical Communication, 47, 67–76.

Marghitu, D., & van der Zalm, R. (2007). Creating a global team and a global infrastructure. User Experience Magazine, 6(1). Retrieved from http://uxpamagazine.org/global_team_global_infrastructure/

McCarthy, J. E., Grabill, J. T., Hart-Davidson, W., & McLeod, M. (2011). Content management in the workplace: Community, context, and a new way to organize writing. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 25(4), 367- 395.